Die Geschichte der Madame Bovary, die in der Enge der Ehe und der Gesellschaft des Dorfes ihre Fantasien auslebt und Liebschaften und dann Schulden anhäuft, die sie in den Selbstmord treiben, darf wohl als bekannt angesehen werden. Der Pianist David Kadouch stellt eine gedankliche Verbindung zwischen diesem Roman und der Musik her, die Madame Bovary gehört haben könnte. Neben Werken von Chopin, Liszt und Léo Delibes (Klavierfassung von Ernö Dohnanyi) sind das solche von Louise Farrenc, Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, Clara Schumann und Pauline Viardot. Fast alle Kompositionen scheinen eher das geruhsame Landleben oder die Träume als die sexuellen und anderen Eskapaden hörbar zu machen.

Kadouch nimmt schon zum wiederholten Male so eine thematische Klammer, um seine Einspielung zu umrahmen. Mit seinen Interpretationen wird er hier dem Roman vor allem dadurch gerecht, dass er die ‘sensualité’, also die besondere Empfindsamkeit der Sinne der Madame auf seine Handhabung der Tastatur überträgt. So zeichnet er ein zutiefst feinfühliges Bild der Musik und damit der Zeit. Jedoch ist dieses natürlich nicht frei von Aufwallungen der Seele und entsprechend der Sprache der Musik in seinem Portrait. Mit ebenso klarem Anschlag wie bedachter Strukturierung bietet er eher ein Bild des geruhsamen Lebens in der französischen Provinz als der Kämpfe des Herzens, wenn diese auch nicht fehlen.

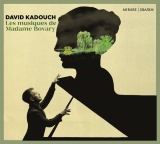

The story of Madame Bovary, who lives out her fantasies in the confines of marriage and village society, accumulating lovers and then debts that drive her to suicide, may well be considered familiar. Pianist David Kadouch makes a mental connection between this novel and the music Madame Léo Delibes (piano version by Ernö Dohnanyi), there are those by Louise Farrenc, Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, Clara Schumann and Pauline Viardot. Almost all of the compositions seem to make audible the tranquil country life or dreams rather than sexual and other escapades.

Kadouch, once again, takes such a thematic bracket to frame his recording. With his interpretations here he does justice to the novel above all by transferring the ‘sensualité’, i.e. the special sensitivity of the senses of the Madame to his handling of the keyboard. In this way he draws a deeply sensitive picture of the music and thus of the time. However, this is of course not free of surges of the soul and according to the language of the music in his portrait. With as clear a touch as he does thoughtful structuring, he offers a picture of the tranquil life in the French provinces rather than the struggles of the heart, though these are not lacking.