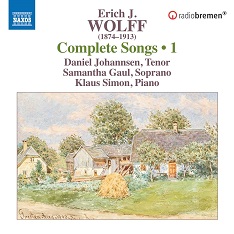

Erich J. Wolff (1874-1913) wurde in Wien geboren, im selben Jahr wie Arnold Schönberg, mit dem er sich später anfreunden sollte. Er änderte seinen Vornamen von Jakob in Erich J., wohl aus Erfahrung mit der nicht immer einfachen Situation für Juden in Wien. Er war ein Jahr lang Zemlinskys Assistent am Carltheater in der Leopoldstadt, und Engelbert Humperdinck zufolge war er zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts der vielleicht bedeutendste Klavierbegleiter Österreichs.

Als Komponist hat er vor allem Lieder geschrieben, aber auch Kammermusik, ein Violinkonzert und ein Ballett. Er starb sehr früh an einer Ohrenentzündung während einer Konzertreise in den USA, am 20. März 1913 in Manhattan. Er war alsbald vergessen, nicht zuletzt, weil die Nazis später die jüdische Musik verboten. Das, und der Umstand, dass er keine Nachfahren hatte, trugen dazu bei, dass er heute so gut wie vergessen ist, obwohl er 168 Lieder komponierte. Etliche Lieder wurden zwar von Thorofon veröffentlicht, allerdings können die Interpretationen mit denen dieser jetzt beginnenden Naxos-Edition nicht mithalten. Trotzdem gefallen sie mir besser, was die Klangbalance angeht, denn bei Naxos wird dem wohl sehr wichtigen Klavier doch eine Rolle eingeräumt, die für die Stimme und damit die Textverständlichkeit in etlichen Liedern von Nachteil ist. Die Text kann man immerhin im Internet bei Naxos finden.

Zu den Dichtern, deren Texte Wolff vertonte, gehören Carl Hauptmann, Jens Peter Jacobsen (Autor der Gurrelieder), Richard Dehmel, Detlev von Liliencron, Tora zu Eulenburg und Otto Julius Bierbaum. Dazu kommen Gedichte aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

Der Pianist Klaus Simon arbeitet seit 2022 an der Gesamtaufnahme aller Lieder mit acht verschiedenen Sängern auf 7 CDs, von denen hiermit die erste veröffentlicht wird.

Simon sagt: « Kein anderes Liedschaffen von deutschsprachigen Komponisten zwischen 1902 (als seine op. 1 erschienen) und 1913 sind insgesamt so gelungen und dankbar als die von Erich J. Wolff. Auch nicht die von H. Pfitzner oder Richard Strauss. Sie bilden vielleicht die letzte Blüte des spätromantischen Liedrepertoires wider. »

Man braucht nur das erste Album der neuen Edition zu hören um festzustellen, wie gut Wolff jeweils den Charakter der Texte trifft, wie individuell er sie behandelt und welche Schönheit der Melodien sich manchmal bei ihm findet. Die Musik ist effektiv unmittelbar ansprechend. Sie ist relativ blumig, lyrisch und üppig melodisch, kann fast ekstatisch aufschwingen, erfordert vom Sänger aber auch die Fähigkeit zu Verhaltenheit und Intimität. Diesen Anforderungen wird Tenor Daniel Johannsen absolut gerecht. Er kann seine flexible Stimme diesen changierenden Stimmungen und ihrem Narrativen gut anpassen. Er führt uns meistens mit einvernehmender Stimme in die Welt Erich Wolffs ein. Dennoch komme ich nicht umhin, Johannsen vorzuwerfen, dass seine immer klare Stimme manchmal etwas zu scharf klingt. Wenn er voll aufdreht (etwa in den Tora zu Eulenburg-Liedern), klingt er mehr nach Wagners Loge als nach einem romantischen Liedsänger. Aber ausdrucksvoll ist er immer, und voll engagiert. Sein theatralisches Talent und sein Gespür für das Drama im Text zeigt er auch in den Pierrot-Melodramen als Erzähler.

Samantha Gaul bringt ihren charmanten Sopran in zwei der Wunderhorn-Lieder ein. Klaus Simon trägt mit seiner starken, prägnanten Rhetorik am Klavier ebenso viel zum Höreindruck bei wie Johannsen. Er spielt hochkonzentriert, voller Spontaneität und spannungsvoller Energie.

Und so kann man diese Edition nicht nachdrücklich genug begrüßen. Wolff gehört definitiv zurück in die heutige Liederwelt.

Erich J. Wolff (1874-1913) was born in Vienna in the same year as Arnold Schönberg, with whom he would later become friends. He changed his first name from Jakob to Erich J., probably out of experience with the not always easy situation for Jews in Vienna. He was Zemlinsky’s assistant at the Carltheater in Leopoldstadt for a year and, according to Engelbert Humperdinck, he was perhaps the most important piano accompanist in Austria at the beginning of the 20th century.

As a composer, he mainly wrote songs, but also chamber music, a violin concerto and a ballet. He died very young of an ear infection during a concert tour in the USA, on March 20, 1913 in Manhattan. He was soon forgotten, not least because the Nazis later banned Jewish music. This, and the fact that he had no descendants, contributed to the fact that he is virtually forgotten today, although he composed 168 songs. A number of songs have been published by Thorofon, but the interpretations cannot keep up with those of this Naxos edition, which is now beginning. Nevertheless, I like them better as far as the sound balance is concerned, because on Naxos the piano, which is very important, is given a role that is disadvantageous for the voice and thus for the intelligibility of the lyrics in a number of songs. The texts can at least be found on the Naxos website.

Among the poets whose texts Wolff set to music are Carl Hauptmann, Jens Peter Jacobsen (author of the Gurrelieder), Richard Dehmel, Detlev von Liliencron, Tora zu Eulenburg and Otto Julius Bierbaum. Poems from Des Knaben Wunderhorn are also included.

Pianist Klaus Simon has been working on the complete recording of all the songs with eight different singers on 7 CDs since 2022, the first of which is being released here.

Simon says: « No other song works by German-speaking composers between 1902 (when his op. 1 was published) and 1913 are as successful and grateful overall as those by Erich J. Wolff. Not even those of H. Pfitzner or Richard Strauss. They perhaps represent the last flowering of the late Romantic lied repertoire. »

You only have to listen to the first album of the new edition to realize how well Wolff captures the character of the texts, how individually he treats them and what beautiful melodies he sometimes finds. The music is immediately appealing. It is relatively flowery, lyrical and lushly melodic, can soar almost ecstatically, but also requires the singer to be capable of restraint and intimacy. Tenor Daniel Johannsen absolutely meets these requirements. He can adapt his flexible voice well to these changing moods and their narrative. He mostly introduces us to the world of Erich Wolff with an agreeable voice. Nevertheless, I can’t help but criticize Johannsen’s always clear voice for sometimes sounding a little too sharp. When he turns up the volume (for example in the Tora zu Eulenburg songs), he sounds more like Wagner’s Loge than a romantic lieder singer. But he is always expressive and fully committed. He also shows his theatrical talent and his flair for the drama in the text in the Pierrot melodramas as the narrator.

Samantha Gaul brings her charming soprano to two of the Wunderhorn songs. Klaus Simon’s strong, incisive rhetoric at the piano contributes just as much to the listening experience as Johannsen. His playing is highly concentrated, full of spontaneity and exciting energy.

And so this edition cannot be welcomed emphatically enough. Wolff definitely belongs back in today’s song world.