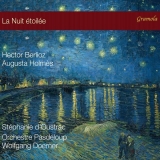

Inspiriert von sechs Gedichten von Théophile Gautier aus der Sammlung ‘La comédie de la mort’ (Die Komödie des Todes), wurde der Zyklus Nuits d’Eté von Hector Berlioz 1841 uraufgeführt, also in der Zeit als Berlioz vor den Trümmern seiner Ehe mit Harriet Smithson stand und kurz bevor er eine Affäre mit der Sängerin Marie Recio begann, die er 1854 heiratete, nach dem Tod von Harriet, von der er getrennt gelebt hatte, weil eine Scheidung damals in Frankreich nicht möglich war.

Der Liederzyklus schildert schwüle Sommernächte voller Schwermut in kleinen Geschichten, die von der unbeschwerten Frühlingsliebe bis hin zu Einsamkeit und Tod reichen. In einem gewissen Sinn ist der Zyklus die musikalische Grablegung seiner einst flammenden Liebe zu Harriet. Mit ihrer dunkel gefärbten und äußerst warmen Stimme gelingt Stéphanie d’Oustrac eine bewegende Interpretation, voll von dunklem Pathos, wie man ihn nicht oft so ausgeprägt und vereinnahmend in diesen Liedern hört, die sie mit Trauer, aber mit einer warmherzigen Stimme auch mit nicht verblassender Liebe erfüllt. Rein vokal gesehen kann die Stimme durchaus gefallen, wenn sie auch in der Höhe machmal etwas scharf wird und im unteren Register zu etwas hohlen Brusttönen neigt.

Das 1888 von Augusta Holmès komponierte kurze Stück Ludus pro Patria mit gesprochenen und gesungenen Text führt zu Cléopâtre (auch als La Mort de Cléopâtre bekannt) von Hector Berlioz. Das Jugendwerk ist schon oft nicht sehr gut aufgenommen worden, und wenn Wolfgang Doerner, das Orchestre Pasdeloup und Stéphanie d’Oustrac auch eine vitale Interpretation davon liefern, so klingt die Stimme der Mezzosopranistin manchmal etwas unausgeglichen und vom Text versteht man so gut wie nichts. Da denkt man wehmütig zurück an die Interpretation von Véronique Gens oder an jene der amerikanisch-russischen Sängerin Jennie Tourel, die vom New York Philharmonic unter Leonard Bernstein so großartig begleitet wurde. Vergleicht man den schlanken, dramatischen Sound dieser mittlerweile fast 50 Jahre alten Aufnahme mit dem etwas breiigen und wenig transparenten Klang des Orchestre Pasdeloup, kann man nur bedauern, dass diese Berlioz-Komposition in dieser Einspielung so sehr misshandelt wird.

In den Nuits d’Eté behauptet sich das Orchester besser, wendiger und ausdrucksvollere, bleibt aber wegen der Aufnahmetechnik allzu mittig und etwas matt.

Und so wird mit diese CD vor allem wegen der warmherzigen Interpretation der Nuits d’Eté durch Stéphanie d’Oustrac in Erinnerung bleiben.

Inspired by six poems by Théophile Gautier from the collection ‘La comédie de la mort’ (The Comedy of Death), the cycle Nuits d’Eté was first performed by Hector Berlioz in 1841, the time when Berlioz was facing the ruins of his marriage to Harriet Smithson and shortly before he began an affair with the singer Marie Recio, whom he married in 1854, after the death of Harriet, from whom he had been just separated because divorce was not possible in France at the time.

The song cycle depicts sultry summer nights full of melancholy in little stories that range from carefree springtime love to loneliness and death. In a sense, the cycle is the musical burial of his once blazing love for Harriet. With her darkly colored and extremely warm voice, Stéphanie d’Oustrac succeeds in a moving interpretation, full of gloomy pathos. She fills the songs with sadness, but with a warm-hearted voice also with a lasting love. From a purely vocal point of view, the voice is quite pleasing, even if it becomes sometimes a bit sharp in the treble and tends to somewhat hollow chest tones in the lower register.

The short piece Ludus pro Patria, composed in 1888 by Augusta Holmès with spoken and sung text, leads into Cléopâtre (also known as La Mort de Cléopâtre) by Hector Berlioz. The youthful work has often not been very well recorded and even if Wolfgang Doerner, the Orchestre Pasdeloup and Stéphanie d’Oustrac deliver a vital interpretation of it, the voice of the mezzo-soprano sometimes sounds a bit unbalanced and one understands almost nothing of the text. One thinks wistfully back to the interpretation of Véronique Gens or to that of the American-Russian singer Jennie Tourel, who was so magnificently accompanied by the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein. Comparing the lean, dramatic sound of this recording, now nearly 50 years old, with the somewhat mushy and less transparent sound of the Orchestre Pasdeloup, one can only regret that this Berlioz composition is so badly recorded in this recording.

In the Nuits d’Eté the orchestra sounds better, more agile and expressive, but because of the recording technique it remains all too centered and somewhat dull.

And so this CD will remain in my memory above all because of the warm-hearted interpretation of the Nuits d’Eté by Stéphanie d’Oustrac.