Das Cembalo einem Sinfonieorchester gegenüber zu stellen, mag auf den ersten Blick sinnlos erscheinen. Wie soll dieses zart zirpende Instrument gegen die Massen an lauten Instrumenten ankommen? Und überhaupt, Cembalo und Moderne? Aber wir sind im 21. Jahrhundert und da geht vieles in sorgfältiger Ausgestaltung. Das klangliche Ungleichgewicht kann man mit dezenter Verstärkung des Tasteninstruments heute so ausgestalten, dass es hörbar ist und die Technik trotzdem im Hintergrund bleibt. Und warum nicht sollte man es nicht in heutige Klangsprache führen? Im Grunde sind die meisten Instrumente ja alte, wenn auch weiter entwickelte.

Poul Ruders, der ohnehin speziell und zugleich vielseitig ist, hat sich, angeregt durch einen Kompositionsauftrag aus Aarhus, an diese Aufgabe gewagt. In reizte auch die Idee, aus der Historie in die Gegenwart zu hören und andersherum auch. Die Sätze sind alle gleich lang mit je sieben Minuten und haben damit etwa barocke Ausdehnung. Herausgekommen ist ein äußerlich klassisches Werk in drei Sätzen, schnell, langsam und lebhaft.

Der langsame Satz geht dann den lyrischen Pfad, wobei die kurz nachhallenden Töne eines Cembalos auch da nicht wirklich eine romantisch ausgiebige Melodie zulassen. Aber der dritte Satz erklingt dann wirklich mechanisch gehämmert. Wobei auch der erste Satz schon, zumindest in der Solostimme, etwas von perkussiv Gestanztem hat.

Ruders gelingt es jederzeit, unabhängig von der technischen Verstärkung, dem Cembalo Freiraum zu lassen.

In dieser Aufnahme der Uraufführung kann das Cembalo seine solistischen Passagen auch dadurch frei vortragen, weil die Komposition die entsprechenden Freiräume zwischen Orchesterpassagen gibt. Aber auch wenn das Ensemble begleitet, schaffen ausgewählte und dezent eingesetzte Instrumentengruppen es, die Balance nicht zu überfordern. Im Klang kann man die Nähe zur Minimal Music mit den gehämmerten und sich nur leicht verändernden Entwicklungen nicht immer leugnen, aber Ruders wäre nicht Ruders, wenn er nicht auf seinem eigenen Weg durch die Komposition führen würde. Insgesamt bietet das Werk eine tragende Mischung aus moderner und auf barocke Sprache zielender Symbiose, die aufgeht. Doch überwältigt mich das Stück wiederum auch nicht. Aber solche Aspekte sind auch eine Frage des persönlichen Geschmacks.

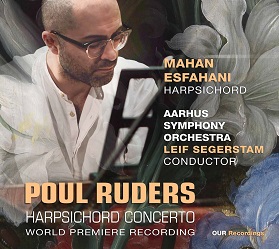

Mit Mahan Esfahani ist einer der momentan gefragtesten Cembalisten unserer Tage zu hören, der neben den spieltechnischen Voraussetzungen die nötige Neugier und das erforderliche musikalische Gespür mitbringt, sich eine solche Komposition zu erobern. Deswegen gelingt ihm eine spannende und intensive Interpretation. Lediglich punktuell mag der Eindruck entstehen, dass alle Beteiligten das neue Werk noch etwas vorsichtig und ehrfurchtsvoll angegangen haben, wo noch mehr Expressivität gut getan hätte.

Mit Leif Segerstam hat das Sinfonieorchester aus Aarhus, das den Kompositionsauftrag vergeben hat, eine ebenso versierten wie jung gebliebenen Dirigenten, der die Fäden angemessen zusammen hält und das Orchester zu rhythmisch animiertem und aufmerksam den Solisten begleitendem Tun formiert.

To juxtapose the harpsichord with a symphony orchestra may seem senseless at first glance. How is this delicately chirping instrument supposed to compete with the masses of loud instruments? And anyway, harpsichord and modernity? But we’re in the 21st century, and a lot goes into careful design. Today, the tonal imbalance can be designed with discreet amplification of the keyboard instrument in such a way that it is audible and the technology still remains in the background. And why not bring it into today’s sound language? Basically, most of the instruments are old, but have been technically improved.

Poul Ruders, who is special and versatile at the same time, dared to take on this task, inspired by a commission from Aarhus. He was also attracted by the idea of listening from the past to the present and vice versa. The movements are all of the same length, seven minutes each, and thus have a more or less baroque extension. The result is an outwardly classical work in three movements, fast, slow and lively.

The slow movement then takes the lyrical path, with the briefly reverberating notes of a harpsichord not really allowing for a romantically expansive melody there either. But the third movement then sounds truly mechanically hammered. Whereby also the first movement already, at least in the solo part, has something of percussive dance.

Ruders succeeds at all times, regardless of technical amplification, in giving the harpsichord free rein.

In this recording of the premiere, the harpsichord is also able to perform its solo passages freely because the composition gives the appropriate spaces between orchestral passages. But even when the ensemble accompanies, selected and discreetly used instrumental groups manage not to overtax the balance. In sound, one cannot always deny the proximity to minimal music with the hammered and only slightly changing developments, but Ruders would not be Ruders if he did not lead through the composition on his own path. Overall, the work offers a sustaining blend of modern and baroque language-targeting symbiosis that works out. Yet, again, the piece does not overwhelm me either. But such aspects are also a matter of personal taste.

Mahan Esfahani is one of the most sought-after harpsichordists of our time, who, in addition to the technical requirements, has the necessary curiosity and musical intuition to perform such a composition. Therefore he succeeds in an exciting and intensive interpretation. Only at certain points the impression may arise that all participants still approached the new work somewhat cautiously and reverently, where even more expressivity would have done good.

In Leif Segerstam, the symphony orchestra from Aarhus, which commissioned the composition, has a conductor who is as accomplished as he is young at heart, holding the threads together appropriately and forming the orchestra into rhythmically animated action that attentively accompanies the soloist.