Mr. Giltburg, how did the decision come about to present a complete recording of all Beethoven piano sonatas for the Beethoven Year?

Good day! I think that Beethoven’s 250th anniversary itself was the main catalyst. I still remember the moment I first thought about the project; I was in South Korea in early 2019, pacing around my hotel room, and all of a sudden some kind of switch flipped in my mind, and my world changed from one in which there was no way I would have played all the sonatas ever, to a world in which it was 100% certain that I would (I don’t have an explanation for the switch flip…!). And then, with the anniversary looming, it seemed the most obvious thing in the world to do it in 2020, which also meant it became a one-year project. The (immense) challenge was very appealing, but much more than that I remember the excitement of being about to discover all the sonatas I had not played by that point.

You say you had never rehearsed a large part of the sonatas and played them in public before the recording project. Apparently, you rehearsed the sonatas in a very short time and then also filmed them very quickly one after the other. Do you see a major difference between having a lot of time to rehearse a piece and having very little time?

I certainly see a difference between playing a piece you have recently learned and performing a piece you have learned years ago. I think that with most pieces we play, there’s a series of stages we pass through – the initial excitement of discovering a piece and falling in love with it; then the exploration of the work and the discovery of more and more details and layers in it; finally bringing those details and layers together to form an interpretation of the piece you could present to the audience, and fine-tuning this interpretation through a series of performances. This is one ‘cycle’ of preparation, which is then repeated, in miniature, every time you come back to a piece in later years – you yourself will have changed, and so will your view of any piece of music you play.

A layperson often imagines that a musical work of art must first ‘mature’ for a while inside an artist who rehearses it – like a good wine, so to speak – before it is ‘ripe’ for performance. Is that a wrong perception?

It is neither right nor wrong, just that you would most likely end up with two different interpretations. What I mentioned above, the repeated cycles of approaching the same piece over many years, they cannot be compressed – you can’t simulate them without the actual passage of time. But the first cycle – discovery, exploration and forming an interpretation – can be short or long, expanded or condensed. Condensed can be more challenging, but also more thrilling – you are still in the throes of the initial feeling of falling in love, burning with excitement about the music. It’s a powerful feeling, and in my opinion valuable in itself. I’m absolutely sure that my interpretation of the sonatas will change over the years, but I’m also immensely happy to have had that year of intense exploration of Beethoven’s music and to have been able to share it with an audience.

Why did you decide to present the sonatas primarily as videos/short films?

I should perhaps explain that the project was initially conceived purely for YouTube, and had therefore to be visual. I had by that time worked multiple times with Stewart French, the filmmaker behind ‘Fly On The Wall’, whose approach I love – full-movement takes, single camera, trying to capture the spirit of a ‘live’ performance. I thought his style would work really well with the kind of project I was thinking of, so I approached him and was really happy that he was interested in doing this together. It was only later in the planning that Apple Music told us they wanted the videos for their platform, and the audio albums came last of all, after the first videos had already been released.

It is remarkable in this day and age that you played all the sonatas live in the studio, in long takes, in the videos completely unedited, in the album versions only with very few corrections. Did you also want to make a statement against today’s studio habit, in which complex classical works are often recorded in many small takes and then only really become a proper ‘recordingn the editing room?

Not at all! As I mentioned above, this way of recording was simply the result of Stewart’s method of filming. In my opinion, it is neither better nor worse than the classic way of recording in a studio, which I also love. In a way, what we did is a kind of hybrid between live performances and studio recordings: we did record full-movement takes with minimal corrections, but I was also able to play the same movement multiple times to get a result I was happy with. Again, neither better nor worse, just a different approach.

Why did you choose Fazioli?

My relationship with Fazioli goes a long way back; I first played on a Fazioli in 2011, and since then, whenever I have the chance, I prefer to play on one of their instruments. All of my solo albums since 2017 have, too, been recorded on a Fazioli piano. For me, the best Faziolis are simply outstanding; they have an action so light and precise it seems to react immediately to any small change of tone or color, combined with amazing clarity and a beautiful singing tone.

In the meantime, there are many renowned pianists who are no longer satisfied with the standard Steinway D sound and are looking for alternative tones from companies such as Fazioli, Bösendorfer or also Shigeru Kawai. Are the days of Steinway supremacy numbered? And if so, what might be the reason?

I wouldn’t be so sure! Rather, what I think is happening is that we are lucky to have an increasing variety of different piano sounds and actions you can choose from as a pianist. So it becomes a matter of personal preference, rather than superiority of one brand or another.

Some of your recordings in Sacile near Venice took place in the midst of Corona crisis, when Italy in particular was badly affected and in complete lockdown for many weeks. Can you give us an insight into the problems this led to in the implementation of the project?

Sure – by the time the lockdowns started in March 2020, we had filmed 11 sonatas, about 1/3 of the project. After March, we had no idea if and when we’d be able to continue the filming at all. In theory, those months at home would have been a great opportunity to learn all remaining new sonatas, but at those highly uncertain times, I found that my desire to explore new musical worlds had completely evaporated! I wanted ‘comfort food’ – music I knew well, often going back to pieces which I haven’t played since I was a teenager. It was only in the summer, when there was a glimpse of hope of continuing the filming in July, that the project restarted. We had no idea what the autumn would bring, so we decided to go all-in – to film as many sonatas as we could in one go. So we filmed 13 sonatas in July, in just 9 days; we called it our ‘Beethoven summer madness’… And then the remaining 8 sonatas were filmed in two batches, in September and November, again during dips in the pandemic waves. So, from March 2020 onwards, the project became inseparable from the pandemic; the lockdowns effectively dictating our filming schedule. By the end of November, having finished the last sonata, I felt nothing but immense gratitude at having been able to complete the project, despite the Covid-19 situation.

Especially during the Corona period, you developed as an artist spending a lot of time on the internet with streaming concerts. You practically made music from your own living room, performed pieces as well as giving virtual master classes. According to my perception there were two ‘parties’ in particular among the well-known artists during the Corona crisis: one took the standpoint: « I’m not giving away my interpretation, my source of income, for free. Whoever wants to hear me should please pay me a fee, also for streaming events. » The other party, which apparently included you, saw the crisis as an opportunity to tap into a whole new target group and maximize their follower numbers on social media portals with free streaming concerts and free master classes. Looking back, how do you see the developments? Do you have any understanding for those who say: « No matter what happens: I don’t play in public without a fee as a matter of principle”?

At the time, the question of money or fees never entered the equation… nor were the streams done with the explicit purpose of getting a larger social media following. Rather, there was a dire inner necessity for me to keep playing, and those streams were the only way for me to do it. Looking back, I mostly see the live-streams as a way of coping mentally with a highly stressful and uncertain situation. Those streams gave me focus and structure at a time when one concert after another was getting cancelled, and the future looked totally obscure. I also quickly realized that it was really difficult for me to practice without a clear goal, so those streams gave me something to work towards on a daily basis – I knew I had to be online 2-3 times a week and play 30 minutes of music, no matter what. Moreover, the relationship which then started developing with the online audience became a huge source of mental support in itself. Social media allows you to have a direct contact with the audience, and their immediate feedback and encouragement meant the world to me, especially when someone would write that my streams were helping them in any way. However, all of this is such a personal thing; we were each coping with the situation differently and I have full understanding for all of my colleagues.

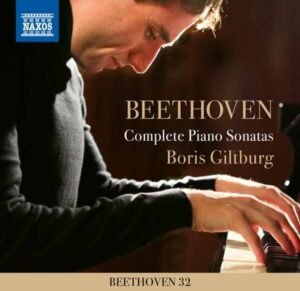

With your label Naxos, you released the Beethoven sonatas on CD only as a box set. The individual albums were only available as downloads or streams. Is the time of collectors over who gradually put such a cycle on their shelves as single CDs?

With your label Naxos, you released the Beethoven sonatas on CD only as a box set. The individual albums were only available as downloads or streams. Is the time of collectors over who gradually put such a cycle on their shelves as single CDs?

As I mentioned above, this cycle is perhaps not typical of a regular recording project. It was planned as a video cycle, and the idea to release the audio albums came only later. That’s why the physical albums (which we didn’t plan of releasing at all at first) came last of all, when it made more sense to release them as a box.

After you won Brussel’s Concours Reine Elizabeth, one of the most prestigious competitions in the music world, probably all doors were open to you. I suspect several labels will have been clamoring to work with you. You obviously made a conscious decision to cooperate with Naxos, which surprised many observers, because to this day Naxos is considered more of a repertoire label than an artists’ label. Why did you choose to go with Naxos?

Naxos gave me almost complete liberty in choosing the repertoire to record, which is invaluable for me. They also strongly support me on releasing multiple albums a year, and their preference for complete cycles coincides with own my tendency of exploring every corner of a beloved composer’s output. It’s been a very fruitful collaboration, and I’m looking forward to our future releases!