You are two singers belonging to different generations. Do you, Thomas, think that your start in your career was easier or more difficult than Luca’s?

TH: It was more difficult for him, because the value system has changed. I still worked in a system where most of the intendants of opera houses were as interested in your development as they were in selling their tickets. Today the priority is production, the priority is the success of the opera house, and there are so many young people wanting to sing that the interchangeability of who is on stage is much wider than when I started. Singers who start their career have a much higher pressure of success. Sure, I also had to be successful, but people said: This Thomas Hampson is 32 or 33 and I can see what he will be when he is forty. This kind of measurement does no longer exist. On the other side, the producers have changed. They often come from the theatre and don’t have any understanding of what it means for us to do what they want us to do. We all want to be believable on stage. We all want do to something new, but we have natural laws of singing and physics of our bodies we need to take care of.

LP: There are two main components that are different. Experience is rather a minus than a plus. If you have done a role too often, directors are scared of what you could possibly add to the role. The other thing is that the audience and in general the industry get easily bored about you. José van Dam managed to sing 450 performances of Figaro. Today, nobody can do that. When you have done a role a couple of times, it’s over. People say: What’s next?, because they don’t have the patience to see you growing in a role.

TH: This is true also for me. There are a couple of roles I simply do not get a chance to revisit. This is endemic for the whole industry. Being experienced can have a déjà vu effect. We are in the hands no longer of intendants, but of producers, of people who can create an event. Everything else is secondary. Music is secondary. All is about the success of an event.

And you, Luca? Would you have liked changing your debut from the early 21st Century to the Seventies?

Thomas had certainly the chance to work with conductors and stage directors I would have loved to work with too. I would have adored to work with Bernstein for example or Ponnelle. But, in fact, I cannot complain. I made my debut in Salzburg with Harnoncourt with Thomas as Don Giovanni. I went to every rehearsal in order to absorb as much as I could. And that summer in Salzburg definitely marked my career, marked my way to look at the music. For me it was a privilege to work with Thomas at that moment. A lot of singers do not have such a chance.

Thomas, what would you change if you hat to start a career today?

I would have to be more proactive, to have more contacts, more conversations with intendants and stage directors. But I was as keen as he was in attending rehearsals. When I was in Düsseldorf, I even asked for small roles to be able to have the closest possible look at Wagner operas.

Luca is curious in the same way, but a lot of other singers are not. Many, many do not have this curiosity to absorb everybody’s singing, to learn from people who are on stage. As a young singer I had the chance to sing with people like Ghiaurov, Raimondi, Freni, … this was exciting and certainly good in my biography. But I promise you, I was in every rehearsal to observe these extremely experienced singers taking care of themselves and giving the best of themselves. So, knowing Luca, I consider him as one of the best of his generation in terms of development, seriousness and musicality.

Luca, do you think that you do have also more problems with stage directors who, more and more, seem to forget about the music?

LP: You need to go to the very first rehearsal and forget everything you knew about the piece and listen to the stage director, getting to know what he wants. It’s important to understand what he wants and how he is seeing the character that you have to play and sing. So far, I was lucky and did not have a fight with any stage director. It happened that I had one or the other concern or doubt, but then the stage director was open enough to discuss the matter and to make a compromise. For me it is important to be convinced myself, otherwise it would not be possible for me to convince the audience. The fun part in our job is that, while singing Figaro in 14 different productions, I could find something new in every production. This keeps me going, the possibility to find new colors every time you get back to a role.

TH: Sometimes the staging is startlingly different from what you hear in the music. So many composers get abused today, because there is no real partnership between stage directors, music directors and singers. With all due respect and without becoming a musicologist as Willy Decker accused me one day: there is this phenomenon called harmony. And harmony is not an accident. I believe that, regardless of the event pressure and all this fantastic theatrical things that we enjoy, opera is a musical art form. Every breath I take, is because of the composer and to some extent to the librettist. I think our job is twofold. First of all we need to decode what is given. And this is sometimes difficult for people from the dramatic world, because they are used to creating something out of text and rhythm. We, the singers, do not have that flexibility nor do we need it. There is no greater dramaturge in this world than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. So we must tell the story in the musical language. Pappano once said that the music is not a tomato ketchup or a chutney that you put on the food. The food is the music, and music has a language, it has syntax, it has structure, it has nouns, it has words, and the miracle of music with words is that you really have the dialogue of two art forms in the structure of music. This makes it infinitely theatrical. Yet, for me, opera is not about plot, it is about story, it is not television,

it is not film, it’s not even theater, it’s opera. And to me the absolute center of gravity in any opera is dilemma, the confrontation of major humanistic questions, of motivations and frustrations we have as human beings in whatever epoch we are singing from. And this is as relevant as it was at the time when the opera was written. Does it mean we have to walk around in costumes of that time? Maybe not! But we have to anchor it somehow in the music, which means that Orfeo is different whether you perform the Gluck or the Monteverdi version. But what about toilet seats on the stage when we, on the musical side, are extremely careful to perform the music with as much historical knowledge as we can?

Luca, you often sing buffo roles and you excel in them. Are you a buffo type?

LP: No, not at all. And being fun on stage is much harder than being serious. But even if the situation is fun you need to be serious about it, because if you overdo it, it’s no longer that funny. Given my age, my repertoire has some buffo roles, but I love drama. It’s much more focused and concentrated.

TH: That’s why I like him in Gounod’s Méphisto. He has just the right the voice to do this à la comédie française, lithe an elegant. A number of people think that the role needs a heavy, dark voice. That’s nonsense. Luca’s voice is perfect for this role. People who do the casting often think too much according to clichés. In my career I have certainly pushed the envelope in some repertoire. I am not what you immediately would identify with a Scarpia. I slowly won my place for Simon Boccanegra. But in the beginning some people said: No, his voice is too lyric. Or Macbeth: with my acting and my singing I could convince people and it did not ruin my voice. So maybe we should think about casting and consider alternatives. We could be more adventurous. When Peter Gelb invited Nathalie Dessay as Violetta at the Metropolitan, that was extremely risky, but it was a good experience. Such things are possible if the music is correctly served and if you sing with your voice. Then you will not ruin it.

LP: When Domingo added Otello to his repertoire everybody said: he’s killing himself. Now, 30 years later, he is still singing. I think we should stop thinking about the corps of a voice and focus rather on what an artist can bring to a role. I was incredibly grateful to José van Dam with whom I worked. He told me to sing at the best with my voice, forgetting about what other did in the role. He said: Boris Christoff is unique and you are unique. Be yourself!

But there are a lot of singers who ruin their voice. What’s wrong with them?

TH: Complicated question! It’s correct, careers are shorter. To many singers put themselves under pressure or are seduced under pressure and sing in inadequate ways. The diapason has gone up. We live in a very loud world and in front of the new public going to operas today you feel like a gladiator in the arena. For them, opera is not about the inner meaning. There is a visual excitement in opera, no question, that’s legitimate. But it is not just that. All of us we have to ask the question: what are the physical possibilities of the human being? Do people who listen to a 35 years old voice, care about his future? I’m afraid, we have lost this value. I have read a number of interviews with young singers showing that they do not care about that value. And later they see that their voice is finished much too early. If you are a musician you want to sing until the day you die. If I die, please let me die of a heart attack on stage. I cannot imagine something more wonderful. But to sit around muted because of my musical inabilities, would be terrible. We stay alive because of music.

So, singers suffer from their own attitude of not caring for their voice and they suffer from today’s notion of loudness and sound that has become so exiting with all the amplification. People are used to that loudness and come in the hall in that state of mind. And then, imagine yourself coming from backstage and starting a Winterreise…

LP: I have a suggestion for young singers: never cease to be curious, and listen to the singers of the past. That way you can learn so much. It’s not about copying and stealing ideas, it is about how different voices dealt with different problems. I do not like when young singers stay in their cocoon and say: I do not want to listen to anything. Going to concerts, listening to old and new recordings can help a singer to better understand what he can do with his voice.

What are you doing to take care of your voice besides walking your dogs?

LP: Giving interviews…(both laugh) You need to take care of your entire body. You have to rest. The vocal rest is very important, but the general physical condition is vital too. And very important: never stop to grow as y human being, because the voice is the reflection of what you are as a person. Our job is about communication. You need to have something to say, to be able to say it.

TH: But we haven’t written what we sing. And what some people misunderstand is that, in fact, the success of what we do is how well we have been able to offer everything we are as human beings with our physical abilities, our knowledge and our emotions. Yet we are only at the service of the composer. So, if Luca is successful with some performance, it is because he had everything the composer expected him to have. It’s not about what he thinks about the role or the opera, or what I want to communicate. So, the communication is about what is being recreated. This is our great responsibility. We are recreating artists and this interests me phenomenally. Not all my colleagues are that intellectually engaged, but they have an emotional concept. If they are successful it’s because they can connect with what that person they are singing believes what they believe at that moment. And when they do that, the audience goes up. It is this very treasured moment for people who go to concerts and can say: Something happens to me that is bigger than I can describe. It is a dimension of wonder that we have as human beings. And this is the most important thing about live performances.

—————————–

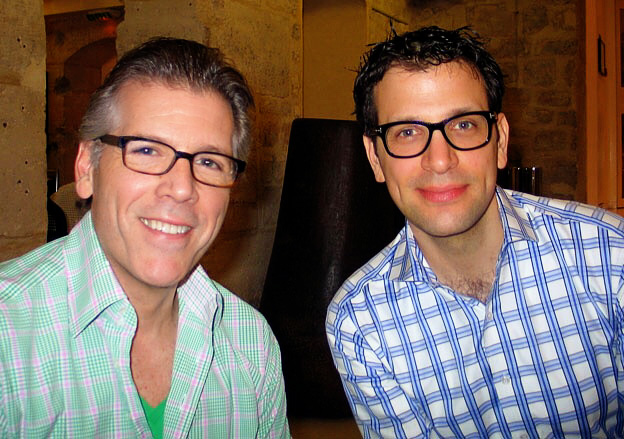

Thomas Hampson

Praised by the New York Times for his “ceaseless curiosity,” Thomas Hampson enjoys a singular international career as an opera singer, recording artist, and “ambassador of song,” maintaining an active interest in research, education, musical outreach, and technology. The American baritone has performed in the world’s most important concert halls and opera houses with many renowned singers, pianists, conductors, and orchestras. One of the most respected, innovative, and sought-after soloists performing today, he was recently inducted to Gramophone’s 2013 “Hall of Fame”; honored as a Metropolitan Opera Guild “Met Mastersinger”; and presented with the first Venetian Heritage Award (2013) and the Concertgebouw Prize (2011).

Internationally recognized for his versatility in operatic repertoire both classical and contemporary, the baritone created the role of Rick Rescorla in the San Francisco Opera’s world premiere production of Christopher Theofanidis’s Heart of a Soldier, which commemorated the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks in 2011. Other important firsts for Hampson in the 2011-12 season included his role debuts as Iago in Otello and in the title role of Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler, both at Zurich Opera, as well as his house role debut as Verdi’s Macbeth at the Metropolitan Opera.

Hampson was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and has won worldwide recognition for thoughtfully researched and creatively constructed programs that explore the rich repertoire of song in a wide range of styles, languages, and periods. Through the Hampsong Foundation (www.hampsongfoundation.org), founded in 2003, he employs the art of song to promote intercultural dialogue and understanding. He is one of the most important interpreters of German Romantic song and with his celebrated “Song of America” project (www.songofamerica.net), a collaboration with the Library of Congress, he has become known as the “Ambassador of American song.”

The singer’s commitment to cross-cultural communication through music and text was showcased in CNN’s “Fusion Journeys” series, for which Hampson was filmed in South Africa in a musical exchange with Ladysmith Black Mambazo. The past season also saw the debut of the “Song of America” radio series, co-produced by the Hampsong Foundation and the WFMT Radio Network of Chicago. Conceived and hosted by the baritone, the series consists of 13 hour-long programs exploring the history of American culture through song, and has aired in more than 250 U.S. markets. A passionate teacher, Hampson will return for master classes to both the Manhattan School of Music’s Distance Learning program and Heidelberger Frühling’s Lied Academy, of which he is the co-founder and artistic director.

Hailing from Spokane, Washington, Hampson has received many honors and awards for his probing artistry and cultural leadership. Comprising more than 150 albums, his discography includes winners of a Grammy Award, five Edison Awards, and the Grand Prix du Disque. He received the 2009 Distinguished Artistic Leadership Award from the Atlantic Council in Washington, DC, and was appointed the New York Philharmonic’s first Artist-in-Residence. In 2010 he was honored with a Living Legend Award by the Library of Congress, where he serves as Special Advisor to the Study and Performance of Music in America. Hampson holds honorary doctorates from Manhattan School of Music, Whitworth College, and San Francisco Conservatory, besides being an honorary member of London’s Royal Academy of Music.He carries the titles of Kammersänger of the Vienna State Opera and Commandeur dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of the Republic of France, and was awarded the Austrian Medal of Honor in Arts and Sciences. In 2011 Hampson was again named ECHO Klassik’s “Singer of the Year,” marking the fourth time he has received that distinction over a 20-year period.

For more information, please visit www.thomashampson.com.

Luca Pisaroni

Italian bass-baritone Luca Pisaroni has established himself as one of the most captivating and versatile singers performing today. Since his debut at age 26 with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festival, led by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Mr. Pisaroni has performed at many of the world’s leading opera houses, concert halls and festivals.

Following a series of critically acclaimed performances of Leporello in Mozart’s Don Giovanni at the Salzburg Festival, Pisaroni begins the 2014/2015 season as Count Almaviva in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro at the Teatro Real in Madrid; a role that he will later perform at the Wiener Staatsoper and the San Francisco Opera. Mr. Pisaroni will also sing the title role in Le nozze di Figaro at the Bayerische Staatsoper in Münich and the Festspielhaus in Baden-Baden this season. He returns to the Metropolitan Opera stage to sing Leporello in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, led by Alan Gilbert, and he performs the role of Enrico VIII in Donizetti’s Anna Bolena at the Opernhaus Zürich and the Wiener Staatsoper.

Concert appearances during the 2014/15 season include Mendelssohn’s Die erste Walpurgisnacht with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s at Carnegie Hall, under the baton of Pablo Heras-Casado, Haydn’s Die Schöpfung with Daniel Harding, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Bach’s B Minor Mass with the Gewandhausorchester and Stravinsky’s Pulcinella with Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony. He will also perform a series of recitals with pianist Wolfram Rieger, at the Muziekgebouw in Amsterdam, Carnegie Hall in New York City and the Vancouver Recital Society.