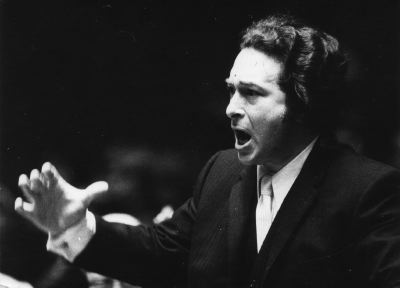

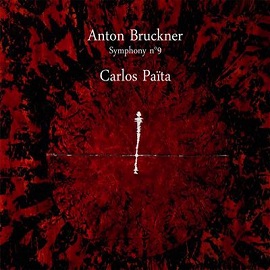

Bruckner’s 9th under Païta is one of the fastest, most dramatic and eccentric on the market. What led the conductor to immerse himself in this music?

AH: It’s true. I was able to see this by consulting my rather extensive collection of interpretations of this work, and I realized the obvious. This rapidity – but I don’t like this word, which means nothing other than what the score in principle demands and which remains formal – deserves rather the qualifier of urgency. On the one hand, there is something hasty, even a decision, that of a confrontation with death, for example, which haunts this work far more than joy. In fact, there is no joy here, which is strange for a confession of faith, since the work is dedicated to « To the good God »)… We perceive only a kind of submission, whereas Païta shows, I think, a form of revolt (we clearly perceive a struggle like that of Jacob with the angel). On the other hand, this defiance and this revolt are related to the meaning of the work, which Païta shifts, even turns with fear, even with panic, very consciously in the musical gesture, towards a metaphysical interrogation in which faith becomes problematic.

What should be praise becomes doubt, suspense, like those first notes of the work, held and restrained.

And then, perhaps the most surprising thing from an aesthetic point of view, one that penetrates deeply into the content of the work, is that our habits when it comes to pathos are those of slowness. The slower, the nobler! And thoughtful. And profound. But Païta overturns this, which is more than a presupposition, more than a prejudice and even a great narrow-mindedness. It’s not a question of listening to a work in terms of what it should be (in the name of what, of what indeterminate norm, of what habits?), but of following what it unfolds and which, as in this case, can be disconcerting, even overwhelming.

Herbert Blomstedt says that the Ninth Symphony is a yearning for eternity, whereas Païta shows us a struggle between life and death. Do you agree?

Herbert Blomstedt says that the Ninth Symphony is a yearning for eternity, whereas Païta shows us a struggle between life and death. Do you agree?

AH: Yes, Herbert Blomstedt understood that, as he often does. However, behind the ‘struggle between life and death’, I see a metaphysical and existential dimension. I mean both a cosmic questioning (there is talk in this work of Creation, it seems to me, of the Glory that eventually presides over it and governs it, but also of nothingness and above all, and this is decisive, of chaos, and therefore of the absence of meaning, which leads us to that existential crisis that Herbert Blomstedt notes.

You know, it’s not a question of folding the work back onto its author and his original intention. Because a great work (and the greater it is, the more it demonstrates this) exceeds its intention. The work is the death of intention. And as a result, dimensions and directions are insinuated into it that indeed exceed its initial purpose. Otherwise, as I said earlier, it’s no longer a work, but a product of dogma (of aesthetic, religious or political principle), in modern marketing terms, a mere label. Many people see works of art through such labels, and to be surprised by them is destabilizing, if not unbearable. You break what is a toy, which was only a peaceful object of entertainment that you will abandon as it is, whereas having heard this concert by Carlos Païta is part of the very carnal depths of existence.

What do you think are the most outstanding features of this interpretation?

AH: Let me try. There are, of course, some great versions of this work in the history of recording. I myself remember Karajan’s in ’66, I think. But fans will also be familiar with Furtwängler’s and Jochum’s, Giulini’s in Chicago, and Barenboim’s three versions, which should not be overlooked, as well as Schuricht’s (very good) and Keilberth’s (remarkable, but forgotten), Celibidache’s, of course, Bernstein’s and Haintink’s first recording, not forgetting Bruno Walter, thanks to whom I discovered the work as a student in financial difficulties (and in any case, at that time there were few versions available, at least to me). There are many other fine interpretations, including Abbado’s last, magnificent one. In this respect, it’s worth noting that the great conductors end their careers with Bruckner, and especially with this 9th symphony (Haitink again, Abbado, Barenboim and others…). It’s a work that stands out in history.

That’s where the fascination comes from, the mystery that Païta renews, as I said. But the most important thing for me is that the work is removed from any purely aesthetic, external appreciation or consideration, if you will. Because it’s not just appropriated, as the great chefs mentioned above have each done in their own way, but with Carlos Païta it’s incorporated, mentally of course, but also physically, I’d say existentially. So much so, in fact, that here the work transcends itself, steps out of itself, as if it were leaving the road in the wake of an event that crosses your path, an accident, in other words, or a tragedy that takes you by surprise. In this way, through this detour, music returns to its primary impulse, its original raison d’être, that of projecting existence in its deepest and highest forms. Aesthetic qualities are of little importance; aesthetics is not art but technique. What counts, however, even if it is unpleasant for the listener, is the interpretive honesty that practices music not to please, but to unfold the great works in their richness, in their different and, above all, unsuspected levels.

This is exactly what Carlos Païta achieves here, having confronted this work and its unique existential complexity and tragedy once and for all, in the same way that we have only one life and our death is our own.

Never before has music gripped us so seriously. We’re not far from the irresistible atmosphere – yes, this is reality – of Dostoyevsky, sometimes of Nietzsche, also of Pascal, and of many others who stared into the void, whether of God or nothingness, of presence or absence.

All we have among Carlos Païta’s recordings are the 8th and 9th. Do you know of any other Bruckner symphonies that he has conducted in concert?

ER: There is a previously unreleased recording of a Bruckner symphony by Carlos Païta. This is the 4th, in which we rediscover the incendiary and fascinatingly committed characteristics that overwhelm the listener. Also a monumental, shattering 6th by Mahler. I’m in contact with his son, Alexandre, to decide on their forthcoming release. This Bruckner 9th celebrates the 10th anniversary of the death of the maestro who left us in 2015 and who was obsessed with this recording throughout his life.