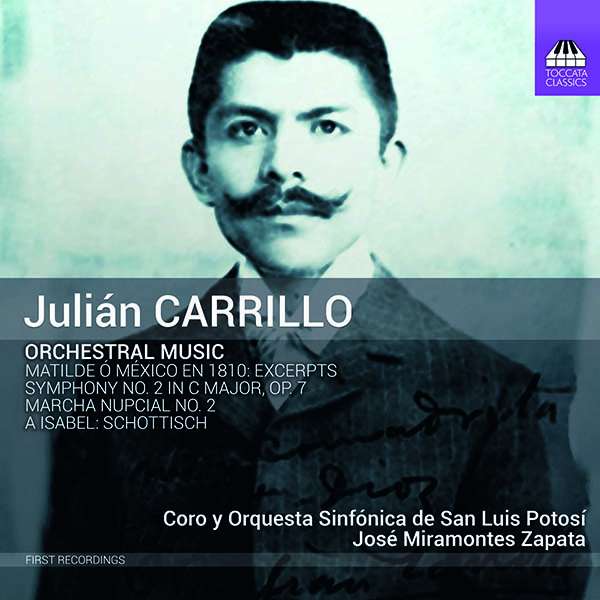

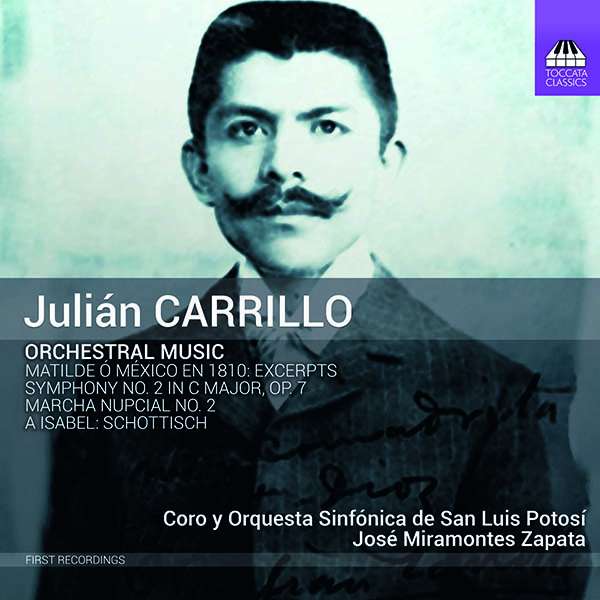

Julian Carrillo: Symphonie Nr. 2 + Orchesterstücke aus Matilde o Mexico en 1810 + A Isabel: Schottisch + Hochzeitmarsch Nr. 2; Orquestra Sinfonica de San Luis Potosi, José Miramontes Zapata; 1 CD Toccata Classics TOCC 0583; Aufnahmen 2010/2015, Veröffentlichung 11/2020 (69'29) - Rezension von Remy Franck

Julian Carrillo: Symphonie Nr. 2 + Orchesterstücke aus Matilde o Mexico en 1810 + A Isabel: Schottisch + Hochzeitmarsch Nr. 2; Orquestra Sinfonica de San Luis Potosi, José Miramontes Zapata; 1 CD Toccata Classics TOCC 0583; Aufnahmen 2010/2015, Veröffentlichung 11/2020 (69'29) - Rezension von Remy Franck

Beim Weltkongress der Jeunesses Musicales im Jahre 1972 in Augsburg traf ich Dolores Carrillo-Flores, die Tochter des Komponisten Julian Carrillo (1875-1965). Sie machte mich, den damals 20-Jährigen, mit den Werken ihres Vaters bekannt. Die völlig neue Klangwelt, die ich nach und nach durch weitere Treffen mit ihr entdeckte, gehörte dem an, was Carrillo Sonido-13 nannte, eine Theorie der mikrotonalen Musik. Während die gängige Oktave in zwölf verschiedene Tonhöhen arrangiert ist, begab sich Carrillo auf die Suche nach dem dreizehnten Ton. Er schrieb einmal: « Der dreizehnte Ton wird der Anfang vom Ende und der Ausgangspunkt einer neuen musikalischen Generation sein, die alles verändern wird. » Nun hatte er freilich mit mikrotonalen Musik, so interessant sie auch sein mag, wenig Erfolg. Es wurden zwar in den Sechzigerjahren in Paris etliche Werke des Sonido 13 aufgenommen, aber ein kommerzieller Erfolg war ihnen nicht beschieden. Ab 1961 und bis 1963 wurden 12 Schallplatten mit Werken von Carrillo eingespielt. Die Ausführenden waren das Orchestre Lamoureux unter der Leitung des Komponisten und auch von Louis de Froment, mit Solisten wie Reine Flachot, Jean-Pierre Rampal oder auch Robert Gendre.

Dolores Carrillo-Flores & Remy Franck in 1973 (FIJM, Israel)

Den Kreuzzug zum 13. Ton begann Carrillo schon früh in seiner Karriere, also noch in jener Zeit, als er in postromantischem Stil komponierte. Er war aber auch Konzertmeister beim Gewandhausorchester in Leipzig und hielt sich lange in Paris auf.

Nach seiner Rückkehr nach Mexiko wurde er Generalinspekteur der Musik im Kulturministerium seines Heimatlandes, Chefdirigent des Nationalen Symphonieorchesters und Direktor am Konservatorium der Hauptstadt. 1950 kehrte er nach Frankreich zurück und dozierte an der Sorbonne. Im Jahre 1960 wurde Balbuceos für Klavier in 16tel Tönen und Orchester unter der Leitung von Leopold Stokowski uraufgeführt. 1962 schrieb Carrillo zu Ehren von Johannes XXIII. seine Misa a S.S. Juan XXIII in Vierteltönen für a-capella-Männerchor. Carrillo starb 1965 im Alter 90 Jahren.

Viel Musik von Carrillo ist gegenwärtig nicht in den Schallplattenkatalogen zu finden. Vor allem die Pariser Aufnahmen mikrotonaler Musik fehlen.

Das Orquesta Sinfonica de San Luis Potosi hat 2017 unter José Miramontes Zapata bei Sterling eine erste CD mit Orchesterwerken herausgebracht, auf der u.a. die erste Symphonie zu hören ist, die ein Kritiker die Fünfte von Brahms nannte.

Toccata Classics bringt nun die Folge davon heraus. Leider ist dies kein besonders erfolgreiches Unterfangen. Die dicht orchestrierte viersätzige Zweite Symphonie hätte ein besseres Orchester verdient als das bescheidene Orquestra Sinfonica de San Luis Potosi und einen besser atmenden, inspirierteren Dirigenten, der die Musik hätte zum Blühen bringen können. Hin und wieder glaubt man, Zapata finde zu etwas mehr Kraft, aber das schlampig artikulierende Orchester macht dann doch nicht mit. Orchestrale Transparenz fehlt völlig, was zum Teil auch an dem engen Klangbild liegt.

Es wäre an der Zeit, dass sich bessere Interpreten der Werke von Carrillo annehmen würden. Und die Ausgrabung der Pariser Aufnahmen, die zu den Schätzen meiner Vinyl-Kollektion gehören, ist ebenfalls überfällig.

At the World Congress of Jeunesses Musicales in Augsburg in 1972 I met Dolores Carrillo-Flores, the daughter of the composer Julian Carrillo (1875-1965). She introduced me, then 20 years old, to the works of her father. The completely new music, which I gradually discovered through further meetings with her, belonged to what Carrillo called Sonido-13, a theory of microtonal music. While the common octave is arranged in twelve different pitches, Carrillo set out in search of the thirteenth tone. He once wrote: « The thirteenth tone will be the beginning of the end and the starting point of a new musical generation that will change everything ». Unfortunately, he had little success with his microtonal music, however interesting it may be. Although several works of Sonido 13 were recorded in Paris in the sixties, they were not commercially successful. From 1961 and until 1963 12 discs with works by Carrillo were recorded. The performers were the Orchestre Lamoureux under the direction of the composer and also of Louis de Froment and with soloists such as Reine Flachot, Jean-Pierre Rampal and Robert Gendre.

Carrillo began the crusade for the 13th tone early in his career, at a time when he was still composing in the post-Romantic style. He was also concertmaster of the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig and spent a long time in Paris.

After his return to Mexico he became Inspector General of Music in the Ministry of Culture of his home country, Chief Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra and Director of the Conservatory of the capital. In 1950 he returned to France and taught at the Sorbonne. In 1960, Balbuceos for piano in 16th notes and orchestra was premiered under the direction of Leopold Stokowski. In 1962, in honour of John XXIII, Carrillo wrote his Misa a S.S. Juan XXIII in quarter notes for a-capella male choir. Carrillo died in 1965 at the age of 90.

Much of Carrillo’s music is currently not to be found in record catalogues. Especially the Parisian recordings of microtonal music are missing.

In 2017, the Orquesta Sinfonica de San Luis Potosi released its first CD of orchestral works under José Miramontes Zapata on the Sterling label, including the first symphony, which one critic called Brahms’ Fifth.

Toccata Classics is now releasing the sequel. Unfortunately this is not a particularly successful venture. The densely orchestrated four-movement Second Symphony deserved a better orchestra than the modest Orquestra Sinfonica de San Luis Potosi and a better breathing, more inspired conductor who could have made the music blossom. Every now and then one thinks that Zapata is finding his way to a little more power, but the sloppily articulating orchestra does not join in after all. Orchestral transparency is completely lacking, which is partly due to the tight sound.

It would be time for better interpreters to take on Carrillo’s works. And the excavation of the Paris recordings, which are among the treasures of my vinyl collection, is also overdue.