What does this award mean to you and how do you feel about receiving it?

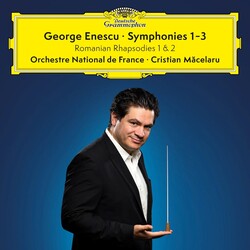

I am, above all, very happy for the opportunity to produce this album with Enescu’s music. This is music I have loved all my life and I have always wanted to bring it into a brighter spotlight by recording the three symphonies and the two rhapsodies. These recordings are just the beginning, so to speak, of my broader vision for showcasing Enescu’s music. I am delighted that these efforts continue to garner such attention. For me, this award is a recognition of not just our hard work, but also the incredible quality of Enescu’s compositions, which fills me with great joy.

I am incredibly happy with how the effort we have put into this project is being acknowledged and understood and how this gift I wish to share with the world through these recordings is being received. It is such a wonderful thing. Of course, I am profoundly grateful for the honor that this award represents it is something very beautiful.

What other international reactions to this album have you noticed?

I have received responses and feedback from people all over the world. Additionally, I was honored in France with the Album of the Year award at the Choc Awards, along with the Diapason d’Or for Album of the Year. This recording has captured worldwide interest. I hear a lot about Enescu’s music, and many are experiencing it for the first time. This is the real reason behind these recordings – to present to the world the beauty of a music that has not been outside Romania for the last 100 years. I would even say that, outside of Europe, there has not been much emphasis placed on what Enescu created, apart from the First Rhapsody. For me, his symphonies – the mature works I’ve recorded – hold phenomenal importance in the history of music and possess extraordinary beauty.

I’d like us to take a brief look at the history behind the creation of this album. When did the idea to record Enescu’s works first arise, and how did it lead to the collaboration with Deutsche Grammophon?

It all started during the negotiations for my appointment as the musical director of the Orchestre National de France in 2019. During the negotiations, I expressed that one of my main desires was to take on this major challenge together with the orchestra, as it would require a significant effort from both sides. I told them that I would accept the role only under the condition that we would embark on this project together. We discussed a long-term vision spanning several years, where I aspired to collaborate with Deutsche Grammophon and the Orchestre National de France to create these recordings that would serve as a legacy of our collective work, but also, more importantly, of Enescu’s music. I truly believe that it’s essential for his music to be performed by a French orchestra that understands his unique style.

So, in 2019, we began the discussions and then we reached out to Deutsche Grammophon. We managed to convince them since they had not previously included Enescu’s music in their catalog. Everything fell into place beautifully, and by 2021, we started recording. Once we had the green light to begin, I also initiated talks with the George Enescu Museum and the Romanian Ministry of Culture to gain access to the manuscripts. This allowed me to correct the countless errors- if I may call them that – in the scores and produce a recording that would be as close as possible to what Enescu himself envisioned.

Just to clarify, you took the manuscripts from the Enescu Museum and rewrote them, putting them into a form that could eventually be published later, correct?

Just to clarify, you took the manuscripts from the Enescu Museum and rewrote them, putting them into a form that could eventually be published later, correct?

Exactly. I took the manuscripts in collaboration with the Romanian publishing house Grafoart and we reviewed them together. They helped me ensure that everything that needed correcting was addressed because Enescu’s music was published only once. This is challenging because there are many potential mistakes, especially in a publication from almost 100 years ago, when attention to detail was not as precise. Typically, composers go through second, third, or even fourth editions to fix many issues, but that did not happen with Enescu. That is why it was so important for me to go back to his manuscripts, which are incredibly clear and perfect. There is no reason for any mistakes to be present. Together, we corrected everything and new scores were made to ensure everything was clear and well laid out, so it could be easily read. Many of Enescu’s scores were still handwritten and, over time, these manuscripts had been copied and recopied, passing through many hands, which contributed to the wear and tear. But I believe the effort I invested, along with Grafoart’s support, has paid off. I hope that future performers of Enescu’s music will now have a more up-to-date and improved version.

You have done a real musicological detective job. I believe this is a gift, especially in 2025, when we mark 70 years since Enescu’s passing, making his music more accessible through scores that can be shared with more musicians, particularly those from abroad. This has generally been an issue when it comes to making Enescu’s music accessible. When can we expect the publication of these new scores?

All I can say about this is that the people who have the materials and are handling this process will make the decision. I cannot give a precise date, but yes, the idea was to promote Enescu’s music in a way that facilitates its performance. Because, indeed, many are familiar with Enescu’s works, but I often encounter situations where people wish to perform his music, only to find that the scores either don’t exist or are of inferior quality – difficult to read and not at the same standard as the scores of composers who are frequently performed. That is why I suggested making it easier for everyone to perform Enescu’s music. Now, I believe we are finally at the last step toward achieving that.

I would like to ask you about the distinctiveness of the Orchestre National de France, which plays a central role in these recordings, alongside you. Why is it necessary for Enescu’s music to be performed by a French orchestra or do you think it would be better for it to be performed by one, given the specifics of Enescu’s scores that you have mentioned?

First, for those who might not know, Enescu was trained and studied in Paris in his later years. He was deeply influenced by the discoveries he made there, the teachers, the friends he made and the collaborators he worked with daily. Because of this, everything written in Enescu’s scores, even in the rhapsodies, is in French. All the instructions on nuances, interpretation, and articulation, all those subtle aspects of the music are provided in French. But they are not just conveyed in this language; they are instructions that are very much tied to the French musical tradition. Just as German-speaking composers have their own distinct language, so do French composers. For comparison, if we look at Gustav Mahler’s music, who lived at the same time as Enescu, Mahler would write these instructions in German. But these indications cannot be perfectly translated into another language because they express nuances and meanings that reflect his desire for the music to be played in a particular way. Similarly, Enescu wrote these musical instructions in French.

At the same time, the musical gestures that Enescu writes are very characteristic of French music. You should know that almost every note in his symphonies has an indication of how it should be played. Enescu uses accents, dots, lines, commas, legato markings and portato indications. One particularly beautiful thing he invented – no other composer uses this terminology – is parlando-rubato, meaning sung in a way as if speaking. This refers to the folk singing style. He includes this notation in his scores, crafting a way to express parlando-rubato.

It seems to me that Enescu was trying to capture the music he heard around him and the way it was being played because a French orchestra produces sound quite differently from a German orchestra. A French orchestra has a much lighter sound compared to the German one, which tends to have a deeper, heavier, and smoother tone, full of life. On the other hand, a French orchestra typically has a more transparent, elegant, and lighter sound. That is why Enescu tried to capture these qualities in his compositions. When you place these instructions in front of an orchestra whose tradition is to perform without relying on such indications, they will understand the music more immediately, easily, and directly. Because of this, I was so eager to collaborate with a French orchestra. After all, the tradition of the French orchestra, based in Paris and made up of musicians who went through the same school as Enescu, at the Paris National Superior Conservatory, allows these musicians to carry on the tradition Enescu encountered in Paris and tried to capture in his scores. For this reason, I believe a French orchestra, like the Orchestre National de France, which, by the way, has built a career by preserving this old tradition of performance, is the best fit to interpret Enescu’s music.

ICMA winner Cristian Măcelaru: « It was important for me to go back to Enescu’s manuscripts »

Cristian Macelaru

(c) WDR-Thomas Brill

What was the orchestra’s reaction to Enescu’s music?

Whenever we perform Enescu’s music – especially his symphonies, not just the well-known and beloved First Rhapsody, but his other works – whenever I introduce this music to an orchestra that has never played it before, the musicians are initially somewhat intimidated, because Enescu’s music is very complex. But after rehearsing it for a couple of days, they managed to play it and understand it. Every single time, the musicians come to me and say they have discovered an extraordinary world they did not even know existed. I have yet to hear anyone say they did not enjoy playing an Enescu symphony. Every time, the response is the same: ‘Wow, that was incredible! This music is absolutely amazing! It’s so beautiful!’ The Orchestre National de France has also embraced this music and has now incorporated it into their repertoire. I hope we will play it regularly in the years to come.

For those who are not familiar with George Enescu, how would you describe his place within the international landscape of his era? Who would you compare him to, or perhaps contrast him with, to help those who don’t know him understand who George Enescu was?

I try to explain to them that Enescu’s music has the grandeur of Gustav Mahler, but the complexity of Richard Strauss, while the language he uses is akin to that of Debussy and Ravel. It creates a completely new world, with harmony that recalls Richard Wagner, a composer Enescu deeply admired. However, the magnitude and grandeur of his music remind me of Gustav Mahler. Like Mahler, Enescu also employs a massive orchestra in his symphonies, with large-scale movements. His Second and Third Symphonies are almost an hour long and through these works, he builds a musical universe that parallels Mahler’s symphonic world.

The complexity of Enescu’s writing is something I have only found in the music of Richard Strauss from the early 20th century. For those who do not know, every musician in the orchestra has an extraordinarily difficult and incredibly beautiful part to interpret, and together they create this vast picture, each contributing with a unique color. But they all need to understand their role in this picture because if they do not, it will become a cacophony, which is what makes it so challenging. I often tell orchestras that everything needs to be played, but we must ensure that nothing stands out individually. It is a fascinating concept because you have to be so transparent at times. Enescu’s music contains many sections where the entire orchestra plays something difficult, but they must be so subtle and soft that no individual sound is heard, creating only the impression of a picture seen through a mist. This is something that distinguishes Enescu from other composers. And of course, the musical gestures make me think a lot about Debussy and Ravel, who were contemporaries of Enescu. The way he uses the entire orchestra, his combinations of instruments and his orchestration strongly resemble those of French composers.

You have referred to Enescu as a personal hero in another interview. Tell us a bit about the power of values to move society forward.

For me, Enescu is undeniably a personal hero, both for the way he created music and for how he managed to captivate the entire world. I have often heard his name mentioned with great admiration and respect in concert halls across the globe. I have seen his works in programs performed even in the United States and come across numerous newspaper articles praising him as an unparalleled genius. Despite this acclaim, Enescu remained a grounded and respectful individual. He did not speak much or engage in politics, especially in matters that did not concern him. His focus was on creating art above all else. He was an exceptional teacher as well as a performer and composer. The values he embodied in everything he did are the same ones I aspire to uphold in my own life.

The fact that I make these significant comparisons for composers beyond Romania underscores an essential point: while Enescu is undeniably a national icon for Romanian culture and art, it is vital to understand that he was much more than just a Romanian composer. Enescu was a figure who stood on par with, if not above, his contemporary composers on the global stage. Placing his music and our culture in a broader, global context elevates its significance. These are values we can take pride in and celebrate. In doing so, we provide something meaningful to pass on to future generations—our children and those who follow. The value of Enescu’s music is a true and lasting legacy. By recognizing and appreciating such values in everyday life, we foster a more beautiful and mature society. Throughout his life, Enescu was an immigrant. This is evident in how he embraced the best aspects of each society he lived in, using them to create something extraordinary – not by abandoning his Romanian roots, but by enriching them. This multicultural perspective -learning in Vienna, composing in Paris and drawing the best from every culture he encountered – offers an inspiring model of how to build a more vibrant and harmonious world.

He serves as an example for all of us because we do not live in an isolated world, confined solely to the culture we inherit without ever broadening our horizons. We live in a global world where it’s essential to appreciate the unique contributions of each individual, weaving them into a beautiful tapestry of identities and personal experiences. This shared beauty not only allows us to find ourselves within it, but also inspires us to create something even more remarkable. The lessons I have learned from Enescu are the kind of values I wish to embrace for myself and my country.

This project will have a continuation, so please tell us more about that.

Indeed, the project continues. Next, we will be recording Enescu’s other works: the Orchestral Suites, the Romanian Poem, the Symphony Concertante and his remaining pieces, in another series of recordings we hope to complete by 2027.

This also marks the conclusion of your term with the National Orchestra of France, and I know there’s a lot of curiosity about what comes next.

My relationship with the orchestra remains very strong and close and we will continue to work on projects together. When I think about most of my conductor colleagues, a seven-year tenure is considered serious and substantial, but it is normal for a music director to move on to another orchestra after such a term. Modern orchestras no longer require a conductor to be with them every day, teaching them how to play; rather, they need different experiences, exposure to new ideas, and fresh approaches to performance. That is why director tenures today typically range from 5 to 10 years. Seven years is an excellent tenure, and it is just the start of strengthening the relationship I’ll continue to have with the orchestra.

Do you have any other upcoming engagements you can share?

At the moment, I am working on balancing the commitments I already have. I do not have anything new to announce yet. I will start my position in Cincinnati this September, and I will be staying in Paris for another two years. I will also continue my collaboration with the WDR Orchestra in Cologne and the ongoing work at the Enescu Festival, which is a massive project. All of these things encourage me to concentrate on what I already have, rather than seek out more opportunities for the time being.

Translated by Alina-Gabriela Ariton, corrected by Silvia Petrescu