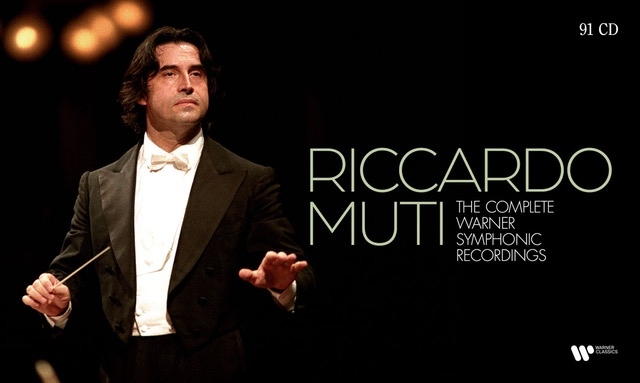

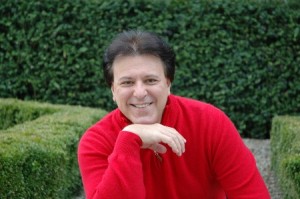

Wie viele seiner Kollegen hat der italienische Dirigent Riccardo Muti, der Ende Juli 80 wird, für viele Labels aufgenommen, für EMI, für Deutsche Grammophon, Sony und zuletzt für das Chicagoer Label CSO Resound. Warner bringt nun Mutis Orchesteraufnahmen von EMI heraus.

WERKE VON TCHAIKOVSKY

Riccardo Muti ist ein ausgezeichneter Tchaikovsky-Dirigent. Das hat er in seinen Aufnahmen einzelner Symphonien bewiesen, nie freilich so überdeutlich wie in der Einspielung der Manfred-Symphonie, wo der Dirigent eine großartige Leistung vollbringt. Seine Interpretation ist spannungsgeladen, hat Profil und Ausdruckskraft wie kaum eine andere, sie ist dramaturgisch effektvoll, aber nie vordergründig angelegt, sie ist im Klang voll und wohlproportioniert, hervorragend verschmolzen und doch durchhörbar bis ins kleinste Detail. Die Musik strömt breit, wobei die angesprochenen Effekte in den symphonischen Ablauf eingebettet bleiben. Das Spiel des Philharmonia Orchestra ist von höchster Qualität, ebenso die Aufnahme in ihren rein technischen Aspekten.

Tchaikovskys 2. Symphonie, die Kleinrussische, enthält viele Elemente russischer Folklore. Muti sorgt dabei für die richtige Dosierung, obschon er die symphonische Brillanz mehr hervorstreicht als Rostropovich oder Kitajenko, deren Interpretationen ohne Zweifel ‘Kleinrussischer’ sind als jene von Riccardo Muti, der das Philharmonia Orchestra zu einer grandiosen Leistung anfeuert. Allerdings gelingt es dem Dirigenten schon vor der Interpretation der 2. Symphonie, den Hörer auf seine Seite zu bringen. Vorab erklingt nämlich die Fantasie-Ouvertüre Romeo und Julia, und die ist sehr programmbezogen. Der Dirigent erzählt die unglückliche Liebesgeschichte gefühlvoll, bringt Liebe, Leidenschaft und Kampf gut zum Ausdruck, weil er die gegensätzlichen Klangblöcke des Werks kontrastvoll gegenübergestellt.

Tchaikovskys Dritte liegt in einer Einspielung, mit der man auch jene Leute für dieses Werk begeistern kann, die sonst nur die Symphonien 4 bis 6 hören. Die Einleitung baut Muti spannungsvoll auf, bereitet misterioso jenes Allegro vor, das Tchaikovsky ‘brillante’ wollte, und das Muti hier explosiv-brillant inszeniert. Die langsamen Sätze dirigiert der Dirigent mit sehr viel Gefühl, das Scherzo mit Kraft, und die Finalpolonaise beschließt hymnen- ja apotheosenhaft das Werk. Das Philharmonia Orchestra, das unter Muti hörbar aufblüht, spielt enthusiastisch.

In Tchaikovskys Vierter Symphonie, die Muti ebenfalls an der Spitze des Philharmonia Orchestra London dirigiert, braucht der Maestro etwas länger Zeit, um so richtig warm zu werden, aber schon die zweite Hälfte des ersten Satzes kann begeistern. Eine ebenfalls sehr zwingende Gestaltung gelingt Muti im zweiten Satz, der dadurch deutlich aufgewertet wird. Herrlich, wie er in diesem Satz die Flöte zur Geltung bringt und überhaupt die Holzbläser sehr hervorstechen lässt. Das verspielte Scherzo ist Muti sehr reizvoll gelungen. Großartig auch der letzte Satz, berauschend, ekstatisch.

Riccardo Muti beendet seine Einspielung der Tchaikovsky-Symphonien nach einer exzellenten Interpretation der Fünften mit der Sechsten, der Pathétique. Seine Interpretation ist nicht nur eine mehr in der langen Serie, die auf Schallplatte verfügbar sind, es ist eine der besten davon. Mutis ohnehin große Leidenschaftlichkeit wird in diesem Werk noch gesteigert, sie bekommt ekstatische, wilde Züge. Er treibt das Orchester an wie kein zweiter, kraftvoll, ergreifend und versetzt den Hörer völlig in den Rausch von Tchaikovskys Musik. Keinen Moment lang lässt er die Spannung absinken. Er verliert sich nicht in Äußerlichkeiten, sondern sorgt für eine geschlossene aussagekräftige Interpretation, der das herrliche Spiel des Londoner Philharmonia Orchestra sehr zugute kommt.

Mutis Interpretation der Tchaikovsky-Ballette ist spektakulär in der Gestaltung, feierlich im Ton, eher breit in der Anlage, immer nahe am Geschehen und von daher auch in allen Formen zu begründen.

Der Klang ist luxuriös, das Orchester aus Philadelphia glänzt und brilliert in beiden Suiten. Eigentlich kann sich das Ohr (in diesen Werken) nichts Schöneres wünschen: durch die handlungsbezogene Interpretation sieht das Auge durchs Ohr hindurch mit!

Mit dem Solisten Andrei Gavrilov und dem Philharmonia Orchestra London hat Muti das Erste Klavierkonzert von Tchaikovsky eingespielt. Gavrilov konzipiert den Klavierpart sehr gewichtig, ohne ihn aber breit klingen zu lassen. Auch ist er nicht übermäßig pathetisch. Muti begleitet nicht nur sehr aufmerksam, er drapiert auch so manche Passage neu, er färbt sehr kräftig und würzt den Klang recht deftig. Beide betonen – und Gavrilov macht es mit einem sehr interessanten Farbverlauf deutlich – das Maestoso des ersten Satzes. Das Allegro con spirito hätte ich mir freilich etwas spannender gewünscht. Das Andantino hat eine sehr langsame Gangart und unterscheidet sich kontrastreich vom Prestissimo des 2. Satzes, das, wie das abschließende Allegro con fuoco, von einem quirligen und sehr präsenten Spiel des Solisten lebt. Im Großen und Ganzen aber ist dies keine Aufnahme fürs Spitzenfeld.

Eine weitere Tchaikovsky-Platte enthält die Ouvertüre Solennelle 1812 und die Streicherserenade, also ein Programm, das auf Anhieb nicht zusammenzupassen scheint, das aber, so wie Muti es sieht, doch bestens zusammengeht. Die 1812 nämlich ist bei Muti kein knalliges Kriegsdrama, sondern eher eine musikalische Anklage des Krieges, ‘un sombre tableau’, wie die Franzosen sagen würden. Der Dirigent geht das Werk mit viel Leidenschaft und noch mehr Gefühl an, verleiht ihm so eine bedeutungsschwere Aussagekraft, die man sonst aus der 1812 nicht heraushört. Selbst zum Schluss vermeidet er das Spektakuläre, weshalb das musikalische Geschehen dann gar groteske Züge annimmt. Da der erste Satz der Streicherserenade der so unfeierlich gespielten Ouvertüre Solennelle unmittelbar folgt, nimmt er fast religiöse Züge an, so als sei es ein Bekenntnis zum Frieden. Auch dem zweiten Satz fehlt die äußere Eleganz, die ihm sonst anhaftet. Dafür zeigt er sehr viel innere Anmut. Verhalten, fast inbrünstig klingt der dritte Satz. Im vierten schließlich ändert sich die Atmosphäre nur ganz langsam, bis das Werk dann in einem freudig bewegten Schluss ausklingt.

WEITERE RUSSISCHE KOMPONISTEN

Modest Mussorgskys Bilder einer Ausstellung in der Orchestrierung von Maurice Ravel ist ein Stück, das sich hervorragend eignet, um die spieltechnischen Qualitäten eines Orchesters unter Beweis zu stellen. Die Musiker des Philadelphia Orchestra bringen in ihrer Mischung aus Power, Brillanz und Hellhörigkeit die besten Voraussetzungen mit, um die Bilder-Partitur eindringlich zu gestalten. Und Muti nutzt dieses Können aus, um die Klangwelt Ravels auszureizen und somit eine eigentlich auch sehr französische Bilder-Interpretation zu liefern. Durch eine überaus genaue Beachtung des Details kommt die Weite der musikalischen Gedanken und Phantasien voll zum Ausdruck. Muti gestaltet das Werk aus einer souveränen inneren Ruhe heraus, ohne jedes Pathos. So kommt eine intensive, aber nie ekstatische Darstellung von plastischer Beredtheit zustande, die einen wichtigen Platz in der Diskographie einnimmt. Das Orchester ist auch in Eine Nacht auf dem Kahlen Berg glänzend disponiert und demonstriert höchste Brillanz.

In Philadelphia entstand auch die Einspielung von Rimsky-Korsakovs Scheherazade. Muti gelingt wiederum eine tolle Mischung von Sensualität, orientalischer Üppigkeit und brillanter Rhythmik. Interessant sind auch manche fein herausgearbeitet orchestrale Details.

Eine in ihrer Vehemenz packende, durch ihren Rhythmus aufregende Version von Stravinskys Le Sacre du Printemps liefert Riccardo Muti an der Spitze des Philadelphia Orchestra. Muti beherrscht hier das Orchester so gut wie das Orchester die Partitur. Eine Spitzenleistung!

Und dann sind da noch Prokofievs Romeo und Julia-Suiten, denen Muti Leben einhaucht. Ach, was sind das doch für Gefühle, die da verströmt werden, wie pulsiert diese Musik! Muti dirigiert sie mit südländischem Temperament, Leidenschaft und Glut. Auch ohne die Programmfolge zu kennen, kann der Hörer jeden Teil der Suiten mühelos situieren. Das Philadelphia Orchestra vollbringt eine Meisterleistung an Präzision und Virtuosität.

Nicht weniger hervorragend sind die Aufnahmen von Prokofievs Iwan der Schreckliche im Arrangement von Abram Stasevich und der Sinfonietta. Muti dirigiert die Filmmusik kraft- und spannungsvoll, passend dramatisch, mit großartigen Höhepunkten. Das Philharmonia Orchestra spielt brillant, und die Solisten, allen voran Irina Arkhipova und Anatoly Mokrenko, sind hervorragend.

Eine Sternstunde der Schallplattengeschichte! So muss man wohl, ohne auch nur ein wenig zu übertreiben, Riccardo Mutis Aufnahme der Stravinsky-Ballettsuite Petrouchka bezeichnen. Unter Mutis Hand gewinnt die Komposition in faszinierender Weise an Farbigkeit, an leuchtender Kraft, an rhythmischer Härte und zupackender Tiefe. Auch durch die flexible Gestaltung, größere dynamische Freiheiten und eine starke Differenzierung des Orchesterklangs besticht diese Interpretation, deren Lebendigkeit, innere Spannung und äußere Nervosität kaum von einem anderen Dirigenten erreicht wird. Riccardo Muti weiß, wovon Stravinskys Musik lebt! Und das Philadelphia Orchestra hat es vollends begriffen.

Rachmaninovs Konzerte für Klavier und Orchester Nr. 2 & 3 und die Rhapsodie über ein Thema von Paganini hat Muti 1986 und 1989 mit Andrei Gavrilov und dem Philadelphia Orchestra aufgenommen. Gavrilov spielt virtuos und feinfühlig, durchwegs klangschön, und er wird von einem leidenschaftlich mitatmenden Muti mit dem phänomenalen Philadelphia Orchestra unterstützt. Insbesondere die langsamen Sätze sind ergreifend schön gelungen.

Die Gesamtaufnahme der drei Scriabin-Symphonien mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra ist ein Meilenstein in der Diskographie dieser Kompositionen.

Orchestral ausgewogen überzeugen sie mit einem reichen und sonoren Klangbild. Muti investiert sich voll für diesen Komponisten, und er zieht in seinen Interpretationen gleich mit Abbado, bleibt aber wohl ein klein bisschen hinter den in ihrem russischen Charakter authentischeren Aufnahmen von Svetlanov und vor allem von Dmitrij Kitajenko zurück.

In Riccardo Muti’s Diskographie ist Shostakovich kein Komponist, der oft auftaucht. Mit dem Chicago Symphony gibt es bei CSO Resound eine gute Aufnahme der 13. Symphonie, und diese Kollektion enthält eine Einspielung der Fünften mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra, die aber bestenfalls wegen des superben Spiels des Orchesters beeindrucken kann. Vor allem die Blechbläser des amerikanischen Orchesters liefern einen phänomenalen Beitrag zum Klangbild. Doch Muti dringt nicht wirklich in die Musik ein und liefert eine poliert-oberflächliche Interpretation, die an der Bitterkeit und Intensität der Gefühle vorbeigeht. Die Art wie er an Shostakovich herangeht, passt schon besser zur Festouvertüre, die als Füller auf dieser CD figuriert.

DVORAK & BRUCKNER

Die effektvollen Paukenschläge im ersten Satz von Antonin Dvoraks 9. Symphonie (Aus der Neuen Welt) und die gewagten Tempoveränderungen lassen zunächst die Stirn runzeln. Im weiteren Verlauf des Satzes beruhigt sich der Dirigent etwas, und der zweite Satz gelingt ihm sehr schön und lyrisch, doch im Scherzo und im Finale gibt es wiederum störende Mätzchen, die diese Interpretation manieriert werden lassen.

Eine Referenzeinspielung des Violinkonzerts von Antonin Dvorak legen Muti und Kyung-Wha Chung zusammen mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra vor. Beide verbinden einerseits temperamentvoll zupackendes und feinfühlig zartes Musizieren und liefern damit eine leidenschaftlich gestische Interpretation, wie man sie sich schöner und erfüllter nicht vorstellen kann.

DEUTSCH-ÖSTERREICHISCHE SYMPHONIK

Die drei M-Platte – Mozart, Mutter, Muti – wurde seinerzeit von EMI nicht umsonst aus der normalen Produktion gebührend herausgehoben: es ist eine besondere Aufnahme, die hier zu hören ist. Anne-Sophie Mutter spielt die Violinkonzerte Nr. 2 und 4 von Mozart mit einer Inbrunst, dass einem das Herz höher schlägt. Technisch ist die Mutter dabei so perfekt, wie selbst Oistrach es nicht war. Und wenn wir schon bei diesem Vergleich sind: was der Geiger Oistrach und der Dirigent Oistrach in einer Person nicht zustande brachten, nämlich homogenes und aufeinander abgestimmtes Spiel der Sologeige und des Orchesters, das schaffen Riccardo Muti mit dem Philharmonia Orchestra und Anne-Sophie Mutter in kongenialer Weise. Dieses im Gefühlsausdruck durchaus unpathetische, im Zusammenspiel aber berückende Miteinander, das Ineinandergreifen beider ‘Klangkörper’, ist von einer seltenen Expressivität, die weder Oistrach noch Menuhin (ebenfalls Dirigent und Solist) erreichten.

Svjatoslav Richter ist der Solist im 22. Klavierkonzert KV 482 von Mozart, 1979 mit dem Philharmonia Orchestra aufgenommen. Es ist eine besonders kraftvolle, deutlich in Richtung Beethoven weisende Interpretation, die Muti ebenfalls mit dem Orchester sehr kontrastreich und kräftig konturiert werden lässt. Interessant ist, dass Richter die Kadenzen von Benjamin Britten spielt, die dieser für den russischen Pianisten komponiert hat und die im Konzert für einen gewollt starken Kontrast sorgen.

Nicht weniger frisch und kraftvoll sind die 24. Symphonie KV 182, die 25. KV 183 und die 29. KV 201 (mit dem New Philharmonia). Die mit den Berliner Philharmonikern gemachte Einspielung der Jupiter-Symphonie ist sehr ausgewogen, vital und farbig.

Die Gesamteinspielung der Beethoven-Symphonien mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra ist überraschend, denn Riccardo Muti spielt in nahezu idealer Weise mit den Tempi, gibt der Musik Zeit und Raum, sich zu entfalten. Mutis Interpretation ist klassisch schön, nuancenreich, im Grunde auch sehr lyrisch und immer bedeutsam in der Gestik. Ganz besonders deutlich wird das im 3. Satz der durchgehend exzellenten 9. Symphonie, den Muti ergriffen singen lässt.

Eine überaus heiter-idyllische Fassung von Beethovens 6. Symphonie, der Pastorale, hat Muti mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra eingespielt. Mit unendlich viel Liebe zum kleinen, pittoresken Detail, als wollte er mit wirklich jeder Note Beethovens Naturbild nachzeichnen, gelingt Muti eine Interpretation, die sich durch ihre ruhige Schönheit auszeichnet.

Zusätzlich gibt es noch das Klavierkonzert Nr. 3 mit Svjatoslav Richter als Solist sowie 3 Ouvertüren von Beethoven, Leonore Nr. 3, Die Weihe des Hauses und die Fidelio-Ouvertüre. Dabei ist mir bewusst, dass der berühmte russische Pianist Beethovens drittes Konzert bereits 1960 in Wien mit Kurt Sanderling als Dirigent für die DGG aufgenommen hatte, und auch diese Aufnahme ragt aus dem Überangebot einsam hervor. Richter spielt in beiden Fällen die Original-Kadenz des Komponisten im ersten Satz derart beeindruckend, dass einem schier der Atem stockt.

Die Schubert-Symphonien hat Muti mit den Wiener Philharmonikern aufgenommen. Er dirigiert sie zügig und vital, differenziert sie aber sehr gut, so dass ihm sehr charaktervolle Interpretationen gelingen. Reizvoll sind die Ouvertüre und die Bühnenmusik zu Rosamunde, die von Muti recht theatralisch angegangen wird. Die Wiener Philharmoniker folgen ihm aufmerksam in seinem bezugreichen Dirigat und so kommt eine Interpretation zustande, die andere, unverbindlichere, in den Schatten stellt.

Eine gute Werkkopplung gibt es mit Schumanns Symphonie Nr. 1 B-Dur op. 38 (Frühlingssymphonie), sowie Mendelssohns Symphonie Nr. 5 D-Dur op. 107 (Reformationssymphonie). Wie Muti die Frühlings-Symphonie anpackt, ist sehr interessant. Bei ihm sprießt mehr als sonst zu hören ist, seine Frühlingsgefühle sind mitreißender als die anderer Dirigenten. Schumanns Werk wirkt hier unbändig, ungezügelt, ganz und gar nicht feierlich, pathetisch oder hymnenhaft, wie man es manchmal hört. Das ist ein Jubilieren, ein Stürmen und ein Drängen, das einen zwingend mitreißt, überwältigt durch seinen musikalisch-melodischen Reichtum, aber auch durch die Innigkeit der Gefühle, etwa im zweiten Satz. 31 Minuten und 40 Sekunden herrlicher Musik gibt es dann auch in der Mendelssohn-Symphonie. Muti gelingen darin einige sehr spannungsvolle Steigerungen. Er zelebriert das Werk nicht, er dirigiert es mit ungeheurer Dramatik. Auch die anderen Symphonie, die Zweite, die Dritte und die Vierte (gekoppelt mit einer schwungvollen Italienischen von Mendelssohn) zeichnen sich durch ein drängendes und flüssiges, hell getöntes und brillantes Musizieren des New Philharmonia aus London aus.

Das Violinkonzert von Schumann geht einem unter die Haut. Es ist eigenwillig gestaltet und enthält ein gerüttelt Maß an Akzentuierungen, die Schumann nicht vorsah: Gidon Kremer, Riccardo Muti und das Philharmonia Orchestra wollten wohl aus dem schwierigen Werk herausholen, was sie nur konnten.

Kongenial haben Muti und sein Solist auch das Violinkonzert von Sibelius erarbeitet. Auch hier freut man sich über ein ausgezeichnetes, spannungsvolles Orchesterspiel und einen an Ideen äußerst reichen Solopart.

Nicht vordergründig-expressiv, sondern ganz tief alle Bereiche menschlichen Fühlens auslotend, das ist die Art, in der Riccardo Muti und Alexis Weissenberg an das 1. Klavierkonzert von Johannes Brahms herangehen. Das Resultat ist anerkennenswert. Da gibt es gedankliches Verweilen, gestresstes Vorüberhetzen, da gibt es Kraft und Kraftlosigkeit, Ruhe und Unruhe: selten haben Interpreten die Kontraste in diesem Konzert so herausgestrichen. Mutis Orchesterarbeit (mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra) ist im Übrigen hervorragend, und Weissenbergs Spiel überrascht ob seiner Klarheit, seiner ‘Ordnung’ und der Manier, wie es sich in das Orchester einfügt. Eine außergewöhnlich gute, mitgestaltende Technik sorgt für vollendeten Hörgenuss.

Von Bruckner hat Muti die Symphonien Nr. 4 und 6 mit den Berliner Philharmonikern aufgenommen. Er interessiert sich in beiden Werken vor allem für den Klang und das, was man dramatisch damit ausdrücken kann, mehr noch, was ein Italiener und ein Operndirigent an vokaler Melodik aus diesen Partituren herausholen kann. Dass bei diesem Procedere auch die Steigerungen bestens bedient werden, ist selbstverständlich. Das ergibt zwei äußerst dynamische und leidenschaftliche Bruckner-Aufnahmen, die durchaus ihren Platz in der Diskographie haben, nicht zuletzt wegen des brillanten Musizierens der Berliner Philharmoniker.

Wer die Faust-Symphonie von Franz Liszt nicht gut kennt, kann sicher aber an den Préludes desselben Franz Liszt ermessen, ob eine Interpretation gut ist oder nicht. Beide Werke sind in einem Album vereint, aufgenommen durch das Symphonie-Orchester von Philadelphia unter der Leitung von Riccardo Muti.

Muti ist mit diesen Einspielungen wiederum ganz Großartiges gelungen. Les Préludes kann als Beispiel für die Güte beider Interpretationen stehen. Denn so wie der Dirigent diese Tondichtung dramaturgisch völlig neu zeichnet, sie gewissermaßen neu strukturiert, der gerne erhaben-pathetisch gestalteten Musik Leben einhaucht, das hat – trotz offensichtlichen Bemühens – nicht einmal ein Karajan geschafft.

Und Riccardo Muti verfährt in der Faust-Symphonie – die ja eigentlich nichts anderes ist als eine Folge von drei Tondichtungen zu den Themen Faust, Gretchen und Mephisto – nach denselben Rezepten: resolutes Suchen nach dramatischen Abläufen, nach Programmpunkten, die an eine Handlung erinnern sollen, mit sämtlichen damit zusammenhängenden Motiven und Gefühlsmomenten. Die Musiker aus Philadelphia folgen ihrem Dirigenten trotz seiner streckenweise furiosen Tempi in glänzender Disposition und mit bemerkenswertem Engagement.

Ein sinfonisches Drama um Natur und junge Liebe nennt Michael Kennedy in seinem Einführungstext die 1. Symphonie von Mahler. Eine treffende Bezeichnung, zumindest für Riccardo Mutis warme, beschwingte, von positiven, beglückenden Gefühlen überquellende Interpretation. Dabei vermittelt Muti nicht nur dieses naturverbundene, vom Frühlingserwachen geprägte Gefühl der Freude, des Glücks, er kümmert sich auch um die Effekte, die Mahler so sehr am Herz lagen; er pflegt Farben, arbeitet Instrumentalwirkungen heraus. Und welch ein herrliches Orchester! Welche beeindruckende Bläserschar! Welches Streicherkorps! Was für hervorragende Holzbläser! Welche Geschmeidigkeit! Welcher Klang! Eine rundum beglückende Aufnahme!

FRANZÖSISCHE UND ITALIENISCHE KOMPONISTEN

Muti hat einige Werke französischer Komponisten aufgenommen, darunter auch die Symphonie von César Franck. Ihm gelingt keine besonders kohärente und schon gar keine typisch französische Interpretation, aber er arbeitet doch mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra in nicht uninteressanter Weise an den Texturen der Musik, was dann auch immer wieder zum Aufhorchen führt.

Roméo et Juliette von Berlioz wurde in Philadelphia eingespielt, mit dem Westminster Choir. Mutis Interpretation ist romantisch und ausdrucksstark sowie in entscheidenden Momenten sehr dramatisch. Das Spiel des Philadelphia Orchestra ist prächtig und fein nuanciert, der Chor singt ganz exzellent. Unter den Solisten sticht Jessye Norman sowohl vokal wie auch darstellerisch hervor. Der Tenor John Aller bietet eine zufriedenstellende Leistung, während Simon Estes darstellerisch völlig daneben liegt.

Mutis Aufnahme der Symphonie Fantastique mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra gehört zu den besten dieser Komposition von Hector Berlioz. Wie in so vielen Interpretationen dieser Sammlung ist es auch hier die Balance zwischen Drama und romantischer Gefühlswärme, die Muti besonders gut gelingt. Das Philadelphia Orchestra spielt spannungsvoll und mit virtuoser Brillanz, im langsamen Satz auch mit feiner Delikatesse.

Drei Werke von Ravel dirigiert Riccardo Muti auf einer CD, die er zusammen mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra aufgenommen hat: Boléro, Daphnis et Chloé (2. Suite) und Alborada del gracioso aus den Miroirs. So uninteressant, spannungslos, ja fast langweilig Mutis Boléro-Deutung auch ist, so faszinierend ist die 2. Suite aus Daphnis et Chloé. Es ist eine der stimmungsvollsten Interpretationen, die ich kenne, mit aufregenden Klangwirkungen. Dies gilt ebenfalls für die äußerst brillant dargebotene Orchesterfassung von Alborada del gracioso.

Riccardo Muti fasziniert uneingeschränkt mit einem phantastischen Spanienprogramm mit Chabriers Espana, de Fallas Dreispitz und Ravels Rhapsodie Espagnole, das zudem einen Triumph der Aufnahmetechnik darstellt: es ist dies eine absolut herausragende Digitalaufnahme, die Klangqualität ist sensationell! Nicht weniger begeisternd ist das Spiel des Philadelphia Orchestra, das Muti zu Spitzenleistungen führt.

Eine weitere CD vereint Ernest Chaussons Poème de l’amour et de la mer, Maurice Ravels Une Barque sur l’océan und Claude Debussys La Mer mit Waltraud Meier und dem Philadelphia Orchestra.

Auch wenn das Cover dieser Scheibe La Mer hervorhebt, ist zweifellos die erste halbe Stunde der Aufnahme die bemerkenswerteste. Waltraud Meier singt das Poème de l’amour et de la mer von Ernest Chausson absolut zauberhaft. Die beiden Gedichte sowie das Zwischenspiel verströmen einen extrem hohen Grad an Spannung, der uns in die Tiefen der Leidenschaft von Chausson, dem wagnerischsten aller französischen Komponisten, eintauchen lässt. Waltraud Meiers Stimme ist großartig, sehr natürlich trotz ihrer Ausdruckskraft. Das Orchester atmet perfekt mit der Solistin und unterstützt sie voll und ganz in ihrem Bemühen, diese Musik auf die eindrucksvollste Weise wiederzugeben. Während Riccardo Muti auch Une Barque sur l’océan mit großer dramatischer Kraft dirigiert, fehlt es La Mer auffallend an Vitalität und Raffinesse.

Die drei römischen Suiten Pini di Roma, Fontane di Roma und Feste Romana hat Muti 1984 mit dem Philadelphia Orchestra aufgenommen und sie sind entsprechend spektakulär und kontrastreich im Klang. Man hat die einzelnen Stücke allerdings bei anderen Dirigenten atmosphärischer gehört.

Chorwerke

Einen wichtigen Teil dieser Box machen diverse Chorwerke aus. Das geht vom Barock bis zum 20. Jahrhundert.

Magnificat und Gloria von Vivaldi auf einer Platte vereint durch Riccardo Muti, das ist ein Ereignis! Muti legt in diesen beiden modernen Interpretationen die großartige Klangphantasie von Vivaldi bloß. Sein untrüglicher Sinn für aufregende Klangwirkung lässt ihn die beiden Chorwerke spannungsvoll, mit viel Dynamik und einer höchst angebrachten federnden Lockerheit spielen. Von dem ausgezeichnet disponierten Kammerensemble des New Philharmonia Orchestra und von dessen exzellentem Chor (deren Natürlichkeit und Spiel- bzw. Klangfreude man hervorheben muss) wird Muti bestens unterstützt. Dass dabei noch Religiosität einfließt. ist auch wohl in erster Linie dem Dirigenten zu verdanken. Nicht weniger begeisternd als der Dirigent sind die beiden Solistinnen Teresa Berganza und Lucia Valentini-Terrani.

Mozarts Requiem dirigiert Riccardo Muti italienisch-lyrischem und mit breitem Atem. Neben den Berliner Philharmonikern und einem soliden, wenn auch nicht herausragenden Solisten-Quartett wirken der gute Schwedischen Radiochor mit. Im Vergleich aber zeigt es sich, dass andere Dirigenten mehr aus dem Mozart-Requiem gemacht haben.

Von Rossinis wohl schwierigstem Werk, dem Stabat Mater, legt Muti keine sehr gute Interpretation vor. Er zeichnet eher weiche Konturen, versucht Trauergefühle durch intimistische Gestaltung zu erreichen. Er bleibt damit in der Form klassisch, aber nicht besonders ausdrucksvoll. Giulini etwa, der damals gleichzeitig mit Muti eine Aufnahme präsentierte, weiß um die Gefahren, die dieses Stabat Mater birgt. Das Opernhafte kann nur durch Dramatik und durch Leidenschaftlichkeit in einen religiösen Ausdruck umgewandelt werden. Das mag paradox klingen, weil man annehmen könnte, gerade das Vermeiden von Dramatik führe weg von der Opernmusik. Das ist aber nicht der Fall, denn bei Muti klingt das Stabat Mater eher beiläufig, es plätschert galant dahin und wird so dem Inhalt der Texte einfach nicht gerecht. Im Übrigen hat Muti mit Catherine Malfitano, Agnes Baltsa, Robert Gambill und Gwynne Howell das schwächere Solistenquartett, in dem Gambill besonders unangenehm wirkt und die Baltsa ohne Zweifel die beste Leistung vollbringt.

Neben dem d-Moll-Requiem von Luigi Cherubini hat Cherubini-Spezialist Riccardo Muti auch das Requiem in c-Moll eingespielt. Der Dirigent weiß dem dramatischen, anspruchsvollen Werk Cherubinis zu bester Form zu verhelfen, d.h. es aufgrund seiner herrlichen Musikalität zu gestalten, ohne dadurch jedoch den religiösen Charakter zu zerstören. Sodann gelingt es Muti, eine ausgezeichnete Balance zwischen Orchester und Chor zu schaffen. Das Philharmonia-Orchester London wird aus seiner reinen Begleiterfunktion herausgeholt und durchaus mitgestalterisch eingesetzt. Dies wiederum hindert uns nicht daran, vor allem die Leistung des Chores hier zu würdigen. Die Ambrosian Singers sind mit, Leib und Seele dabei, singen, dass es eine wahre Freude für das Ohr ist.

Riccardo Muti dirigiert an der Spitze von Chor und Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks ebenfalls die Messa Solenne ‘Di Chimay’, eine wenig bekannte Messkomposition Cherubinis. Die Messe entstand in Chimay, wo Luigi Cherubini 1806 Zuflucht vom anstrengenden Leben des geplagten Opernkomponisten fand. Doch auch in Chimay wartete Arbeit auf ihn: der dortige Kirchenchor bestellte bei ihm eine Messe. Cherubini fand sich nach langem Zögern dazu bereit und schrieb, als wolle sich der Geist für die Abstinenz entschuldigen, eine große und besonders feierliche Orchestermesse, von der aber nur Kyrie und Gloria in Chimay uraufgeführt wurden. Er schrieb das Stück erst fertig, als er in das 200 Kilometer entfernt liegende Paris zurückgekehrt war. Riccardo Muti bringt die prachtvolle Komposition auf Hochglanz. Ein exzellenter Chor und ein sehr gutes und motiviertes Orchester unterstützen ihn dabei besser als die Gesangssolisten, von denen zumal Ruth Ziesak und Ildar Abdrazakov, wohl ungenügend vorbereitet und völlig unsouverän an ihre Aufgabe herangehen. Dennoch: das Stück und die Leistungen von Chor und Orchester machen aus dieser Aufnahme eine hoch willkommene Produktion.

In der Missa Solemnis in E, ebenfalls beim BR aufgenommen, gelingt Muti eine ansprechende Interpretation. Er pflegt den Klang, macht ihn sehr geschmeidig und schön, was zweifellos eine großartige Wirkung erzeugt. Der Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks ist dabei ein Juwel in des Meisters Hand, und auch das Orchester lässt sich zu einem runden und warmen Klang inspirieren. Die Solisten tun das übrige, um diese CD zu einer sehr gelungenen Aufnahme zu machen.

Ein absolutes Highlight dieser Muti-Box ist die Aufnahme der Quattro Pezzi Sacri von Giuseppe Verdi, 1982 live aufgenommen mit den Berliner Philharmonikern und dem Stockholmer Rundfunkchor sowie Eric Ericsons Kammerchor. Mutis Chorarbeit ist phänomenal, und die Mischung von Verinnerlichung und Dramatik ist optimal gelungen. Diese Aufnahme ist eine der wenigen Referenzaufnahmen dieser Kompositionen.

Verdis Requiem hat Muti zweimal für EMI (Warner) aufgenommen: Die erste davon, die Londoner, entstand 1979, also acht Jahre nachdem ich Muti im Verdi-Requiem in Florenz live erlebt hatte. In der Aufnahme mit dem Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus hat er seit 1971 unbestreitbar einen größeren Weg zurückgelegt. Wirkte er damals in Florenz noch unsicher, so haben sich seine Auffassungen in dieser Aufnahme gefestigt, er hat seiner Interpretation Form und vor allem Logik gegeben. Wenn er im Konzert kontinuierlich schnelle Tempi wählte, ist das in dieser Aufnahme nicht mehr der Fall. An einigen Stellen hat er auf ‘normal’ zurückgeschraubt, an anderen wiederum ist er wesentlich schneller geworden. Muti versucht nicht, die Opernhaftigkeit des Werkes mit Strenge und ständiger Sorge um Trauer zu verbergen. Er projiziert die Dramatik des Verdi-Requiems grell hinaus. Diese erste Aufnahme des Requiems hat aber auch Schwachpunkte. Denn wenn auch Philharmonia Orchestra und Chor aus London in der gewohnten Qualität musizieren und singen, kann das Solistenquartett das hohe Niveau nicht kontinuierlich halten. Am besten singen Jewgenij Nesterenko (obschon er etwas ausdrucksvoller sein könnte) und Agnes Baltsa. Die Baltsa ist stimmlich der beste Interpret in dieser Aufnahme. Ihre Merkmale: eine Technik, die sagenhaft ist, ein Ausdrucksvermögen, das unbegrenzt scheint und eine Stimme, die so viel Schönheit verströmt, dass man ein gewisses beglückendes Gefühl hat, immer wenn die Baltsa singt. Renata Scottos Leistung ist enttäuschend: In den Piani und Pianissimi ist sie ausgezeichnet, in den Forte-Passagen schreit sie fast, zudem wird ihre Stimme nach oben hin flach und unbiegsam. Enttäuschender aber noch ist Verano Lucchetti. Ihn wenigstens hätte Muti heimschicken sollen, denn seine Interpretation leidet sehr unter diesem Sänger. Er schreit und stemmt, dass einem fast übel wird.

Für seine zweite Aufnahme, 1987 live an der Mailänder Scala aufgenommen, hatte Muti einen hervorragend singenden Luciano Pavarotti zur Verfügung. Cheryl Studer ist zuverlässig, wenn auch, wie so oft, nicht besonders gut, aber mit Samuel Ramey und Dolora Zajic sind die tiefen Stimmen exzellent besetzt. Im Tempo ist Muti noch gemäßigter geworden, das Spirituelle wird stärker betont, und das ist wohl der große Unterschied zur ersten Aufnahme. Diese Mailänder Einspielung ist weniger dramatisch (aber nicht weniger kraftvoll), dafür aber viel lyrischer und verinnerlichter.

Zum Angebot im Vokalbereich gehört auch eine sehr gute, zum Teil feurige Aufnahme der Carmina Burana von Carl Orff, die 1979 in den Londoner Abbey Road Studios gemacht wurde, mit dem Philharmonia Orchestra und seinem herausragenden Chor sowie den exzellenten Solisten John van Kesteren, Jonathan Summers und Arleen Auger.

Orchesterauszüge aus Opern

Riccardo Muti ist ein anerkannter Spezialist von Verdi-Partituren, und seine Einspielungen von Verdi-

Opern bekamen von der Kritik höchstes Lob. Bemerkenswert ist in dieser Kollektion die CD ‘Opernballette von Verdi’. Neben den Muti-Gesamtaufnahmen entnommenen Auszügen aus Aida und Macbeth ist aus I Vespri Siciliani das Ballett Le Quattro Stagioni zu hören, das Muti gar glänzend musizieren lässt. Nicht weniger brillant, zum Teil sehr feurig, orchestral auf hohem Niveau ist die CD mit Verdi-Ouvertüren, aufgenommen mit dem New Philharmonia – Muti at his best.

Nun gibt es auch von Riccardo Muti eine Platte mit Rossini-Ouvertüren. Der Maestro hat aber davon seine eigenen Ideen. Das beginnt beim Programm: er verzichtet auf die Gazza Ladra und die Italiana in Algeri und dirigiert stattdessen II viaggio a Reims und L’assedio di Corinto. Und das endet mit Langeweile. Sei es nun die Scala di Seta, Guillaume Tell oder der Barbiere: durch Mutis Innovierungswillen wird so manches forciert, kehrt Gedankenschwere ein, die Rossini einfach nicht zu Gesicht stehen will.

BAROCK

Neben einer vorzüglichen, wenn auch mit großem Orchester und auf modernem Instrumentarium gespielten Fassung der Vier Jahreszeiten von Vivaldi gibt es eine schöne CD mit Trompetenkonzerten von Bach, Haydn, Telemann und Torelli, mit dem wie immer exzellenten Maurice André als Solist.

Die Interpretation von Händels drei Wassermusik-Suiten durch die Berliner Philharmoniker und Riccardo Muti stellt eine absolute Spitzenleistung dar. Der Stil Mutis ist verblüffend: ohne auch nur einen Augenblick lang in Melodienseligkeit oder ins Pathetisch-Feierliche abzugleiten, verleiht er dieser Musik die Opulenz dessen, was man sich heute im Idealfall unter höfischer Festmusik vorstellt. Bei üppigster Klangfülle und herrlichster Tongebung bleiben sämtliche thematische Linien bis ins Detail durchhörbar. Eine sorgfältige Differenzierung und Nuancierung, faszinierende Instrumentalleistungen vollenden den tiefen Eindruck, den diese Aufnahme hinterlässt, auch wenn wir die Musik heute anders zu hören gewohnt sind.

ZWEI NEUJAHRSKONZERTE

Wenn Melancholie, wie André Gide sagte, abgestorbene Inbrunst ist, muss Riccardo Muti ein glühender Verehrer der Melodien von Strauss und Co. sein. Auf jeden Fall ist in seinem Neujahrskonzert von 1997 ein sehr ausgeprägter Hauch von Melancholie zu spüren. Diese Melancholie, gemischt mit seiner sehr aristokratisch italienischen Sensibilität und Eleganz, beschert uns charmante Interpretationen, die sich sehr von dem unterscheiden, was derselbe Dirigent 1993 bei seinem Neujahrskonzert machte, wo sein Programm einen populäreren, ländlicheren Charakter hatte. Die Melancholie offenbart sogar in Franz von Suppés Cavallerie légère neue Aspekte. Diese Ouvertüre erschien übrigens damals zum ersten Mal auf dem Programm eines Neujahrskonzertes, zusammen mit neun anderen Werken, dem Motoren-Walzer, Carrière, Hofballtänze, Bluette, Die Bajadere, Leichtfüssig, Russischer Marsch, Dynamiden und Vorwärts. Wenn man die französische Polka Patronessen hinzufügt, die nie aufgenommen und 1945 zum letzten Mal gespielt wurde, kann man sagen, dass Muti dieses Mal innovativ ist.

Riccardo Muti war 1993 und 1997 der Dirigent der Wiener Neujahrskonzerte, und die Wiener Philharmoniker luden ihn erneut für ihr Konzert am 1. Januar 2000 ein. Dies zeigt wohl darauf hin, dass die Wiener den Italiener in diesem wienerischsten aller Repertoirebereiche sehr wohl zu schätzen wissen. 1997 hatte Muti neun Werke aufs Programm gesetzt, die zuvor nie in einem Neujahrskonzert gespielt wurden. 2000 waren es deren wohl nur fünf, aber das Programm beinhaltete doch auch viele selten gespielte Stücke, so dass wieder einmal ein exquisites Konzert zustande kam, das Muti mit viel Sensibilität und einer sehr italo-aristokratisch wirkenden Eleganz zu einem sorglos-schwungvollen Potpourri werden lässt. 1993 war das Ländlich-populäre ein Charakteristikum des Muti-Neujahrskonzerts. 1997 wirkte er sehr melancholisch und 2000 machte er ganz in Charme und gute Laune, freilich ohne Üppigkeit, ganz Muti halt.

Like many of his colleagues, Italian conductor Riccardo Muti, who turns 80 at the end of July, has recorded for many labels, EMI, Deutsche Grammophon, Sony and most recently Chicago’s CSO Resound. Warner is now issuing Muti’s orchestral recordings from EMI.

WORKS BY TCHAIKOVSKY

Riccardo Muti is an excellent Tchaikovsky conductor. He has proven it in his recordings of individual symphonies, though never as overtly as in the recording of the Manfred Symphony, where the conductor delivers a magnificent performance. His interpretation is full of tension, has a character and expressiveness like no other, it is dramaturgically effective but never superficial, it is full and well-proportioned in sound, excellently blended and yet audible down to the smallest detail. The music flows broadly, with the aforementioned effects remaining embedded in the symphonic flow. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s playing is of the highest quality, as is the recording in its purely technical aspects.

Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony, the Little Russian, contains many elements of Russian folklore. Muti provides the right dosage, although he emphasizes symphonic brilliance more than Rostropovich or Kitajenko, whose interpretations are undoubtedly more ‘Little Russian’ than those of Riccardo Muti, who fires up the Philharmonia Orchestra to a terrific performance. However, even before the interpretation of the Second Symphony, the conductor manages to get the listener on his side. Indeed, beforehand, the Fantasy Overture Romeo and Juliet provides an excellent moment. The conductor tells the unhappy love story sensitively, expressing love, passion and struggle with a lot of effective contrasts.

Tchaikovsky’s Third is a recording that could be used to excite even those people for this work who otherwise only listen to Symphonies 4 through 6. Muti builds up the introduction with tension, prepares misterioso the Allegro which Tchaikovsky wants ‘brillante’, and which, with Muti, becomes explosively brilliant. The slow movements have a great deal of feeling, the Scherzo has power, and the final Polonaise concludes the work in a hymn-like, even apotheosis-like manner. The Philharmonia Orchestra, audibly blossoming under Muti’s conducting, plays enthusiastically.

In Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony, also with the Philharmonia Orchestra London, the maestro takes a bit longer to really warm up, but already the second half of the first movement can inspire. Muti also manages a very compelling second movement, which is significantly enhanced as a result. It is marvelous how he brings out the flute in this movement and makes the woodwinds stand out in general. Muti has also succeeded very charmingly in the playful scherzo. The last movement is also great, intoxicating, and ecstatic.

After an excellent interpretation of the Fifth, Riccardo Muti concludes his recording of the Tchaikovsky symphonies with the Sixth, the Pathétique. His interpretation is not only one more among the longer ones, it is one of the best of them. Muti’s normally great passion becomes ecstatic and sometimes even wild. He drives the orchestra like no other, powerful, poignant, and completely transports the listener into the frenzy of Tchaikovsky’s music. Not for a moment does he let the tension drop. He provides a cohesive expressive interpretation that is greatly aided by the glorious playing of the London Philharmonia Orchestra.

Muti’s interpretation of the Tchaikovsky ballets is spectacular, solemn, rather broad, always close to the action, and therefore justifiable in all its forms. The sound is luxurious, and the Philadelphia orchestra shines and excels in both suites. Actually, the ear can wish for nothing more beautiful: through the action-based interpretation, the eye sees through the ear!

Muti recorded Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto with soloist Andrei Gavrilov and the Philharmonia Orchestra London. Gavrilov conceives the piano part very weightily, but without making it sound broad. Nor is it overly pathetic. Muti not only accompanies very attentively, he also reshapes many a passage, coloring very strongly and seasoning the sound quite solidly. Both emphasize – and Gavrilov does it with a very interesting color gradient – the maestoso of the first movement. Admittedly, I would have liked the Allegro con spirito to be a bit more exciting. The Andantino has a very slow pace and contrasts sharply with the Prestissimo of the 2nd movement, which, like the concluding Allegro con fuoco, shows a lively and very present playing by the soloist. On the whole, however, this is not a recording for the top field.

Another Tchaikovsky disc contains the 1812 Overture and the String Serenade, a program that at first glance seems incongruous, but which, as Muti sees it, goes together perfectly. For Muti’s 1812 is not a gaudy war drama, but rather a musical indictment of war, ‘un sombre tableau,’ as the French would say. The conductor approaches the work with a great deal of passion and even more feeling, giving it a meaningful expressiveness that one does not otherwise hear in 1812. Even at the end he avoids the spectacular, which is why the musical events then even take on grotesque features. Since the first movement of the string serenade immediately follows the so unceremoniously played Overture Solennelle, it takes on almost religious traits, as if it were a declaration of peace. The second movement also lacks the outward elegance that is usually inherent in it. Instead, it shows a great deal of inner grace. The third movement sounds restrained, almost fervent. Finally, in the fourth, the atmosphere changes only very slowly, until the work ends in a joyfully moving conclusion.

OTHER RUSSIAN COMPOSERS

Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, as orchestrated by Maurice Ravel, is a piece that lends itself perfectly to demonstrating the technical playing qualities of an orchestra. The musicians of the Philadelphia Orchestra, in their blend of power, brilliance, and brightness, bring the best qualifications to make the Pictures score exciting. And Muti exploits this skill to exhaust Ravel’s sound world, delivering what is actually also a very French interpretation of the Pictures. Through an exceedingly close attention to detail, the breadth of musical thought and imagination is fully expressed. Muti shapes the work from a sovereign inner calm, without any pathos. This results in an intense but never ecstatic performance of vivid eloquence that occupies an important place in the discography. The orchestra is also brilliant in A Night on the Bare Mountain.

Philadelphia also produced the recording of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. Muti again succeeds in a great mixture of sensuality, oriental lushness and brilliant rhythm. Some finely worked out orchestral details are also interesting.

At the helm of the Philadelphia Orchestra Riccardo Muti delivers a rhythmically gripping, almost vehement version of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps. A top notch performance!

And then there are Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet Suites, which Muti breathes life into. Oh, what emotions are exuded, how pulsating is this music! Muti conducts the suites with southern temperament, passion and ardor. Even without knowing the program sequence, the listener can effortlessly situate each part of the suites. The Philadelphia Orchestra performs a tour de force of precision and virtuosity.

No less outstanding are the recordings of Prokofiev’s Ivan the Terrible in the arrangement by Abram Stasevich and the Sinfonietta. Muti’s conducting is powerful and exciting, suitably dramatic with great climaxes. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s playing is brilliant, and the soloists, especially Irina Arkhipova and Anatoly Mokrenko, are superb.

A great moment in the history of recordings – this is how we must describe Riccardo Muti’s recording of Stravinsky’s ballet suite Petrouchka. With Muti the composition gains in a fascinating way in colorfulness, in luminous power, in rhythmic hardness and gripping depth. This interpretation also captivates with its flexible shaping, greater dynamic freedom and a strong differentiation of the orchestral sound, whose liveliness, inner tension and outer nervousness is hardly matched by any other conductor. Riccardo Muti knows what Stravinsky’s music lives on! And the Philadelphia Orchestra has fully grasped it.

Muti recorded Rachmaninov’s Concertos for Piano and Orchestra Nos. 2 & 3 and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with Andrei Gavrilov and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1986 and 1989. Gavrilov’s playing is virtuosic and sensitive, beautiful in tone throughout, and he is supported by a passionately breathing Muti and the phenomenal Philadelphia Orchestra. The slow movements in particular are evocatively beautiful.

The complete recording of the three Scriabin symphonies with the Philadelphia Orchestra is a milestone in the discography of these compositions.

Orchestrally balanced, they impress with a rich and sonorous sound. Muti invests himself fully in this composer, and he draws level with Abbado, but arguably falls a smidge short of the recording of Svetlanov and especially Dmitrij Kitajenko, which is more authentic in their Russian character.

In Riccardo Muti’s discography, Shostakovich is not a much recorded composer. There is a good recording of the 13th Symphony with the Chicago Symphony on CSO Resound, and this collection includes a recording of the Fifth with the Philadelphia Orchestra. It is impressive at best because of the orchestra’s superb playing; the brass section of the American orchestra in particular makes a phenomenal contribution to the sound. But Muti doesn’t really penetrate the music, delivering a polished, superficial interpretation that misses the bitterness and intensity of the emotions. The way he approaches Shostakovich is more suited to the Festive Overture, which figures as a filler on this CD.

DVORAK & BRUCKNER

The effective timpani beats in the first movement of Antonin Dvorak’s 9th Symphony (From the New World) and the daring tempo changes initially raise eyebrows. But as the movement progresses, the conductor calms down somewhat, and the second movement succeeds beautifully and lyrically, but in the scherzo and finale there are again distracting antics that make this interpretation mannered.

A reference recording of Antonin Dvorak’s Violin Concerto is presented by Muti and Kyung-Wha Chung together with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Both combine spiritedly gripping and delicately tender music-making on the one hand and thus deliver a passionately gestural interpretation that could not be more beautiful and fulfilling.

GERMAN-AUSTRIAN SYMPHONIC MUSIC

The three M-recording – Mozart, Mutter, Muti – was duly singled out from the normal production by EMI at the time: it is indeed a special recording. Anne-Sophie Mutter plays Mozart’s Violin Concertos Nos. 2 and 4 with a fervor that makes one’s heart beat faster. Technically, Mutter is even more perfect than Oistrakh. And while we are comparing: what the violinist Oistrakh and the conductor Oistrakh could not achieve in one person, namely homogeneous and coordinated playing of the solo violin and the orchestra, Riccardo Muti with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Anne-Sophie Mutter achieve in a congenial manner. This emotional expression is quite unpretentious, but the interplay between the soloist and the orchestra is enchanting, with a rare expressivity that neither Oistrakh nor Menuhin (also conductor and soloist) achieved.

Svjatoslav Richter is the soloist in Mozart’s 22nd Piano Concerto, K. 482, recorded in 1979 with the Philharmonia Orchestra. It is a particularly powerful interpretation, clearly pointing in the direction of Beethoven, which Muti also allows to be very contrasted and powerfully contoured with the orchestra. It is interesting that Richter plays Benjamin Britten’s cadenzas, which the latter composed for the Russian pianist and which provide a deliberately strong contrast in the concerto.

No less fresh and powerful are the 24th Symphony K. 182, the 25th K. 183 and the 29th K. 201 (with the New Philharmonia). The recording of the Jupiter Symphony made with the Berlin Philharmonic is very balanced, vital and colorful.

The complete recording of the Beethoven symphonies with the Philadelphia Orchestra is surprising, as Riccardo Muti plays with tempos in an almost ideal way, giving the music time and space to unfold. Muti’s interpretation is classically beautiful, rich in nuances, basically also very lyrical and always significant in gestures. This is particularly evident in the 3rd movement of the consistently excellent 9th Symphony, which Muti makes sing with emotion.

Muti recorded an exceedingly serene, idyllic version of Beethoven’s 6th Symphony, the Pastorale, with the Philadelphia Orchestra. With infinite attention to small, picturesque details, as if he really wanted to trace Beethoven’s image of nature with every note, Muti succeeds in an interpretation that is distinguished by its quiet beauty.

In addition there is the Piano Concerto No. 3 with Svjatoslav Richter as soloist as well as 3 overtures by Beethoven, Leonore No. 3, The Consecration of the House and the Fidelio Overture. I am aware that the famous Russian pianist had already recorded Beethoven’s Third Concerto in 1960 in Vienna with Kurt Sanderling as conductor for DGG, and this recording also stands out from the overabundance. In both cases Richter plays the composer’s original cadenza in the first movement so impressively that it almost takes one’s breath away.

Muti recorded the Schubert symphonies with the Vienna Philharmonic. He conducts them briskly and with vitality, but differentiates them very well, so that he succeeds in very characterful interpretations. The overture and incidental music to Rosamunde, which Muti approaches quite theatrically, are delightful. The Vienna Philharmonic follows him attentively in his reference-rich conducting, and this results in an interpretation that puts others, more non-committal, in the shade.

There is a good coupling of works with Schumann’s Symphony No. 1 (Spring Symphony), and Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 5 (Reformation Symphony). The way Muti conducts the Spring Symphony is very interesting. With him, it sprouts more than is usually heard; his springtime emotions are more stirring than those of other conductors. This is a jubilant, a storming and an urging interpretation that compellingly carries one along, overwhelmed by its musical-melodic richness, but also by the intimacy of feeling, for example in the second movement. There are also 31 minutes and 40 seconds of wonderful music with the Mendelssohn Symphony. Muti succeeds in some very exciting climaxes. He does not celebrate the work, he conducts it with tremendous drama. The other symphonies, the Second, Third and Fourth (coupled with an elegant Italian by Mendelssohn) also feature urgent and fluid, bright-toned and brilliant music-making by London’s New Philharmonia.

Schumann’s Violin Concerto gets under your skin. It is idiosyncratically shaped and contains a fair amount of accentuation that Schumann did not envision: Gidon Kremer, Riccardo Muti and the Philharmonia Orchestra wanted to get what they could out of this difficult work.

Muti and his soloist also worked congenially on Sibelius’ Violin Concerto. Here, too, one is pleased with excellent, exciting orchestral playing and a solo part extremely rich in ideas.

Riccardo Muti and Alexis Weissenberg approach the First Piano Concerto by Johannes Brahms not in a superficially expressive manner, but by deeply exploring all areas of human feeling. The result is commendable. There is thoughtful lingering, stressed rushing past, there is power and powerlessness, calm and restlessness: rarely have performers brought out the contrasts in this concerto like this. Muti’s account (with the Philadelphia Orchestra) is excellent, and Weissenberg’s playing is surprising for its clarity, its ‘order’ and the manner in which it blends into the orchestra.

Muti has recorded Bruckner’s Symphonies Nos. 4 and 6 with the Berlin Philharmonic. In both works, he is primarily interested in the orchestral textures and what can be expressed dramatically with them, and even more so in what an Italian and an opera conductor can get out of these scores in terms of vocal melodicism. It goes without saying that this procedure also serves the climaxes in the best possible way. This results in two extremely dynamic and passionate Bruckner recordings that definitely have their place in the discography, not least because of the brilliant music-making of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Franz Liszt’s Faust Symphony and Les Préludes are united in an album, recorded by the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra conducted by Riccardo Muti.

Muti has again achieved something quite magnificent with these recordings. He completely reshapes Les Préludes dramaturgically, and breathes life into the music, which is often sublimely pathetic.

And Riccardo Muti follows the same recipes in the Faust Symphony – which is actually nothing more than a series of three tone poems on the themes of Faust, Gretchen and Mephisto. With a resolute search for dramatic sequences that are meant to recall the plot, with all the motifs and emotional moments associated with it he gets a superb result. The musicians from Philadelphia follow their conductor, despite his sometimes furious tempi, in brilliant disposition and with remarkable commitment.

In his introductory text, Michael Kennedy calls Mahler’s First Symphony a symphonic drama about nature and young love. An apt description, at least for Riccardo Muti’s warm, buoyant interpretation overflowing with positive, gratifying feelings. Muti not only conveys this nature-loving, spring-awakening feeling of joy, of happiness, he also takes care of the effects that were so dear to Mahler’s heart; he cares for abundant colors, works out instrumental effects in one completely delightful recording. And then: what a magnificent orchestra! What an impressive wind section! What string corps! What outstanding woodwinds! What suppleness! What sound!

FRENCH AND ITALIAN COMPOSERS

Muti recorded several works by French composers, including the Symphony by César Franck. He did not succeed in a particularly coherent and certainly not a typically French interpretation, but he did work with the Philadelphia Orchestra on the textures of the music in a not uninteresting way, which then always makes one sit up and take notice.

Roméo et Juliette by Berlioz was recorded in Philadelphia, with the Westminster Choir. Muti’s interpretation is romantic and expressive as well as very dramatic at crucial moments. The playing of the Philadelphia Orchestra is splendid and finely nuanced, and the chorus sings quite excellently. Among the soloists, Jessye Norman stands out both vocally and in performance. Tenor John Aller offers a satisfying performance, while Simon Estes is completely disappointing.

Muti’s recording of the Symphonie Fantastique with the Philadelphia Orchestra is among the best of this composition by Hector Berlioz. As in so many interpretations of this collection, it is the balance between drama and romantic warmth of feeling that Muti manages particularly well. The Philadelphia Orchestra plays with tension and virtuosic brilliance, and in the slow movement also with fine delicacy.

Riccardo Muti conducts three works by Ravel on a CD that he recorded together with the Philadelphia Orchestra: Boléro, Daphnis et Chloé (2nd Suite) and Alborada del gracioso from the Miroirs. Muti’s Boléro interpretation is uninteresting, tensionless, almost boring, but the one of the Second Suite from Daphnis et Chloé is fascinating. It is one of the most atmospheric interpretations I know, with exciting sound effects. This is also true of the extremely brilliantly performed orchestral version of Alborada del gracioso.

Riccardo Muti fascinates unreservedly with a fantastic Spain program with Chabrier’s Espana, de Falla’s Three-cornered Hat and Ravel’s Rhapsodie Espagnole. This is a triumph of recording technology, and the sound quality is sensational! No less inspiring is the playing of the Philadelphia Orchestra, which Muti leads to top performances

Another CD brings together Ernest Chausson’s Poème de l’amour et de la mer, Maurice Ravel’s Une Barque sur l’océan and Claude Debussy’s La Mer with Waltraud Meier and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Although the cover of this disc highlights La Mer, it is undoubtedly the first half hour of the recording, which is the most remarkable. Waltraud Meier singing in the Poème de l’amour et de la mer by Ernest Chausson is absolutely magical. The two poems, as well as the interlude, exude an extremely high degree of tension that immerses us in Chausson’s depths of passion. Waltraud Meier’s voice is magnificent, very natural despite its expressiveness. The orchestra breathes perfectly with the soloist, fully supporting her efforts to render this music in the most impressive way. While Riccardo Muti also conducts Une Barque sur l’océan with great dramatic power, La Mer is conspicuously lacking in vitality and refinement.

Muti recorded the three Roman suites Pini di Roma, Fontane di Roma and Feste Romana with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1984 and they are appropriately spectacular and contrasting in sound. Yet, the have become more atmospheric with other conductors.

CHORAL WORKS

An important part of this box is made up of various choral works ranging from the Baroque to the 20th century.

The Magnificat and Gloria by Vivaldi united on one disc are outstanding. Muti emphasizes Vivaldi’s magnificent imagination in these two modern interpretations. With his unerring sense for exciting sound effects, a lot of dynamics and a highly appropriate flexibility the two choral works become truly exciting. Muti is supported in the best possible way by the excellently disposed chamber ensemble of the New Philharmonia Orchestra and by its excellent choir (whose naturalness and enthusiasm must be emphasized). No less inspiring than the conductor are the two soloists Teresa Berganza and Lucia Valentini-Terrani.

Riccardo Muti conducts Mozart’s Requiem with Italian lyricism and broad breath. In addition to the Berlin Philharmonic and a solid, but not outstanding quartet of soloists, the good Swedish Radio Choir is a valuable partner in this recording. In comparison, however, it is evident that other conductors have made more of the Mozart Requiem.

Muti presents a not so good interpretation of Rossini’s probably most difficult work, the Stabat Mater. He draws rather soft contours, tries to achieve feelings of mourning through intimate playing. He thus remains classical in form but not particularly expressive. Giulini, for example, who presented a recording at the same time as Muti, knows the dangers of this Stabat Mater. The operatic quality can only be transformed into a religious expression through drama and through passion. But this is not the case, because with Muti the Stabat Mater sounds rather incidental, it ripples along gallantly and thus simply does not do justice to the content of the texts. Muti has also the weaker quartet of soloists with Catherine Malfitano, Agnes Baltsa, Robert Gambill and Gwynne Howell. Gambill is particularly unpleasant and Baltsa is without doubt the best performer.

In addition to Luigi Cherubini’s Requiem in D minor, Cherubini specialist Riccardo Muti has also recorded the Requiem in C minor. The conductor knows how to help Cherubini’s dramatic, demanding work to its best form, i.e. to shape it on the basis of its splendid musicality, but without thereby destroying its religious character. Muti then succeeds in creating an excellent balance between orchestra and chorus. The Philharmonia Orchestra of London is taken out of its purely accompanimental function and is definitely used in a co-creative way. This, in turn, does not prevent us from paying particular tribute to the performance of the chorus here. The Ambrosian Singers are in it with heart and soul, singing that it is a true joy for the ear.

Leading the Bavarian Radio Choir and Symphony Orchestra, Riccardo Muti also conducts the Messa Solenne ‘Di Chimay,’ a little-known composition by Cherubini. The mass was composed in Chimay, where Luigi Cherubini found refuge from the strenuous life of the harried opera composer in 1806. But work was also waiting for him in Chimay: the church choir there commissioned a mass from him. After much hesitation, Cherubini agreed and, as if to apologize for his abstinence, wrote a large and particularly solemn orchestral mass, of which only the Kyrie and Gloria were premiered in Chimay. He did not finish writing the piece until he returned to Paris, 200 kilometers away. Riccardo Muti brings this magnificent composition to a high gloss. An excellent choir and a very good and motivated orchestra support him better than the vocal soloists, of whom Ruth Ziesak and Ildar Abdrazakov, in particular, were probably insufficiently prepared. Nevertheless, the piece itself and the performances by the chorus and orchestra make this recording a most welcome production.

In the Missa Solemnis in E, also recorded in Munich, Muti manages an appealing interpretation. He cultivates the sound, making it very supple and beautiful, which undoubtedly creates a great effect. The Bavarian Radio Choir is a jewel in the master’s hand, and the orchestra is also inspired to produce a round and warm sound. The soloists do the rest to make this CD a very successful recording.

An absolute highlight of this Muti box is the recording of Giuseppe Verdi’s Quattro Pezzi Sacri, recorded live in 1982 with the Berlin Philharmonic, the Stockholm Radio Choir and Eric Ericson’s Chamber Choir. Muti’s choral work is phenomenal, and the blend of internalization and drama is ideally achieved. This recording is one of the few reference recordings of these compositions.

Muti has recorded Verdi’s Requiem twice for EMI (Warner): The first of these, the London one, was made in 1979, eight years after I saw Muti live in Florence in the Verdi Requiem. In the recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus, he has undeniably come a long way since 1971. If he seemed uncertain then in Florence, in this recording his perceptions have firmed up, he has given form and, above all, logic to his interpretation. If he continuously chose fast tempi in the concerto, that is no longer the case in this recording. In some places he has cut back to ‘normal’, in others he is much faster. Muti does not try to hide the operatic nature of the work with austerity and constant concern for sadness. He projects the drama of Verdi’s Requiem glaringly. This first recording of the Requiem has its weak points, however. For though the Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus of London make music and sing with their usual quality, the quartet of soloists cannot continuously maintain the high level. The best singers are Yevgeny Nesterenko (although he could be a bit more expressive) and Agnes Baltsa. Baltsa is vocally the best performer in this recording. Her characteristics: a technique that is fabulous, an expressiveness that seems unlimited, and a voice that exudes so much beauty that one has a certain delighted feeling whenever the Baltsa sings. Renata Scotto’s performance is disappointing. She is excellent in the piani and pianissimi, but in the forte passages she almost screams; moreover, her voice becomes flat and inflexible towards the top. Even more disappointing, however, is Verano Lucchetti. Him, at least, Muti should have sent home, for his interpretation suffers greatly from this singer.

For his second recording, made live at La Scala in Milan in 1987, Muti had a superbly singing Luciano Pavarotti at his disposal. Cheryl Studer is reliable, though, as so often, not particularly good, but with Samuel Ramey and Dolora Zajic the lower voices are excellent. In tempo Muti has become even more moderate, the spiritual side is more emphasized and this is probably the big difference from the first recording. This Milan recording is less dramatic (but no less powerful), but much more lyrical and introverted.

The vocal recordings also include a very good recording, some of it fiery, of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, made at London’s Abbey Road Studios in 1979, with the Philharmonia Orchestra and its outstanding chorus, and excellent soloists John van Kesteren, Jonathan Summers, and Arleen Auger.

ORCHESTRAL EXCERPTS FROM OPERAS

Riccardo Muti is a recognized specialist of Verdi scores, and his opera recordings have received the highest praise. In this collection the CD ‘Opera Ballets by Verdi’ is particularly worthwhile. In addition to excerpts from Aida and Macbeth taken from Muti’s complete recordings, he conducts a brilliant performance of the ballet Le Quattro Stagioni from I Vespri Siciliani. No less brilliant, in part very fiery, orchestrally on a high level is the CD with Verdi overtures, recorded with the New Philharmonia – Muti at his best.

Now there is also a disc of Rossini overtures by Riccardo Muti. The maestro, however, has his own ideas about them. It starts with the program: he does without the Gazza Ladra and the Italiana in Algeri and conducts II viaggio a Reims and L’assedio di Corinto instead. And that ends in boredom. Be it Scala di Seta, Guillaume Tell or the Barbiere: Muti’s will to innovate forces some things, brings in a weightiness of thought that is simply not to Rossini’s liking.

BAROQUE

In addition to an excellent version of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, albeit played with a large orchestra and on modern instruments, there is a fine CD of trumpet concertos by Bach, Haydn, Telemann and Torelli, with the outstanding Maurice André as soloist.

The interpretation of Handel’s three Water Music suites by the Berlin Philharmonic and Riccardo Muti represents an absolute top performance. Muti’s style is astounding: without slipping for a moment into melodiousness or the pathetically solemn, he imbues this music with the opulence of what today is ideally thought of as courtly festive music. With the most luxuriant sonority and the most splendid tone, all thematic lines remain audible down to the last detail. Careful differentiation and nuance, fascinating instrumental performances complete the deep impression left by this recording, even if we are used to hearing the music differently today.

TWO NEW YEAR CONCERTS

If melancholy is, as André Gide said, dead fervor, Riccardo Muti must be an ardent admirer of the melodies of Strauss and company. In any case, there is a very pronounced air of melancholy in his 1997 New Year’s Concert. This melancholy, mixed with his very aristocratic Italian sensibility and elegance, gives us charming interpretations that are very different from what the same conductor did in his 1993 New Year’s Concert, where his program had a more popular, rural character. Melancholy reveals new aspects even in Franz von Suppé’s Cavallerie légère. This overture appeared for the first time on the program of a New Year’s concert, along with nine other works, the Motoren Waltz, Carrière, Hofballtänze, Bluette, Die Bajadere, Leichtfüssig, Russian March, Dynamiden, and Vorwärts. Add the French polka Patronessen, never recorded and played for the last time in 1945, and you can say that Muti is innovative this time.

Riccardo Muti was the conductor of the Vienna New Year’s Concerts in 1993 and 1997, and the Vienna Philharmonic invited him again for 2000. This probably indicates that the Viennese hold the Italian in high esteem in this most Viennese of repertoire areas. In 1997 Muti had put nine works on the program that had never before been played in a New Year’s concert. This year there were only five, but the program also included many rarely played pieces, so that once again an exquisite concert came about, which Muti turned into a carefree, swinging potpourri with a great deal of sensitivity and a very Italian-aristocratic elegance. In 1993, the rustic-popular was a characteristic of Muti’s New Year’s concert. In 1997 he seemed very melancholic, and in 2000 Muti went all in charm and good humor, admittedly without opulence.

Beethoven: Symphonien Nr. 1-9 + Nr. 6 & 7 + Klavierkonzert Nr. 3 + Ouvertüren Fidelio, Leonore Nr. 3, Die Weihe des Hauses-Ouvertüre op. 124; Andante favori WoO 57; Mozart: Symphonien Nr. 24, 25, 29, 41 + Divertimento KV 136 + Klavierkonzert Nr. 22 + Violinkonzerte Nr. 2 & 4 + Requiem KV 626 + Ave verum KV 618; Schubert: Symphonien Nr. 1-9 + Rosamunde (Ouvertüre & Ballettmusik); Schumann: Symphonien Nr. 1-4 + Violinkonzert d-Moll op. posth. + Hermann und Dorothea op. 136 + Die Braut von Messina op. 100; Mendelssohn: Symphonien Nr. 3-5 + Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt-Ouvertüre op. 27; Brahms: Klavierkonzert Nr. 1; Bruckner: Symphonien Nr. 4 & 6; Mahler: Symphonie Nr. 1; Liszt: Faust-Symphonie; Les Préludes; Dvorak: Symphonie Nr. 9 + Violinkonzert op. 53; Tchaikovsky: Symphonien Nr. 1-6 + Symphonien 4-6 + Manfred-Symphonie op. 58 + 1812-Ouvertüre op. 49 + Francesca da Rimini op. 32 + Hamlet-Ouvertüre op. 67 + Klavierkonzert Nr. 1 + Romeo & Julia-Ouvertüre + Streicherserenade op. 48 + Dornröschen-Suite op. 66a + Schwanensee-Suite op. 20a; Rachmaninov: Klavierkonzerte Nr. 2 & 3 + Paganini-Rhapsodie op. 43; Prokofiev: Iwan der Schreckliche-Filmmusik op. 116 + Sinfonietta op. 48 + Romeo & Julia-Suiten Nr. 1 & 2; Shostakovich: Symphonie Nr. 5 + Festouvertüre op. 96; Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique op. 14 + Roméo et Juliette op. 17 + Rossini: Stabat Mater; Guillaume Tell-Ouvertüre + Ouvertüren Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Il Viaggio a Reims, L’Assedio di Corinto, La Scala di Seta, Semiramide; Cherubini: Requiem c-Moll à la Memoire de Louis XVI + Requiem d-Moll für Männerchor & Orchester + Messe A-Dur dell’Incoronazione + Messa solenne per il Principe Esterhazy + Messa solenne G-Dur per l’Incoronazione di Luigi XVIII + Missa solemnis E-Dur + Marche religieuse + Motetten Antifona sul canto fermo 8. tona & Nemo gaudeat; Verdi: Requiem (2x) + Quattro Pezzi sacri + Orchesterstücke aus Aida, I Vespri siciliani, La Battaglia di Legnano, La Forza del Destino, Luisa Miller, Macbeth, Nabucco; Ravel: Alborada del gracioso + Boléro + Daphnis et Chloé-Suite Nr. 2 + Rhapsodie espagnole + Une Barque sur l’Océan; Debussy: La Mer; Stravinsky: Der Feuervogel-Ballettsuite + Le Sacre du Printemps + Petruschka; Sibelius: Violinkonzert op. 47; Respighi: Pini di Roma + Fontane di Roma + Feste romane; Mussorgsky: Bilder einer Ausstellung; Chabrier: Espana; Franck: Symphonie d-Moll + Le chasseur maudit; de Falla: Der Dreispitz-Ballettsuiten Nr. 1 & 2; Orff: Carmina burana; Scriabin: Symphonien Nr. 1-3 + Prometheus op. 54; Rimsky-Korssakov: Scheherazade op. 35; Vivaldi: Le Quattro Stagioni + Konzert RV 570 für Flöte, Fagott, Streicher, Bc La Tempesta di Mare + Flötenkonzert RV 439 « La Notte »; Gloria RV 589; Magnificat RV 611; Bach: Brandenburgisches Konzert Nr. 2; Händel: Wassermusik-Suiten Nr. 1-3 HWV 348-350; Haydn: Trompetenkonzert Es-Dur H7e Nr. 1; Telemann: Trompetenkonzert D-Dur TWV 51: D7; Torelli: Trompetenkonzert D-Dur G. 28; Neujahrskonzert Wien 1997 +Neujahrskonzert Wien 2000; Dokumentation Muti and the Philharmonia – A Legendary Era;