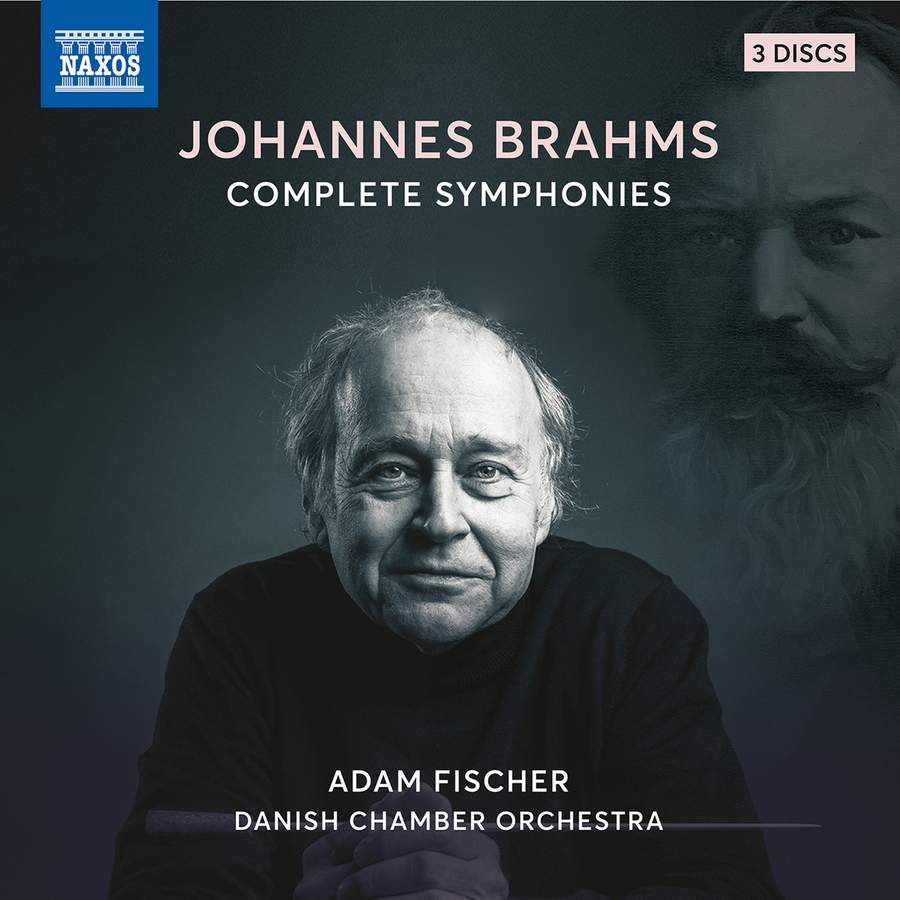

Adam Fischer hat mit dem Danish Chamber Orchestra alle Brahms-Symphonien aufgenommen. Für Überraschungen ist gesorgt.

Mit kräftigem Paukenhämmern charakterisiert Adam Fischer den 1. Satz von Brahms’ Erster Symphonie. Brahms der Wüterich. Scharfe Streicher kontrastieren mit warmem Holz, ehe sich nach diesem grellen Beginn der Satz sehr beschwingt und fast freudig weiter entwickelt, dann wieder nachdenklicher, ehe es dann sehr gestisch, kräftig akzentuiert manchmal ausgesprochen heftig und harsch und immer sehr scharf im Klang weiter geht. Ich kenne kein besseres Wort wie das im Moselfränkischen (i.e. im Luxemburgischen) beheimatete Baupsen, um diesen Satz zu beschreiben. Jeder Versuch, die Musik zu besänftigen will Brahms bei Fischer nicht gelingen. Der hoch dramatische Satz bleibt baupsend, unwirsch, gequält…. Und doch hat jede Klanggeste hier ihre Bedeutung, etwa dieses herrische, hier sehr markante « Genug davon » auf dem Höhepunkt der letzten Steigerung, die alles brutal abbricht, um einen sanfteren, aber keineswegs frohen Epilog einzuleiten.

Im Andante kommt die Musik etwas zur Ruhe, aber im nervösen und drängenden Un poco allegretto e grazioso schlägt Fischer schon das Brennholz, das den Finalsatz befeuern soll, den der Dirigent mit doppeltem Anlauf fast stockend eingeleitet, ehe dann kräftiges Baupsen zur Alphornweise und dem Choral führt. Die letzten 10 Minuten sind wieder heftig und kontrastreich, ja drastisch und beenden eine der dramatischsten Ersten, die ich je gehört habe.

Die Zweite Symphonie ist ihrem Charakter entsprechend viel ruhiger, aber Adam Fischer gelingt es, die Musik mit neuen Farben, ungewöhnlicher Dynamik (und entsprechenden Kontrasten, etwa zu Beginn des 4. Satzes), interessanter Gestik und manchmal kuriosen Tempi zu beleben. Der Finalsatz wird in schnellen, was sage ich, in rasanten achteinhalb Minuten geradezu kaltschnäuzig abgespult. Und so wird diese Zweite bei Fischer längst nicht so pastoral, wonnig oder elegisch wie bei anderen Dirigenten. Aber hatte Brahms nicht selber von einer melancholischen und traurigen Symphonie gesprochen?

Die Dritte hat einen aufgeregt tanzenden ersten Satz, einen unentschlossenen, oft grüblerischen zweiten, mit einigen düsteren und einigen sehr harschen Zwischenrufen. Etwas mehr Ruhe gibt es im Allegretto, wie alle anderen Sätze scharf im Streicherklang, sehr transparent und klar in den Strukturen. Das Finale ist wiederum sehr dramatisch und nervös, mit schneidenden Gesten, melancholisch versonnenen Zwischenspielen.

Markant im ersten Satz der Vierten sind die scharfen, vibratolosen Geigen, die wie Laserlicht dem Rest des Orchesters gegenüberstehen. Ob das das Leuchten ist, das Elisabeth von Hohenberg in der ‘dämmrigen Helle’ der Symphonie entdeckt hatte? Wie auch immer, die Musik fließt kraftvoll mit jenem packenden Zug, den Joseph Joachim schon so sehr in dieser finalwärts gerichteten Symphonie bewunderte. Die klangliche Differenz der hohen Streichern zu den Bläsern bestimmt auch den anmutig schwingenden zweiten, während das Allegro giocoso wie ein Blitz einschlägt und in schnellen 5’39 » energetisch und schnittig zum Finale führt, das ebenfalls mit nur knapp neun Minuten, hier zart und nachdenklich, dort explosiv und leidenschaftlich, Brahms’ symphonisches Schaffen krönt. Der Farbenrausch dieser Interpretation und ihre Energie sind phänomenal. Am bemerkenswerten ist wohl, dass sich bei dabei nirgends Schwere ein stellt, sondern die Musik immer leicht und wie abgehoben klingt.

Und so ist dies sicherlich eine hoch interessante, oft überraschende, immer musikalisch-leidenschaftliche Gesamtaufnahme der Brahms-Symphonien, gewiss nicht die, die ich als eine für den Alltag nehmen würde, aber durchaus mal für besondere Gelegenheiten, für ein besonderes Lustgefühl.

Adam Fischer has recorded all Brahms symphonies with the Danish Chamber Orchestra. Surprises are in store.

Adam Fischer launches the 1st movement of Brahms’ First Symphony with powerful timpani hammering. Brahms the Rage. Sharp strings contrast with warm wood before, after this garish beginning, the movement develops very buoyantly and almost joyfully, then again more reflectively before it continues very gesturally, powerfully accented sometimes decidedly fierce and harsh and always very sharp in sound. I know of no better word than Baupsen, native to Mosel Franconian (i.e. Luxembourgish), to describe this movement. In English the most appropriate translation would be ‘bark’. Any attempt by Brahms to soothe the music does not succeed with Fischer. The highly dramatic movement remains barking, gruff, tormented…. And yet every sound gesture here has its meaning, such as this imperious, here very prominent « Enough of this » at the climax of the final climax, which brutally cuts everything short to usher in a gentler, but by no means joyous epilogue.

In the Andante, the music comes to about rest, but in the nervous and urgent Un poco allegretto e grazioso, Fischer is already chopping the firewood that will fuel the final movement, which the conductor introduces with a double run-up, almost halting, before powerful barking then leads to the Alphornweise and the chorale. The last 10 minutes are again violent and contrasting, even drastic, ending one of the most dramatic Firsts I have ever heard.

The Second Symphony is much quieter in keeping with its character, but Adam Fischer manages to enliven the music with new colors, unusual dynamics (and appropriate contrasts, such as at the beginning of the 4th movement), interesting gestures, and sometimes curious tempos. The final movement is reeled off in quick, what do I say, eight and a half minutes of downright chilling. And so this Second is nowhere near as pastoral, blissful or elegiac with Fischer as it is with other conductors. But hadn’t Brahms himself spoken of a melancholy and sad symphony?

The Third has an excitedly dancing first movement, an indecisive, often brooding second, with some somber and some very harsh interjections. There is a bit more calm in the Allegretto, like all the other movements sharp in string sound, very transparent and clear in textures. The finale is again very dramatic and nervous, with cutting gestures and melancholy pensive interludes.

Striking in the first movement of the Fourth are the sharp vibratoless violins, which stand like laser light against the rest of the orchestra. I wonder if this is the glow that Elisabeth von Hohenberg had detected in the symphony’s ‘dim brightness’? Whatever the case, the music flows powerfully with that gripping drive that Joseph Joachim already admired so much in this finalward symphony. The tonal difference of the high strings to the winds also determines the gracefully swinging second while the Allegro giocoso strikes like lightning, leading energetically and rakishly in a fast 5’39 » to the finale, which also crowns Brahms’ symphonic output with only a scant nine minutes, here tender and reflective, there explosive and passionate. The color palette in this interpretation and the energy are phenomenal. What is most remarkable is that nowhere heaviness does set in, but the music always sounds light and as if it has taken off.

And so this is certainly a highly interesting, often surprising, always musically passionate complete recording of the Brahms symphonies, certainly not the one I would take as one for everyday life, but certainly for special occasions, for a special feeling of pleasure.