Cyrille Dubois, what does it mean to you to have won the ICMA prize in the ‘Baroque Vocal’ category?

It was a great surprise to receive this award. I’ve already made a number of recordings and to see this one awarded by this great international competition makes me feel very proud. Above all, it’s the result of the collaboration with the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles (CMBV) and its artistic director Benoît Dratwicki, the Orfeo Orchestra and the Purcell Choir conducted by György Vashegyi. It’s a long-term partnership that has come to a happy conclusion with this award. So we’re all very happy.

Can you describe your collaboration with these ensembles and György Vashegyi?

I’ve been invited to work with these ensembles in Hungary for a long time, and their conductor, György Vashegyi, has a particular interest in French music. He covers the whole spectrum of the French repertoire, from the Baroque to the Romantic. He has always been drawn to French music, no doubt because of his training with John Eliot Gardiner when he was younger. He has been keen to promote it in his own country through several collaborations with the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles. And it was within this framework that I was able to make my first collaborations with them. So it was natural for me to turn to them to put together a repertoire – or at least a recital – of French Baroque music.

For this CD, we really looked for composers who have been less appreciated over time, such as François Rebel, François Francoeur, Antoine Dauvergne, Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville and François-Lupien Grenet. Of course, specialists will know all these names, but I think they will be a discovery for many people. That’s what I’m interested in: bringing back to life things that may have been lost to history and giving these works a chance to be heard today.

For this CD, we really looked for composers who have been less appreciated over time, such as François Rebel, François Francoeur, Antoine Dauvergne, Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville and François-Lupien Grenet. Of course, specialists will know all these names, but I think they will be a discovery for many people. That’s what I’m interested in: bringing back to life things that may have been lost to history and giving these works a chance to be heard today.

How do you go about this kind of research? Where do you find all these pieces?

Well, it doesn’t happen by itself, whether it’s romantic music, the Lied and mélodie repertoire or baroque music. I think it’s good to divide the tasks a bit, when you have a project like this. There are people who are really specialised in music research and it’s very valuable to bring them together so that we can bring out repertoire that has been forgotten, that has been lost in the libraries.

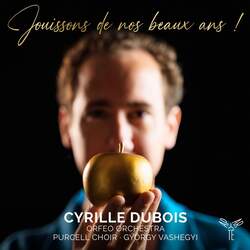

In this respect, the partnership with the CMBV has been invaluable. I had a lot of help from Benoît Dratwicki, who suggested many scores. We read them together and had a decoding session to try to find different characters, different composers and different stories. We tried to bring them all together to produce this recital entitled ‘Jouissons de nos beaux ans’.

The composition of a programme, especially one based on vocal music, is not without importance. How long do you work on the dramaturgy of an album?

The interesting thing about giving a recital that’s not monographic, not just the work of one composer, is to find a theme, an atmosphere that links the different pieces together.

What was sought above all was variety, which was that of the tenor of the time, known as the haute-contre. This consisted of a double quality of singing, very heroic, with very virtuoso passages, but also very tender. I think this is perhaps something that is unique to French music throughout its history. In other words, we have this image of the tenor who can embody the greatest heroes, but also the greatest tenderness, the greatest smoothness in the line. That’s what I like to do with my instrument, to be able to sweep across the whole spectrum of sound and the whole spectrum of intentions. So that’s what you try to find when you put together a programme.

You referred to your voice as an instrument. Could you describe this way of thinking?

The thing about the voice is that everyone sounds different, every timbre is unique. You don’t necessarily get the same impression when you talk about external instruments. A violin can still sound like a violin. A voice is made up of resonators. The different parts that vibrate and resonate are very specific to the singer’s physiognomy. In fact, what I love about voices is the fragility and richness of timbre and colour. I try to tell a story through the story, just by mastering the different timbres of the voice. Getting as close as possible to the emotion, that’s what moves me in a voice and that’s what I look for when I work on my instrument. It’s an exciting pursuit because it’s an evolving one. The voice I had yesterday isn’t the voice I’ll have tomorrow. It’s fascinating to see how much the instrument can change over the years.

You spoke earlier about the two different images of a tenor in 18th century France. Now let’s talk about two different worlds: in your repertoire you move between the mélodie or Lied and the opera. One is intimate, the other takes place on the big stage, sometimes with really big productions. Where do you see the connections?

First of all, of course, it’s the voice and the love of music. In fact, for me these are two completely different exercises that I couldn’t distance myself from. Performing on stage is very, very intense in terms of sharing, synergy and the convergence of energy to create a whole show. Opera is a complete show. To achieve that, you can sometimes have almost 100 people working on the production of a sound, whether it’s the chorus, the orchestra or the soloists. And, of course, there is the singer-actor on stage. The way you use your body to tell a story is something very interesting to explore.

I also have the impression that when I’m alone with a piano or in chamber music, I may have more control over the artistic choices I make. We make choices that are perhaps more in line with our artistic aspirations. So it’s this mix between the two that I find fascinating.

Besides, there is so much to discover in both areas! I could spend my whole life bringing out unreleased works or things that have only been performed once and deserve to be performed again. It’s very rewarding for an artist because the audience listens differently, without any element of comparison. It’s listening to what’s offered, not what’s expected. And that’s another form of listening that I like to encourage in the listener.

Cyril Dubois, do you still play the organ?

Oh no, I stopped a long time ago, but every now and then I get back in front of the instrument at home. But it’s true that it’s quite rare because I’m not at home very often. When I’m feeling a bit nostalgic, I go back to the sheet music and play things I played when I was young. But now it’s an era that’s completely gone.