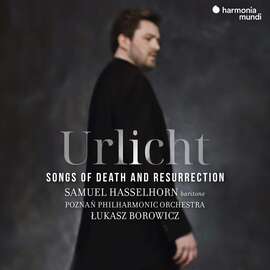

Dies ist eine bemerkenswerte CD, nicht nur wegen des wie erwartet herausragenden Gesangs von Samuel Hasselhorn, sondern auch wegen des Dirigenten Lukasz Borowicz. Dass ich ihn hochschätze, habe ich in einer langen Reihe von Rezensionen kundgetan. Doch das, was er in diesem Programm mit dem Poznan Philharmonic an Klang produziert, ist phänomenal. In keiner mir bekannten Aufnahme passiert in Mahlers Revelge im Orchester so viel wie man in dieser Einspielung hören kann. Das ist das ganze Mahler-Theater, die klangliche Wunderkammer in vollem Ausmaß! Aber nicht nur das: Im Urlicht umkleidet das Orchester die Stimme perfekt und bringt sie zusammen mit dem Instrumentalen zu optimaler Wirkung, weil die Musik vervollständigt wird.

Und die Stimme von Haselhorn ist in diesem Recital nicht weniger faszinierend, sein Gesang ist darstellerisch packend, mit farblichen und dynamischen Nuancen und einer prägnanten Textdarstellung.

Revelge ist bei ihm nicht nur dramatisch, es ist voller Unerbittlichkeit, die den inneren Zwang des Marschierens drastisch hörbar werden lässt, ohne Rücksicht auf Verluste. Borowicz verstärkt mit dem Orchester diesen gedankenlosen Zwang, der auch die Gebeine in Reih und Glied marschieren lässt.

Engelbert Humperdincks ‘Verdorben! Gestorben!’ aus der Oper Königskinder ist nicht weniger packend, weil Hasselhorn sehr einfühlsam singt und Borowicz das Rhapsodische der opulenten Orchesterbegleitung mitteilsam und evokativ werden lässt.

Ganz andere Klangwelten bieten sich dem Hörer in Pierrots Tanzlied aus Korngolds Die Tote Stadt an, in der sich der Charme und die Verbitterung Pierrots in Hasselhorns lyrischem Gesang ideal verbinden, um uns das Schicksal dieses Clowns mitfühlen zu lassen.

Was sich uns dann in Mahlers Mitternachtsgesang präsentiert, ist einmal mehr Extraklasse, weil Borowicz die Stimme mit wunderbar präsentem und farbenreichem Orchester in eine Luxusschatulle legt. Im Vergleich klingen Hampson und Bernstein schon fast pathetisch und manieriert.

Hasselhorn singt dem Tod sehr gefasst und ohne Larmoyanz geradezu positiv und heroisch entgegen, umgeben von einem farbig-grandiosen Orchesterklang, wie man ihn in dieser Rhetorik noch nicht oft vernommen hat, weder bei Karajan noch bei Thielemann und Boulez: nirgends ist die Symbiose von Stimme und Orchester so perfekt wie in dieser Einspielung.

Das gilt auch in dem absolut phänomenalen und spannenden Erlkönig-Vertonung ‘Herr Oluf’. Danach klingt Mahlers Urlicht in einer von Natürlichkeit und Ehrlichkeit geprägten Interpretation umso berührender.

In Alexander von Zemlinskys Altem Garten blüht alles auf in der extremen Chromatik der Musik, und die faszinierende Orchestrierung mit den wunderschön verwobenen Gesangslinien lässt dieses Lied nicht zuletzt auch durch die fantasievolle und stimmlich großartige Darbietung von Hasselhorn ins Schöne transzendieren.

Große Romantik ist dann in Braunfels’ Beschreibung eines Soldatengrabs zu hören, die extrem kontrastreich wirkt gegenüber dem Duett von Marie und Wozzeck in Bergs Oper, das einen surrealen Charakter bekommt. Aber Marie ist tatsächlich durch Mord der Welt abhandengekommen, während Mahler den Tod ganz anders beschreibt. Bei Haselhorn wird er fast zärtlich und von bewegender Natürlichkeit.

Borowicz untermalt das mit genauso viel Schönheit im Orchester. Da geht nichts verloren und man hört alles in schönstem Zusammenwirken.

This is a remarkable CD, not only because of Samuel Hasselhorn’s singing, which is outstanding as expected, but also because of the conductor Lukasz Borowicz. I have made it known in a long series of reviews that I hold him in high esteem. But the sound he produces in this program with the Poznan Philharmonic is phenomenal. In no other recording that I know of does so much happen in the orchestra in Mahler’s Revelge as you can hear in this recording. This is the whole Mahler theatre, the sonic cabinet of curiosities in full! But that’s not all: in Urlicht, the orchestra envelops the voice perfectly and, together with the instrumental parts, brings it to optimum effect, because the music is really complete. And Haselhorn’s voice is no less fascinating in this recital, his singing is dramatically gripping, with colourful and dynamic nuances and a concise presentation of the text. Revelge is not only dramatic with him, it is full of relentlessness, which makes the inner compulsion of the marching drastically audible, regardless of losses. Borowicz and the orchestra reinforce this thoughtless compulsion, which also makes the bones march in rank and file. Engelbert Humperdinck’s ‘Verdorben! Gestorben!’ from the opera Königskinder is no less gripping because Hasselhorn sings very sensitively and Borowicz makes the rhapsodic quality of the opulent orchestral accompaniment communicative and evocative.

Completely different sounds are offered to the listener in Pierrot’s Tanzlied from Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt, in which the charm and bitterness of Pierrot are ideally combined in Hasselhorn’s lyrical singing to make us empathize with the fate of this clown.

What follows in Mahler’s Midsummer Night’s Song is once again top-notch, as Borowicz places the voice in a luxury box with a wonderfully present and colorful orchestra. In comparison, Hampson and Bernstein sound almost pathetic and mannered.

Hasselhorn sings towards death in a very composed and almost positive and heroic way, without any lachrymose, surrounded by a colorful and grandiose orchestral sound, which has not often been heard in this rhetoric, neither with Karajan nor with Thielemann and Boulez: nowhere is the symbiosis of voice and orchestra as perfect as in this recording.

This is also true of the absolutely phenomenal and exciting Erlkönig setting of ‘Herr Oluf’. Mahler’s « Urlicht » sounds all the more moving in an interpretation marked by naturalness and honesty.

In Alexander von Zemlinsky’s Altem Garten everything blossoms in the extreme chromaticism of the music, and the fascinating orchestration with the beautifully interwoven vocal lines makes this song transcend into beauty, not least thanks to Hasselhorn’s imaginative and vocally magnificent performance.

There is great romanticism in Braunfels’ description of a soldier’s grave, which contrasts sharply with the surreal duet between Marie and Wozzeck in Berg’s opera. But Marie is actually lost to the world through murder, while Mahler describes death in a completely different way. With Haselhorn, it becomes almost tender and movingly natural.

Borowicz underpins this with just as much beauty in the orchestra. Nothing is lost and you can hear everything interacting beautifully.