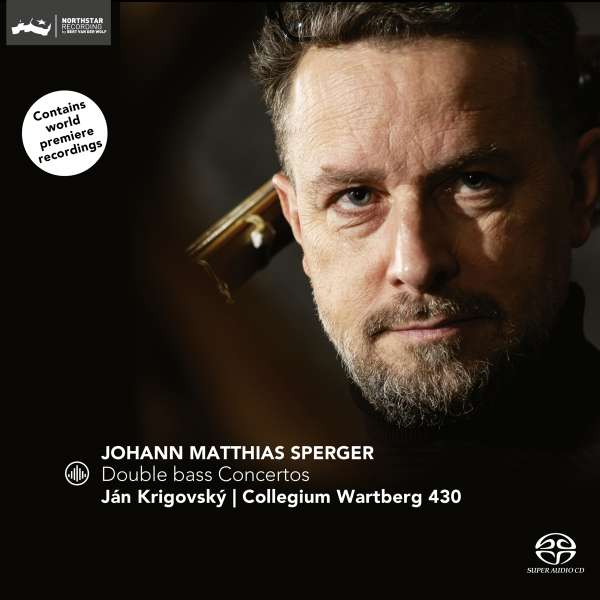

Der Kontrabassist und Komponist Johannes Matthias Sperger hat in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts allein 18 Konzerte für sein Instrument komponiert, die wenig bekannt sind. Das geht soweit, dass das zweite Konzert erst in zweiter und die anderen Konzerte in ersten Einspielungen zu hören sind. Diese Werke sind so elaboriert, dass man an die Cellokonzerte von Haydn denken mag, wenn man sie hört. Dem Kontrabass kommt hier eine erstmals wirklich so zu hörende Sonderrolle zu. Das reicht von technischen Anforderungen wie der Weite des Tonumfangs, Arpeggien und Doppelgriffen bis hin zu dem Reichtum an melodischen Einfällen.

So bieten diese Werke ein reichhaltiges Spielfeld für einen Solisten, der sich auf dieses Abenteuer einlassen möchte. Und das ist in diesem Fall der Slowake Jan Krigovsky. Wobei der Wort einlassen vielleicht einen falschen Eindruck erweckt. Denn er kann auf dem größten Streichinstrument so tänzerisch und elegant spielen wie andere auf den kleineren Vertretern der Streichergattung. Dabei hilft ihm sicher die vom Komponisten erfundene Methode der Daumenlage, mit der sich manche Passagen einfacher spielen lassen. Aber das allein ist es nicht. Krigovsky kann auf dem Bass so elegant wirbeln und flink springen, dass man die scheinbare Plumpheit vergessen muss.

Das Collegium Wartburg bietet dem Solisten die Unterstützung, die für den Orchesterpart erforderlich ist. Auch bei der Ausgestaltung des Ensembleparts hat sich Sperger mit der Harmonik und anderen interessanten Einfällen so manches einfallen lassen. Auch in der Besetzung mit Bläsern, die im dritten Konzert neben den üblichen je zwei Oboen und Hörner vorsieht, sondern auch zwei Trompeten und Pauken, bietet auch diese Seite reizvolle Eindrücke für das Ohr, die das Collegium Wartburg effektiv darbietet.

The double bassist and composer Johannes Matthias Sperger composed 18 concertos for his instrument, which are little known. This goes so far that the second concerto can only be heard in the second recording and the other concertos in first recordings. These works are so elaborate that one might think of Haydn’s cello concertos when hearing them. The double bass has a special role here that can really be heard in this way for the first time. This ranges from technical demands such as the breadth of the range, arpeggios and double stops to the wealth of melodic ideas.

Thus, these works offer a rich playing field for a soloist willing to embark on this adventure. And that is in this case the Slovak Jan Krigovsky. Whereby the word engage might give a wrong impression. For he can play on the largest string instrument as dancelike and elegantly as others on the smaller representatives of the string genre. He is certainly helped by the thumb position method invented by the composer, which makes some passages easier to play. But that alone is not it. Krigovsky can whirl and leap so elegantly on the bass that one has to forget the apparent clumsiness.

The Collegium Wartburg provides the soloist with the support needed for the orchestral part. Sperger has also come up with quite a bit in the arrangement of the ensemble part with the harmonies and other interesting ideas. Also in the instrumentation with wind instruments, which in the third concerto provides not only the usual two oboes and horns each, but also two trumpets and timpani, this part also offers delightful impressions for the ear, which the Collegium Wartburg presents effectively.