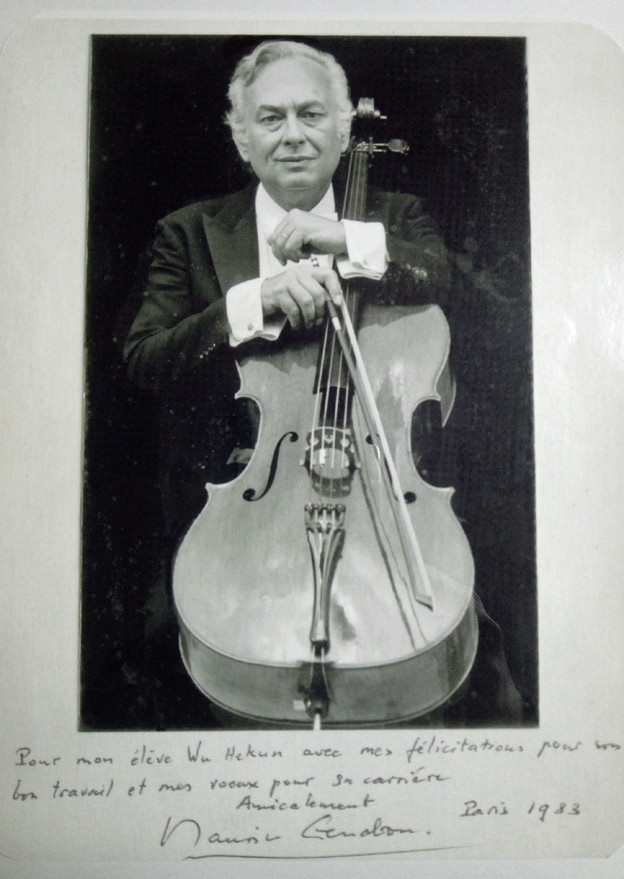

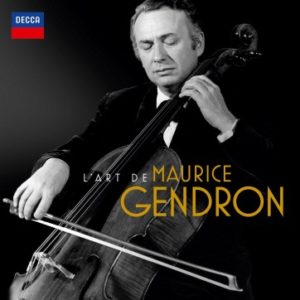

The year 2020 marks the centennial anniversary of Maurice Gendron’s birth. In October 2015, Decca released a 14-CD collection (4823849) L’Art de Maurice Gendron, as a tribute to the legendary cellist of the twentieth century. This is a much anticipated monumental testament to the French master, published a quarter of the century since his passing. Listening to Gendron’s recordings again in chronological order, from 1952 to 1969, is a refreshingly different experience. In spite of the fact that the recordings are from different time periods, the sound quality has captured the natural beauty of his playing without an overly hi-tech re-mastering process. The attractive booklet consists of rare historical photos of Gendron with composers and conductors, such as Hindemith, Mengelberg, Casals and Messiaen, with whom Gendron had collaborated. There are also well-written testimonials by Jean-Charles Hoffelé and Monique Gendron, who add a personal dimension to this most appealing release.

The French school of cello playing occupied almost the entire twentieth-century with a lineage of Les quatre extraordinaires: Pierre Fournier (1906-1986), André Navarra (1911-1988), Paul Tortelier (1914-1990), and Maurice Gendron (1920-1990). These ‘four Musketeers” (Jean-Charles Hoffelé) have made a profound impact on modern cello playing, resonating through the years to the present. Among the four, Gendron was exceptional with his exuberant, gallant and flawless virtuosity avec le bon goût (with good taste), no matter what style. Although Maurice Gendron may not be a household name to the general public and even to the younger generations of cellists, I recall that the late Zara Nelsova (1918-2002) once said in my lesson: “Gendron is the best of our time.”

The French school of cello playing occupied almost the entire twentieth-century with a lineage of Les quatre extraordinaires: Pierre Fournier (1906-1986), André Navarra (1911-1988), Paul Tortelier (1914-1990), and Maurice Gendron (1920-1990). These ‘four Musketeers” (Jean-Charles Hoffelé) have made a profound impact on modern cello playing, resonating through the years to the present. Among the four, Gendron was exceptional with his exuberant, gallant and flawless virtuosity avec le bon goût (with good taste), no matter what style. Although Maurice Gendron may not be a household name to the general public and even to the younger generations of cellists, I recall that the late Zara Nelsova (1918-2002) once said in my lesson: “Gendron is the best of our time.”

No surprise to listeners, Bach’s Six Suites (Edison Prize, 1964) are included in this collection. Gendron played with the spirit of modernity yet with a keen respect for performance practice. In the C minor Suite’s scordatura tuning, for instance, he remains in the lower positions and uses the top open-G-string to maximize the overtones from the instrument. To hear this Suite in its original tuning in the 1960’s was a revelatory aural experience, rare among the great cellists of his generation. Even today, with much research conducted by scholars and performers over the years on the Suites, Gendron’s execution still stands out and remains a touchstone among 60+ recorded versions available. His interpretations are fresh, grandiose, forward-looking, structured and well proportioned, owing to his inimitable sound, and his articulation – his bowing technique reflects the signature of the French school of string playing. Giovanni Battista Viotti declared “Le violon, c’est l’archet” (The violin, it is the bow). Viotti is considered the founding father of the French violin school, which influenced the great ‘devil,’ Niccolò Paganini.

Haydn’s two concertos along with Boccherini’s two concertos are brilliantly performed. Gendron was in top form, superbly supported by orchestras conducted by Pablo Casals (the Haydn D major and Boccherini B-flat major with Orchestre des Concerts Lamoureux, 1960), and Raymond Leppard (the Haydn C major and Boccherini G major with London Symphony Orchestra, 1965). Apparently, it was the only time that the great Catalan master served as conductor alongside his colleague’s performance. Another unique feature of the recordings are Gendron’s performances of his own cadenzas in these four concertos. The Gendron edition of the Haydn D major concerto (published by Schott) has long been the specific edition required for conservatory entrance auditions and major competitions.

The Six Sonatas by Vivaldi are superbly executed, reminding us that these are great works that should be heard more often in concerts. Exquisite phrasing is Gendron’s trademark – in both the Bach and the Vivaldi, he creates a sense of space that allows the music to breath. Stylistically, this sense of time is an important element for the works in the Baroque and Classical periods. The harpsichord and second cello provide sensitive continuo support.

The three sets of Variations by Beethoven are exquisitely executed by both Gendron and pianist Jean Françaix. Here, Beethoven pays homage to Mozart’s arias and with Gendron’s phrasing and sonority, they sing with a luminous quality.

Gendron’s two versions of Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata (1952, 1966) are familiar to many and loved by his fans. Gendron is here supported by Françaix’s piano accompaniment. I am always in awe of Françaix’s sublime harmonic modulation in the second movement! Although the Adagio movement in the 1966 version is slower, it sounds more soulful than the early version. Overall, the 1966 version is more spacious than the 1952 one, both in the playing and the recording quality. Gendron recorded the Arpeggione again in 1975 with Japanese pianist Naoyuki Inoue (not included in this collection, but is available on LP (RCA-Japan). In my opinion, Gendron sounded even more sublime in his later years. On the same LP, the Loccateli Sonata and Gendron’s transcription of La Folia by Marin-Marais were included, which are exceptionally beautiful. I hope his last version of the Arpeggione will be released in the near future.

There are two versions of the Dvorak Concerto (1952, 1965), with Karl Rankl and Bernard Haitink conducting. For a concerto such as Dvorak, the soloist and conductor hold equal roles in the joining of forces. I personally prefer the Rankl version for this reason despite a few minor imperfections in the remastering process while the Silent Woods and Rondo are extraordinary in the Haitink version; Silent Woods is particularly memorable. His earlier version of the Concerto with Willem Mengelberg is not included here (live performance, 1944); it is perhaps superior to his other versions despite the background noise and a few skips in the sound track.

The two versions (1953, 1962) of the Schumann Concerto are included in the set, with Ernest Ansermet and Christoph von Dohnanyi conducting. Both versions are beautifully executed. Harkening back to tradition of the performer-composer, Gendron plays his own cadenza for the third movement in the Dohnanyi version (in lieu of the composer’s); he also alters the original coda. I remember well that in one of my lessons on the Schumann, he was trying to integrate his own cadenza with Schumann’s original one. A side note: another excellent version available, though not included here, is a live performance in 1945 with the Orchestre National de l’ORTF, André Cluytens conducting. Gendron once said to me, “Many consider that the concerto is poorly written, but I think it is mal joué.”

Gendron also had a strong connection to Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations, and the two versions (1953, 1969) in this collection are with Ernest Ansermet and Christoph von Dohnanyi conducting. I hear Gendron sounding freer in the Dohnanyi version. Again, Gendron plays his own cadenza in place of the usual Fitzenhagen one, which makes for quite an ear-opening experience. He plays the fast passages with such finesse that they sound effortless, as if he is shooting the notes to the moon (there is a short video clip of him on YouTube). It is a pity that in both orchestral openings, there are issues of intonation and ensemble in the winds.

The French concertos – Saint-Saëns, Lalo and Fauré’s Elégie — are delightfully played, but unfortunately the orchestral accompaniment does not measure up (Orchestre National de l’Opéra de Monte Carlo, Roberto Benzi).

Disc 7 is comprised of French works such as the Debussy and Fauré Sonatas (Award, Académie Charles Cros, 1966) with Jean Françaix is legendary, and Gendron’s Debussy is superior to the three other Musketeers, in this listener’s opinion. In the Debussy, the images of Pierrot and the moon are revealed vividly through varied timbre, sudden change of moods, and, of course, mastery in utilizing guitar-sounding pizzicati. Fauré’s second sonata in G minor, op. 117 is a late work with a pensive second movement reminiscent of his better-known Elégie, op. 24. The ensemble is superb. Messiaen’s Louange à l’Eternité de Jésus is included here, an unforgettably soulful performance. The treasure trove of five pièces by Françaix is exquisite, consisting of the virtuosic Mouvement perpétuel written for Gendron, plus four other gems that were arranged by Gendron. The Rondino staccato and Mouvement perpétuel trace delicate, wispy, and spirits lines like feathers and bubbles floating in air while the Berceuse, Nocturne and Sérénade have an introspective nature that fit the instrument perfectly.

L’Art de Maurice Gendron also includes piano trio repertoire: Beethoven’s Trio in D major (op. 70, no. 1), Brahms’s C major (op. 87), Schubert’s two trios, and the Tchaikovsky Trio. Gendron joined forces with Yehudi and Hephzibah Menuhin, performing extensively for over twenty-five years. This collaboration was a tour de force and made an important contribution to the repertoire. Besides Menuhin, few other violinists collaborated with Gendron – the great Arthur Grumiaux was one of them and their recording of the Brahms Double Concerto is superb (available on Melos label). Regrettably these two didn’t make more recordings together. The two Brahms String Sextets led by Menuhin are also included and beautifully executed. The DVD version of the B-flat Trio of Schubert is also available (on EMI) and I encourage cellists to check it out – especially his phrasing, and of course, his fingerings. One cannot help to also notice his playing posture, which is ideal.

The last disc, 14 Bis célébres, is a delightful one filled with fourteen miniatures, including Gendron’s own transcriptions of the pièces by Chopin, de Falla, Françaix, Moszkowski, and Paganini. These miniature bonbons will surely please all listeners.

In closing, listening to Maurice Gendron’s performances awakens une époque passée. Gendron’s playing is shaped by his constant search for ideals in both his playing technique and his artistic imagination.