What are your favorite memories with your father?

There are so many! On the other hand, some are still very close to my heart. At a concert in London’s Festival Hall with the Royal Philharmonic, he conducted excerpts from Carmen, the Grieg Concerto and Saint-Saëns’s Third Symphony to a full house – some people couldn’t get in and could hear the music behind the curtains. This audience had given my father what few others had.

I remember very well that during a concert at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, my sister and I decided to go for a drink at the little bistro across the street just before the concert. Some of the musicians in the orchestra were having a little drink. I asked one of the violinists: « Why are you having a little drink? His answer: « …we need it for the honor of giving all our hearts to your father… ». Or, after a concert of Bruckner’s Seventh, I can still see my father stepping down from the podium, embracing me in an indescribable state of perspiration, and saying, « Alexander, I was in Walhalla! »

A very important memory dates back to 2015, just before he died. I was supposed to play the role of Beethoven in the theater, which I finally did in December 2023. When I announced this then to my father, I heard him say, « Who better than you to play the role of Beethoven? » And he added, « …knowing Beethoven as well as we do…. Not only the composer, but also the man and his sufferings, all that he tells us behind his notes, because we have experienced these things in our own way ».

What was the most important lesson he taught you?

My father and I were often together and shared intense moments about art in general. Everything he said to me, or the images I keep of his music, is just nourishment for me and for the theater I practice. In addition, he left me the musical genes (although I’m not a musician myself), but above all the ear. You can’t imagine that it’s a gift from God to have that, but it’s also a pain. To give a phrasing of the text with the power of sounds that are transformed into your own, syllables that give the impression of the sounds of instruments, melodies of your own music, especially my father’s. For my father, the notes of a score are the words of a play.

Your father was admired by some, and criticized by others. How did he live with this dualism of reactions to his artistic activity?

My father was a free man, and he didn’t care what others thought. He was not afraid of the emotional approach to things or of anyone. He gave himself completely to his music, which reflected his own life. Harry Halbreich told me about Coriolan: « His interpretation of Coriolan is your father, with all the intensity with which he lived his passion, his pain… ».

I remember touring with the PSO in 81-82 with Bruckner’s Eighth in Toulouse, Geneva, Paris and London. The greatest success was in London. At the height of the Falklands War, an English orchestra was playing under an Argentine conductor!

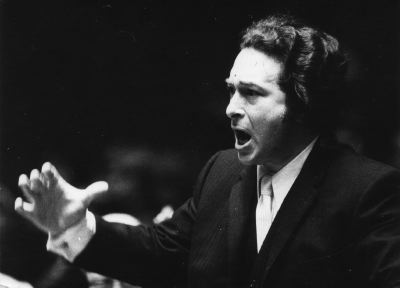

On March 7, 1968, I was deeply impressed by your father during a concert with the Orchestre symphonique de RTL in Luxembourg, performing works by Tchaikovsky, Villa-Lobos and Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra. My memories are of a conductor who valued precision as much as intensity. Are these the dominant characteristics of your father’s art?

Yes, if you’re not precise, you’ll never be able to render these musical tableaux. But in addition to intensity, there was also the beauty of sound, the cohesion of all the instruments, the sensitivity of the strings or the power of the brass.

Like Karajan, your father was very interested in recording and wanted to keep everything in his hands. He had his own ideas about how to achieve the sound he wanted, and he supervised the mixing and mastering himself. Do the two performances, Shostakovich and Bruckner, reflect his ideas about recording?

It is no coincidence that in 1969 he signed a contract with Decca for high-fidelity recordings on Decca Phase 4, which eight years later gave birth to digital recording. In 1978, with the release of Pathétique, Païta was one of the first to work with digital sound. He needed this power because he felt it reflected his music well. If you watch a clip of the rehearsal recording of Beethoven’s Fifth on YouTube, you’ll see how true that is. He bought the microphones himself and ordered the Wagner tubas for his orchestra. He almost always doubled certain instruments, strings, horns, tubas, etc., to get the sound he felt he wanted… which, of course, drove the producers crazy.

How do these recordings affect you when you listen to them today?

How do these recordings affect you when you listen to them today?

I still listen to my father’s music, and I must admit that it inspires me not only in my work in the theater, but also as a man. Just yesterday I listened to his Bruckner Eighth, whose interpretation perfectly reflects the sound he intended. When I hear the final crescendo of the 4th movement, I feel like a Viking warrior whose body is burning on a lake, returning to Walhalla in the mist! This sublime grandeur accompanies me every day in my personal life. And as we say in Argentina, Gracias Viejo!

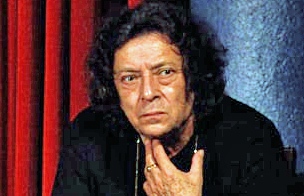

Carlos Païta: Höchste Intensität für Shostakovich und Bruckner