After studying in Seoul you came to Cologne as a student of Aloys Kontarsky. Wasn’t that kind of a cultural shock?

Sure, it was a challenging culture shock. Nowadays, you have more information, so you are better prepared for any changes, even if they are only theoretical. Back then, it was like jumping into a stormy ocean or fire. Even for the physical body, it was a big deal. No language, no family, nothing was familiar, just a constant state of the unknown, and the only thing I had was music. But for the first few months I didn’t even have an instrument to practice on.

Which was your contact with of contemporary music at that time and which role does contemporary music play for you today?

Contemporary music has inspired me a lot to understand the music of past composers, because contemporary music reflects the language and inner state of today. Thus, it was easier for me to understand present music and then to better put myself in the presence of an earlier epoch. Through the intensive study of the music and the joint personal work with Ulrich Leyendecker, I was able to trace back much better the development of the compositional language, through Anton Webern and Alban Berg to Robert Schumann. Now, unfortunately, I have little time to deal with contemporary music. That is a pity.

Due to difficult circumstances in a difficult life you restarted your career quite late, when you were almost 50. Wasn’t that a terrible challenge?

Yes, the decision to start again was really something special. I had to overcome so many inner and outer difficulties. My body wasn’t healthy, I was exhausted from life, my late husband, the pianist Raymund Havenith, died when I was 32. I was alone with my music, I was no more in the music business and I was living in a flat where I couldn’t practice properly. Naturally then you have all kinds of fears and worries inside you that keep whispering that you are doing something quite impossible.

How has the new career path changed your daily life, with your family?

How has the new career path changed your daily life, with your family?

I had to transform myself every day so that I could work. It took me a long time to practice for hours again and at the same time I didn’t want to neglect my family. Luckily, I like doing the housework and cooking. But time and energy are limited, so I had to learn to be economical in every detail. It is also very important to strengthen your mind. Therefore, constant learning on several levels is necessary – like a fugue. I meditated a lot, did psychoanalysis, played at small venues and at school for children, etc. I have seen in my late husband and experienced myself how easy it is to fall into the trap of discarding yourself and life for the sake of performance and career. Yet I look carefully at how to organize it all in a good balance.

After being absent from the concert hall for many years, can you tell us what changes in the musical life and in audiences you noted when you started performing again?

When I started again, it was also a big issue how to get the opportunity to play again. Because without performing, you can’t really develop. And luckily I had good friends who love music and are very experienced in listening. House concerts have been my main stage in the last few years and during Corona anyway. To build myself up again as a soloist I started recording immediately. Regarding the audience I’ve noticed that classical music attracts fewer and fewer young people. To me, the way classical music is presented, is increasingly moving away from its authenticity and substance.

You started right away to make recordings. How important was this aspect for your career?

Recording is a way of dealing with yourself and your music in a very pure and direct way. The microphone listens mercilessly, so you have to learn to listen very sensibly and play very precisely and at the same time perform very vividly because you have no support from an audience. For me it was a good opportunity to develop myself after the long pause.

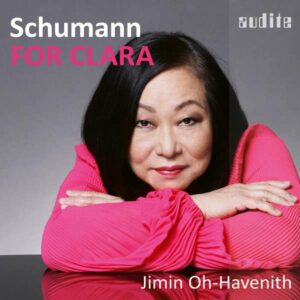

Until now you conceived single programs, but now you start in a series of recordings with works by one composer, Robert Schumann. Is he more important to you than other composers?

At the moment, Schumann is certainly more important to me than other composers. For me, he is the Bach of Romanticism: the way he uses every note is as necessary and absolute as Bach’s, only because of the strong feeling he describes, you don’t perceive it the way you do with Bach. He has a unique art of expression: Very intense, very intimate, very feeling. His music is always about the heart and the appreciation of « being human » with an abundance of inner nuances in a limitless space.

Schumann was mentally ill towards the end of his short life. It has been said that this illness is audible already in some of his early works. What do you think?

Schumann was mentally ill towards the end of his short life. It has been said that this illness is audible already in some of his early works. What do you think?

I don’t think his illness influenced his music. In fact, he became ill because of his talent (not only as a composer), his intelligence, his intensity, his sensitivity, his very challenging life and many other factors that we know and don’t know which finally accumulated to his illness. The human body and mind has to constantly withstand all these processes. And, psychiatric classifications do not help in any way to better understand his music. For me, it is always a miracle that he was able to compose such music in these circumstances and that he could stay in his heart for a ‘short’ or maybe long life.

You have taught a lot, do you continue this activity now that you are a concert pianist again and how important is teaching for you?

I am very grateful for my long teaching career. Teaching is always learning. Working with students is a precious act. At the moment I have taken a break from teaching because doing both might mean that I could not do both mindfully. But I think in the future I will teach again if someone wants to take a journey to his music with my accompaniment.

The music market is overcrowded today, do you think it is hard to fight for getting in appropriate place in this crowd of pianists? What advice would you give a young pianist at the beginning of his career?

Our planet is overcrowded in every category. And unfortunately it doesn’t work that way that pianists then also have more audience. I can only report something from my experience, which is not quite common. My path has given me a very simple view of a very complex situation. I think before you think about your career, just think about your music. Find a teacher who is interested in you (regardless of how great your talent is) and who inspires you. Don’t imitate! There is a very narrow line between imitation and learning. Playing the piano excellently does not mean that you have found your sound and your music. It is a task for a lifetime. I was so obsessed with music that for most of my life I felt that music was the goal in my life, until I realized that music is a boat with which you can cross the river or the ocean. To me, being a pianist means that you create your life with music on the piano as a tool. Ultimately, whatever happens or doesn’t happen, never give up and « EX-PRESS » your music!