Unter den vorhandenen Fertigstellungen von Schuberts unvollendeter Sonate D 840 ist die von Ernst Krenek die erfolgreichste. Es ist auch die, welche Can Cakmur in dieser Aufnahme benutzt, die für mich zu einer kompletten Wiederentdeckung dieser Sonate führte.

Cakmurs Phrasierungen und sein Spiel mit Dynamik und Farben sind überwältigend. Die extreme Klarheit, die Phasen von Entspannung und Anspannung, die unglaublichen Nuancen, die das Spiel bereichern und es so unmittelbar rhetorisch werden lassen, zeigen welchen Grad an Eindringung in Schuberts Welt der junge türkische Pianist hier erreicht, wie er die Gefühle meistert und sich zu eigen macht, ob im Liedhaften oder in der nervös-fiebrigen Erregung. Da verblassen die Interpretation von Brendel und Badura-Skoda zu aufgedunsenen Nichtigkeiten. Nur Richter kann noch mithalten, obwohl seine spannende Interpretation mit der von Cakmur nichts gemein hat.

Im Andante bringt dessen besinnliches, sehr liedhaftes und poetisches oder auch sehr bestimmt formuliertes Spiel den Satz bestens zur Geltung. Das von Krenek vervollständigte Menuett wird reich diversifiziert und kontrastiert und so total aufregend.

Im letzten Satz strömt die Musik drängend und ohne jede Spur von Schwere und Pathos dem Schluss entgegen, jene von Brendel und manchmal sogar von Richter als bedeutsam angesehene Schwere, die bei Cakmur durch Frische, flinke Leichtigkeit und Licht ersetzt wird. Ich kenne keine Aufnahme, in der die Novität der D 840 so evident wird wie in dieser hier.

Nicht weniger überzeugend und aus dem Innersten heraus empfunden spielt Cakmur das Allegretto c-Moll D. 915, sowie die tänzerische Ungarische Melodie D 817.

Cakmur eröffnet sein Programm mit der Zweiten Sonate von Ernst Krenek. Das Allegretto gestaltet er ebenfalls sehr rhetorisch. Der zweite Satz ist ein Marsch mit einem Trio. Cakmur spielt ihn ungemein spontan und kommunikativ und diese geniale Beherrschung der Materie gibt dem Finale Allegro giocoso eine Ironie und ein Mokieren, welche die Sonate brillant beenden.

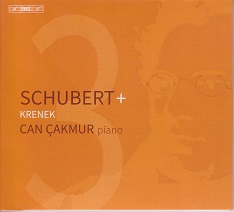

Of the existing completions of Schubert’s unfinished Sonata D 840, Ernst Krenek’s is the most successful. It is also the one that Can Cakmur uses in this recording, which led to a complete rediscovery of this sonata for me.

Cakmur’s phrasing and his play with dynamics and colors are overwhelming. The extreme clarity, the phases of relaxation and tension, the incredible nuances that enrich the playing and make it so immediately rhetorical, show how deeply the young Turkish pianist penetrates into Schubert’s world, how he masters the emotions and makes them his own, whether in the songlike or in the nervous, feverish excitement. Brendel’s and Badura-Skoda’s interpretations pale into bloated nothingness. Only Richter can keep up, although his exciting interpretation has nothing in common with Cakmur’s.

In the Andante, his contemplative, very songlike and poetic or even very determinedly formulated playing brings out the best in the movement. The minuet, completed by Krenek, is rich in variety and contrast, and thus totally exciting.

In the last movement, the music flows to the end with urgency and without any trace of heaviness or pathos, that heaviness which Brendel and sometimes even Richter consider significant and which Cakmur replaces with freshness, nimble lightness and ease. I know of no recording in which the newness of the D 840 is as evident as in this one.

Cakmur’s performance of the Allegretto in C minor D 915 and the dance-like Hungarian Melody D 817 is no less convincing and deeply felt.

Cakmur opens his program with Ernst Krenek’s Second Sonata. The Allegretto is also very rhetorical. The second movement is a trio march. Cakmur plays it with great spontaneity and communication, and this brilliant mastery of the material gives the Allegro giocoso finale an irony and mockery that brings the sonata to a brilliant close.