Die zunächst treibende Kraft hinter dieser Aufnahme ist die Pianistin Jenny Lin, die dann auch die Altistin Sara Couden für die erste Gesamteinspielung der Vokalwerke von Schnabel begeistern konnte. Darunter finden sich als Ersteinspielung Fünf Lieder für mittlere Stimme und Klavier. Schnabel ist als einer der bedeutendsten Pianisten des 20. Jahrhunderts bekannt. Doch komponierte er auch, gewissermaßen heimlich. Damit forderte er sich selbst heraus und verschob nach seinem Belieben die Grenzen der Musik.

Diese Werke sind wohl dem Umstand zu verdanken, dass er die deutsche Altistin Therese Behr nach gemeinsamen musikalischen Auftritten geheiratet hatte. Seine Lieder zeichnen sich durch eine Vielzahl von Stilen aus, die von der Nähe zur Romantik bis hin zu persönlich Formuliertem reichen. Dabei kann man Schnabel eine feinfühlige und inspirierte Umsetzung der Texte zugestehen. Das persönlichste Stück ist das Notturno. Es erinnert aus mehrfacher Sicht an die Verklärte Nacht von Arnold Schönberg, etwa bei der Wahl von Dehmel als Dichter. Und auch in der musikalischen Darstellung ist die Nähe zur zweiten Wiener Schule unüberhörbar. Auch an das Notturno von Richard Strauss mag man erinnert sein. Jedoch geht Schnabel von den Rändern der Tonalität kommend bei seiner Komposition vor.

Ebenso bei den anderen Liedern zeugen Ausdruckskraft und Innovation sowie die Sicherheit der Gestaltung für spannende und fordernde Partituren, die sowohl Sänger wie Pianisten anregen. Da Schnabel selber mit dem Piano vertraut war, liegen diese Partien jedoch ganz natürlich in den Händen. Bei den frühen Liedern überwiegen Einfachheit und Direktheit. Bei den fünf unveröffentlichten Liedern aus der gleichen Schaffenszeit überrascht, wie sie subtil, aber spürbar freier Schnabel hier mit der Struktur umgeht.

Jenny Lin hatte schon Klavierwerke von Schnabel eingespielt und kann somit ihre Erfahrung für den Komponisten einbringen. Zusätzlich zur bereits angelegten interpretationsgerechten Komposition gelingt ihr deshalb eine sensitiv ausformulierte Darstellung, die den eigenen Bedürfnissen und auch denen der Sängerin gerecht wird.

Couden hat bei dieser Erstbefassung mit Schnabels Musik diese als emotional geradlinig aufgefasst. Sie nimmt mit ihrem Ansatz dementsprechend den von Verzweiflung geprägten Text des Notturnos direkt und einfach. Doch auch insgesamt legt sie diesen Maßstab an und bietet so die Lieder in einem kammermusikalischen Ansatz an, der diese Werke vollends trägt. Ihre Artikulation ist an manchen Stellen schwer zu verstehen. Und es gibt einzelne Momente, wie etwa beim Wort ‘hauchen’ in ‘Frühlingsdämmerung’, in denen dieses Wort auch lautmalerisch gesungen, pardon, gehaucht wird, was übertrieben plakativ ist. Auslautverhärtungen vermeidet sie, so dass manche Wortendungen nicht mehr erklingen. Dadurch wird die Artikulation unverständlich, wenn man den Text nicht zur Hand nimmt.

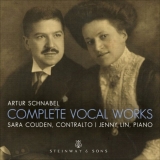

The initial driving force behind this recording is the pianist Jenny Lin, who was then also able to inspire the contralto Sara Couden for the first complete recording of Schnabel’s vocal works. Among them, as a first recording, are Five Songs for medium voice and piano. Schnabel is known as one of the most important pianists of the 20th century. But he also composed, to a certain extent secretly. In doing so, he challenged himself and pushed the boundaries of music as he saw it.

These works are probably due to the fact that he had married the German contralto Therese Behr after performing together musically. His songs are characterized by a variety of styles, ranging from close to romanticism to the personally formulated. Yet Schnabel can be credited with a sensitive and inspired delivery of the texts. The most personal piece is the Notturno. It is reminiscent of Arnold Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht from several points of view, for instance in the choice of Dehmel as poet. And the closeness to the Second Viennese School is unmistakable in the musical performance as well. One may also be reminded of Richard Strauss’ Notturno. However, Schnabel proceeds from the edges of tonality in his composition.

Likewise with the other songs, expressiveness and innovation, as well as the certainty of design, make for exciting and challenging scores that stimulate both singers and pianists. However, since Schnabel himself was very familiar with the piano, these parts come naturally to the hands. In the early songs, simplicity and directness predominate. In the five unpublished songs from the same creative period, it is surprising how subtly, but noticeably more freely Schnabel handles the structure here.

Jenny Lin had already recorded piano works by Schnabel and can thus contribute her experience to the composer. In addition to the already applied interpretive composition, she therefore succeeds in a sensitively formulated performance that does justice to her own needs as well as those of the singer.

Couden, in this first exposure to Schnabel’s music, perceived it as emotionally straightforward. Her approach accordingly takes the text of the nocturne, which is marked by despair, directly and simply. But she also applies this standard overall, offering the songs in a chamber-music approach that fully carries these works. Her articulation is difficult to understand in places. And there are isolated moments, as with the word ‘hauchen’ (aspirate) in Frühlingsdämmerung (Dawn of Spring), in which this word is also sung, pardon, aspirated, onomatopoeically, which is overly striking. She also avoids hardening of final sounds, so that some word endings no longer sound. This makes the articulation incomprehensible if one does not take the text in hand.