Zunächst waren es größer besetzte Kammermusikwerke, in denen Brahms dem Cello schöne Kantilenen anvertraute, so im ersten Klaviertrio, dem ersten Streichsextett sowie auch noch in den beiden ersten Klavierquartetten. In ihrem tief melancholischen Charakter und mit ihren Trauerthemen wurde die Sonate dann exemplarisch für das Instrument.

Energiegeladen, aber auch nachdenklich, voller Stimmung und Empfindung präsentieren die Interpreten die Sonaten. Etwa im Allegro appassionato der zweiten Sonate, also deren drittem Satz, agieren sie auch kräftig drängend. Trotz aller Melancholie in der ersten Sonate schaffen sie es, dieses Stück mit hoffnungsvollem Charakter in Erinnerung zu halten. Umso mehr gilt dies für die zweite Sonate, die wie oft bei Brahms einen Gegensatz im Stimmungsbild bildet.

Mit seinem sonor zum Klingen gebrachten Instrument zeichnet Christian Poltéra trotz aller technischen Leichtigkeit eine typische charakterliche Cellostudie par excellence. Diese Version der Sonaten prononciert das scheinbar Teutonische des norddeutschen Komponisten allenfalls durch das dunkle Timbre und nicht durch knarzendes Spiel.

Pianist Ronald Brautigam agiert musikalisch im besten Einvernehmen mit dem Cellisten. Er spielt leicht und fein artikuliert. Mit selbstbewusstem Einsatz, das dem Cellisten aber nicht den Schneid abkauft, zeigt er sich als ebenso selbständiger wie auch aufmerksam auf die gemeinsame Schrittweite des Duos bedachter Partner. Das technisch makellose Spiel gründet auf einem perfekten Einvernehmen. Beiden gemeinsam ist auch das auf die finale Prägung hin ausgerichtete Denken, das bei Brahms nicht zu kurz kommen sollte.

Die fünf Stücke im Volkston von Schumann sind im Sinne der Schlichtheit des Ausdrucks, einem ‘Volkston’, der nach allgemein verständlicher Kunst suchte, gehalten. Poltéra und Brautigam erliegen aber nicht dem Fehler, diese Kleinodien abschätzig zu behandeln. Bei unaufmerksamem Zuhören mag man sie sogar für Sätze der Sonaten halten. Für Poltéra bieten sie nochmals einen Platz, die wunderbaren Kantilenen, wie sie nur einem Cello möglich sind, empfindungsvoll wirken zu lassen.

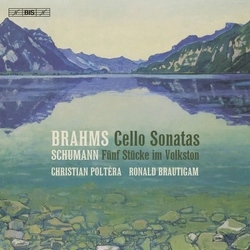

Initially, Brahms entrusted the cello with beautiful cantilenas in larger chamber works, such as the first Piano Trio, the first String Sextet, and the first two Piano Quartets. With its deeply melancholy character and sad themes, the sonata became a model for the instrument.

The performers present the sonatas full of energy, but also thoughtful, full of mood and emotion. In the Allegro appassionato of the second sonata, the third movement, for example, they are also vigorously urgent. Despite all the melancholy in the first sonata, they manage to keep this piece in the memory with a hopeful character. This is even more true of the second sonata, which, as is often the case with Brahms, offers a contrast in mood.

With his sonorous instrument, Christian Poltéra draws a typical cello study par excellence, full of character, despite all technical lightness. This version of the sonatas emphasizes the seemingly Teutonic character of the North German composer only through the dark timbre and not through creaking playing.

Pianist Ronald Brautigam is in perfect musical harmony with the cellist. His playing is light and finely articulated. With a self-confident commitment that does not take away from the cellist’s edge, he proves to be a partner who is both independent and attentive to the duo’s common stride. Their technically flawless playing is based on a perfect understanding. What they have in common is their focus on the final impression, which should not be neglected in Brahms.

Schumann’s Five Pieces in Folk Tone are in the spirit of simplicity of expression, a « folk tone » that sought a universally understandable art. But Poltéra and Brautigam do not make the mistake of treating these gems with disdain. An inattentive listener might even mistake them for movements from the sonatas. For Poltéra, they once again offer a place for the wonderful cantilenas that are only possible on the cello.