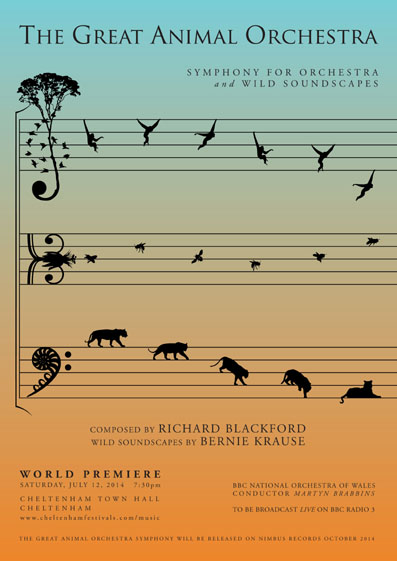

Co-commissioned by the Cheltenham Music Festival and the Aberystwyth Musicfest Richard Blackford’s The Great Animal Orchestra will receive a first performance on July 12th 2014 in Cheltenham Town Hall by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, conducted by Martyn Brabbins. The music is inspired by the work of American environmentalist and soundscape recordist Bernie Krause. This five movement symphony combines live orchestra with Krause’s recordings from around the world – including the Sumatran rainforest, American Pacific tree frogs, African elephants and gorillas, and a range of exotic, South American birds.

This première will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and will be available for a further seven days after broadcast on the BBC iPlayer. Further performances will take place on Saturday 2nd August 2014 at the Aberystwyth Festival and on Monday 4th August 2014 at Birmingham Town Hall with the London School’s Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Richard Blackford.

The companion CD will be available in October 2014 – available on Nimbus Records. The Great Animal Orchestra Symphony will be coupled with a recording of a new orchestration by Richard Blackford of “Carnival of the Animals”.

Here is the composer’s note: In April 2012 I heard extracts from Bernie Krause’s book The Great Animal Orchestra read on BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week. By inventing the term « biophony », or the collective voices generated by all the organisms in a given natural habitat and time, Bernie invites the listener to become aware of the intricate layers of sound created by the animal world within natural habitats which he likens to the layers and textures of an orchestra. When I first visited him in Northern California he not only played the beautiful recordings he had created over forty-five years in the field, ranging from Borneo, Zimbabwe, the Amazon and many other countries, but he also showed me their beautiful and compelling organization on a spectogram, a graphic illustration of sound. Here was a visual impression of the extreme highest « instruments » of the animal orchestra (the bats that are beyond our range of hearing yet visible on the spectogram) to the lowest growls of African elephants. Spectograms also illustrate the varied shapes of animal vocalisations – a swooping glissando, a hard, percussive pattern, a complex, skipping or melodious birdsong – remarkably similar to the notation and design of a musical score. Bernie pointed out the acoustic order (biophony) these collective animal voices generate; that instantaneous and organised expression of insects, reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals in which they inhabit their own set time and frequency niches just as musical instruments operate within a given range in an orchestra. They even interact with each other, interrupting and resuming in the way a concerto soloist interacts with the orchestra. This then is Bernie Krause’s aptly named Great Animal Orchestra in which his unaltered wild soundscape recordings are combined with the resources of a full symphony orchestra.

Here is the composer’s note: In April 2012 I heard extracts from Bernie Krause’s book The Great Animal Orchestra read on BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week. By inventing the term « biophony », or the collective voices generated by all the organisms in a given natural habitat and time, Bernie invites the listener to become aware of the intricate layers of sound created by the animal world within natural habitats which he likens to the layers and textures of an orchestra. When I first visited him in Northern California he not only played the beautiful recordings he had created over forty-five years in the field, ranging from Borneo, Zimbabwe, the Amazon and many other countries, but he also showed me their beautiful and compelling organization on a spectogram, a graphic illustration of sound. Here was a visual impression of the extreme highest « instruments » of the animal orchestra (the bats that are beyond our range of hearing yet visible on the spectogram) to the lowest growls of African elephants. Spectograms also illustrate the varied shapes of animal vocalisations – a swooping glissando, a hard, percussive pattern, a complex, skipping or melodious birdsong – remarkably similar to the notation and design of a musical score. Bernie pointed out the acoustic order (biophony) these collective animal voices generate; that instantaneous and organised expression of insects, reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals in which they inhabit their own set time and frequency niches just as musical instruments operate within a given range in an orchestra. They even interact with each other, interrupting and resuming in the way a concerto soloist interacts with the orchestra. This then is Bernie Krause’s aptly named Great Animal Orchestra in which his unaltered wild soundscape recordings are combined with the resources of a full symphony orchestra.

We started with context. Just as the acoustics of a concert hall or resonant cathedral have a direct bearing on how the music was conceived and is performed, so too are the animal sounds and songs shaped in large part by their habitats and acoustic environments. The rich resonance of a Sumatran tropical rainforest allows the white-handed gibbons to project their joyous duets with a thrilling reverberation, deliberately bouncing their calls off the geographic features of the landscape as well as the humid flora, leaves, branches and trunks of forest vegetation. By contrast, the dry, less reverberant acoustics of the desert works perfectly for the fox or coyote’s bark, whilst the nocturnal ambience of a tropical rainforest provides an ideal setting for polyphonic frog choruses. My first challenge was to create orchestral music whose character would change according to the ambient texture and context of the recordings that surround it.

Leoš Janáček described « the melodic curves of speech » as a key element in his musical thought, and I wondered how orchestral music might be created that derived its melodic curves and rhythms from Bernie’s remarkable recordings. So I set about sketching melodies and rhythms that could become the building blocks of my own orchestral music, layering multiple ostinati figures in the way the Balinese do in their Gamelan music, multiple tempi like Charles Ives, harmonizing, making variations through augmentation and diminution, through intervallic variation and expansion and contraction of musical cells. I wanted my orchestra to be a living organism, with the layers of melody and rhythm audible as a huge ensemble, like Bernie’s wild soundscape recordings, or heard in their constituent parts, like a spotlight on a particular soloist.

To mimic or not to mimic? Animals in the wild – organisms, who vocalise in both competitive and cooperative relationships to one another – often mimic one another’s voices (like katydids, mocking birds, and certain whale species). And from the early stages of evolution we humans have mimicked the vocal and percussive performances of animals, from individual voices to entire organised structures. Examples include the Balinese “ketjak” monkey dance, the instrumental and vocal performances of the Ba’Aka pygmy tribe of Africa, to the incorporation of birdsong into the orchestral works of Messiaen. In The Great Animal Orchestra Symphony I decided to only mimic the astonishing Musician Wren in the fifth movement. Having notated it as a forty four-note song (after which the bird repeats the sequence exactly) I couldn’t resist using it as a basis for a set of variations.