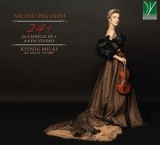

Die Aufnahmen der 24 Capricen für Violine von Niccolo Paganini sind kaum zählbar. Ksenia Milas hat diesen Reigen um vier weitere Etüden erweitert, die erst kürzlich entdeckt und geprüft wurden. Damit weist sie auf durch Covid verpasste Jubiläen hin. Paganini verstarb 1840 und seine Capricen wurden 1820 veröffentlicht.

Milas konzentriert sich in der Aufnahme, nachdem sie die Capricen schon in Recitals aufgeführt hat, darauf, die Musik zum Klingen zu bringen. Die technisch reife Umsetzung ist dabei nur Voraussetzung, nicht das Ziel. Ihr Spiel wirkt überlegender und damit weniger athletisch, als es andere Zyklen dieser Werke vorgeben, ohne dass diese deswegen die musikalische Aussage vergessen würden. Aber Milas geht noch einen Schritt weiter, was sich auch in etwas längeren Spielzeiten niederschlägt. So bringt sie noch eine Spur mehr Deutung und inhaltliche Auseinandersetzung in ihre Interpretation ein.

Dabei belässt sie es hier in der Reihenfolge der Nummerierung und hängt die vier neu hinzugekommenen Stücke hinten an. Mit der letzten Etüde in G-Dur kommt sogar noch eine Tonart ins Spiel, die in den bekannten 24 Werken noch nicht vertreten war, während A- und C-Dur der anderen drei schon Verwendung fanden. Nicht ganz in der Form und im Charakter der Capricen, sind es doch auch reife Werke, deren Erklingen zu begrüßen ist. Und sie bieten noch Neues, wenn etwa die Studie ‘Moderato‘ in A-Dur in die Form einer Solokadenz für ein Konzert mündet.

Erwähnenswert ist noch, dass Milas das gesamte Album in Genua an einem Aufnahmetag auf der Sivori-Geige von Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume aufnahm, die einst Paganini gehörte. Dabei wurde das vom staatlichen Kulturerbe geschützte Instrument von diversen Behörden beaufsichtigt. Außerdem hat sie, so teilt es das Beiheft auch mit, jeweils die erste Einspielung genommen, wie im Konzert, und keine Korrekturaufnahmen.

Recordings of Niccolo Paganini’s 24 Caprices are hard to count. Ksenia Milas’ new recording is special in the sense that she has added four more studies, recently discovered and reviewed. In doing so, she points out anniversaries missed by Covid. Paganini died in 1840 and his caprices were published in 1820.

Milas concentrates in this recording, having already performed the caprices in recitals, on making the music ring. Technically mature performance is only a prerequisite, not the goal. Her playing seems more superior and thus less athletic than other cycles of these works pretend to be, without these therefore forgetting the musical message. But Milas goes one step further, which is also reflected in somewhat longer playing times. Thus, she brings a touch more interpretation and content-related discussion into her interpretation.

She leaves it here in the order of numbering and appends the four newly added pieces at the end. With the last study in G major, even a key comes into play that was not yet represented in the known 24 works, while A and C major of the other three were already used. Not quite in the form and character of the Caprices, these are nevertheless mature works whose performance is to be welcomed. And they still offer something new, for example when the Study ‘Moderato’ in A major leads into the form of a solo cadenza for a concerto.

It is also worth mentioning that Milas recorded the entire album in Genoa in one day on Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume’s Sivori violin, which once belonged to Paganini. In the process, the instrument, protected by the State Cultural Heritage, was supervised by various authorities. In addition, as the booklet informs us, she always took the first recording, as in the concert, and no correction recordings.