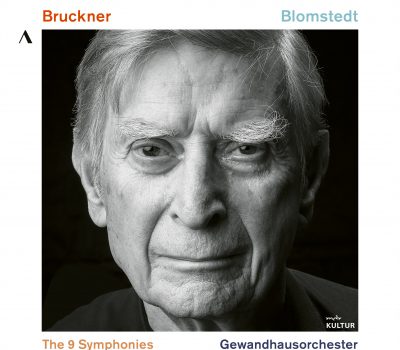

Herbert Blomstedt war der 18. Gewandhaus-Kapellmeister und trat sein Amt 1998 an. Er wurde 2005 von Riccardo Chailly abgelöst, dirigierte aber dennoch immer wieder das Leipziger Orchester. Davon zeugen diese 10 CDs mit den neun Bruckner-Symphonien.

Herbert Blomstedt war 84 Jahre alt, als im Juni 2011 die Erste Symphonie Anton Bruckners dirigierte. Bruckner war, als er das Werk mit über 40 Jahren komponierte wohl keine Jugendlicher mehr, aber er besaß wohl noch viel jugendliche Energie. Und die macht Blomstedt hörbar. Seine Erste ist juvenil und leidenschaftlich, sie ist aber auch durch und durch romantisch, gefühlvoll und klangschwelgerisch. Auffallend sind auch der beschwingt-federnde Charakter des 3. Satzes und die Entschlossenheit des vierten. Eine grandiose Aufnahme! (RF)

Die erst seit 2005 vorliegende Erstfassung der Zweiten, der c-Moll-Symphonie aus dem Jahre 1872 ist es, die Herbert Blomstedt dirigiert. Er tut es ohne Pathos, mit schwungvoller Frische und einem betont leichten Klang. Das Scherzo mitsamt Trio bekommt bei ihm eine ungewöhnliche Eleganz. Das Adagio beeindruckt durch die Natürlichkeit, mit der Blomstedt Bruckners Vorgabe ‘feierlich, etwas bewegt’ umsetzt, nicht ohne mehrmals für zutiefst ergreifende Momente zu sorgen. Die Dramatik des Finalsatzes mit seinen spontanen Eruptionen und seinen ergreifenden Zusammenbrüchen wird selten so packend zum Ausdruck gebracht. (RF)

Keine wirkliche Überraschung bietet die Einspielung von Bruckners 3. Symphonie. Trotzdem ist Blomstedts Interpretation atemberaubend und das Spiel des Orchesters trifft genau die Farben und Stimmungen, die Bruckners Dritte auszeichnen. Spieltechnisch bietet dieses Werk den Musikern sowieso keine Schwierigkeiten, sie bewegen sich auf bekanntem Terrain. Somit verströmt dieser Bruckner eine gewisse Souveränität, ja eine klassische Erhabenheit. Blomstedt, das wissen wir, geht in seiner Auslegung gerne auf den religiösen Hintergrund Bruckners ein und kommt somit den Visionen eines Jochum sehr nahe. Hier präsentiert er die Dritte in der frühen Fassung von 1873. Die erste Fassung wurde durch ihre Wagnerzitate berühmt, die Bruckner quasi als Block eingefügt hatte und die darum ohne Eingriff in die Substanz auf Wunsch entfernt werden konnten.

Es sind Ruhe, Schönheit und Transzendenz, die Blomstedts Interpretation auszeichnen, aber auch das Respektieren und Schärfen der Architektur wird in jedem Falle berücksichtigt. Hier verschmilzt alles zu einem lebendigen Klangkosmos. Bruckners Musik so erklingen zu lassen, in seiner ganzen Pracht und mit seiner klassischen Schönheit, das können heute nur noch sehr wenige Dirigenten. Von der alten Garde Kurt Masur und Bernard Haitink, von der jungen Generation Yannik Nézet-Séguin. (AS)

Im Rahmen seiner Bruckner-Gesamtaufnahme legt Herbert Blomstedt mit der Vierten seine ausgereifte Interpretation in Sachen ‘Romantische’ vor. Erfüllt von innerem Feuer macht die Musik letzten Endes einen erstaunlich ruhigen Eindruck. Kein Zweifel, Blomstedt hat alles unter Kontrolle, Bruckner so gut wie die Musiker des Gewandhauses. Er geht ihm nicht vorrangig um Klangkathedralen, um den großen hymnischen Aufschwung, sondern um Klangvielfalt, ums Detail im symphonischen Ganzen und – vielleicht das Wichtigste – um die romantische Sehnsucht. Die nachdenklichen verträumten Passagen formuliert er besonders eindringlich und er will sie nicht durch aufrauschende Feierlichkeit zerstören. Das gibt der Musik ein ganz singuläres Gesicht.

Die Tonaufnahme ist hervorragend, gut ausbalanciert und im Klang sehr natürlich. (RF)

Die Fünfte dirigiert Blomstedt mit eher breiten Tempi, was die große musikalische Struktur des Werks besonders deutlich werden lässt. Die brillant musizierte Aufführung zeichnet sich durch eine bemerkenswerte Konsistenz aus. (NT)

Bruckners ‘keckste’ Symphonie ist unter ihren neun Schwestern die aparteste. Durchsetzt von Naturlauten, inspiriert von einer Reise in die Alpen lebt sie von der Subtilität ihrer Themen und ihrer Instrumentierung. Diesen besonderen Charakter arbeitet Herbert Blomstedt wunderbar stimmungsvoll heraus. Höhepunkt ist zweifellos der sehr einfühlsam gestaltete langsame Satz.

So gelingt eine in allen Hinsichten schlüssige Interpretation von großer Prägnanz.

Die Tonaufnahme ist sehr präsent, ausgewogen, räumlich und ‘luftig’ (d.h. auch im Fortissimo bei ganzem Orchestereinsatz nie massiv und dicht). (RF)

Es folgt eine außergewöhnlich gute Siebte, sehr schön und einfühlsam gespielt. Herbert Blomstedt nimmt sich Zeit als Wand, aber die Musik bleibt im Fluss und klingt wegen ausgewogener Tempi sehr kohärent. Blomstedt respektiert so vollauf die Architektur der Symphonie. (NT)

Blomstedts Achte Bruckner ist nicht weniger feinfühlig, relativ schlank im Klang und oft zurückhaltend dort, wo andere der Musik mehr Größe geben.

Dabei bleibt die Musik immer ausdrucksstark und würdevoll im ersten Satz, mit ein wenig Angstgefühl, das passt. Das Scherzo ist schnell und kraftvoll, der langsame Satz warm und innig. Das Finale lebt von wechselnden Tempi und viel Kraft.

Das Gewandhaus antwortet auf Blomstedts Dirigat mit einem glühend intensiven Klang. (RF)

Nicht weniger hervorragend ist Blomstedts Aufnahme der Neunten. Das Misterioso des ersten Satzes trifft er genau, ernsthaft und ohne je sentimental zu werden. Aber verinnerlicht ist die Musik durchaus an manchen Stellen, genau wie sie an anderen eine angenehme Wärme ausstrahlt. Das Scherzo ist wirklich lebhaft, ohne Schwere. Ergreifend dann das Adagio mit seinem sehrenden Klagegesang, seinen schmerzlichen Schreien. (RF)

Herbert Blomstedt was the 18th Gewandhaus Kapellmeister, taking office in 1998. He was succeeded by Riccardo Chailly in 2005, but still conducted the Leipzig orchestra time and again. These 10 CDs with the nine Bruckner symphonies bear witness to that.

Herbert Blomstedt was 84 years old when he conducted Anton Bruckner’s First Symphony in June 2011. Bruckner was probably no longer a youth when he composed the work at more than 40 years of age, but he probably still possessed much youthful energy. And Blomstedt makes that audible. His First is juvenile and passionate, but it is also thoroughly romantic, soulful and resonant. Also striking are the buoyant, springy character of the 3rd movement and the determination of the fourth. A grandiose recording! (RF)

Herbert Blomstedt uses the first version of the Second, the C minor Symphony from 1872, a version that has only been available since 2005. He does it without pathos, with swinging freshness and a decidedly light sound. The Scherzo with its Trio takes on an unusual elegance. The Adagio impresses with the naturalness with which Blomstedt implements Bruckner’s specification ‘solemn, somewhat moving’, not without several deeply moving moments. The drama of the final movement, with its spontaneous eruptions and its poignant breakdowns, is rarely expressed so grippingly. (RF]

No real surprise is offered by the recording of Bruckner’s 3rd Symphony. Nevertheless, Blomstedt’s interpretation is breathtaking, and the orchestra’s playing captures precisely the colors and moods that distinguish Bruckner’s Third. In terms of playing technique, this work offers the musicians no difficulties anyway; they move on familiar terrain. Thus, this Bruckner exudes a certain sovereignty, even a classical grandeur. Blomstedt, we know, likes to go into Bruckner’s religious background in his interpretation and thus comes very close to the visions of a Jochum. Here he presents the Third in the early version of 1873. The first version became famous for its Wagner quotations, which Bruckner had inserted as a block, as it were, and which could therefore be removed if desired without interfering with the substance.

It is tranquility, beauty and transcendence that distinguish Blomstedt’s interpretation, but respect for and sharpening of the architecture is also taken into account in every case. Here everything merges into a living cosmos of sound. To let Bruckner’s music resound like this, in all its splendor and classical beauty, is something that very few conductors can do today. From the old guard Kurt Masur and Bernard Haitink, from the young generation Yannik Nézet-Séguin. (AS)

In the context of his complete Bruckner recording Herbert Blomstedt presents with the Fourth his mature interpretation in the matter of this romantic symphony. Filled with inner fire, the music ultimately makes an astonishingly calm impression. No doubt, Blomstedt has everything under control, Bruckner as well as the musicians of the Gewandhaus. He is not primarily concerned with cathedrals of sound, with the great hymnal upsurge, but with variety of sound, with detail in the symphonic whole, and – perhaps most important – with romantic longing. He formulates the pensive, dreamy passages with particular urgency, and he does not want to destroy them with roaring solemnity. This gives the music a very singular face.

The sound recording is excellent, well balanced and very natural in sound. (RF)

Blomstedt conducts the Fifth at rather broad tempos, which makes the work’s large musical structure especially clear. The brilliantly performed performance is distinguished by remarkable consistency. (NT)

Bruckner’s ‘perky’ symphony is the most distinctive among its nine sisters. Interspersed with sounds of nature, inspired by a trip to the Alps, it thrives on the subtlety of its themes and instrumentation. Herbert Blomstedt brings out this special character wonderfully atmospherically. The highlight is undoubtedly the very sensitive slow movement.

Thus, a coherent interpretation of great conciseness succeeds in all respects.

The sound recording is very present, balanced, spacious and ‘airy’ (i.e. never massive and dense even in fortissimo with full orchestra). (RF)

An exceptionally good Seventh follows, beautifully and sensitively played. Herbert Blomstedt takes his time as Wand, but the music remains in flow and sounds very coherent because of balanced tempi. Blomstedt thus fully respects the symphony’s architecture. (NT)

Blomstedt’s Eighth Bruckner is no less sensitive, relatively slender in sound and often restrained where others give the music more grandeur.

Yet the music always remains expressive and dignified in the first movement, with a bit of angst that fits. The scherzo is fast and powerful, the slow movement warm and heartfelt. The finale thrives on shifting tempos and plenty of power.

The Gewandhaus responds to Blomstedt’s conducting with a glowingly intense sound. (RF)

Blomstedt’s recording of the Ninth is no less outstanding. He captures the first movement’s misterioso precisely, earnestly, and without ever becoming sentimental. But the music is definitely internalized in places, just as it radiates a pleasant warmth in others. The Scherzo is really lively, without heaviness. Then the Adagio is moving with its very lament, its painful cries. (RF)