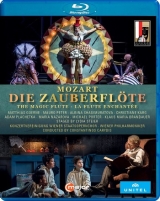

Die amerikanische Regisseurin Lydia Steier hatte eine gute Ausgangsidee: Sie ließ die Handlung der Zauberflöte durch einen Großvater erzählen (herausragend von Klaus Maria Brandauer gespielt) und eliminierte somit die oft gestelzt wirkenden Dialoge.

Doch wenn einmal die zweite Idee überhandnimmt, verblasst die erste auch schon. Nachdem Tamino sich per Bildnis in Pamina verliebt hat, muss er die ‘Geliebte’ in einem Zirkus suchen. Nicht, dass die Zauberflöte Fantasy nicht vertragen würde, aber hier ist es des Guten zu viel, so sehr sich Brandauers Zuhörer, die drei ständig präsenten Knaben – brillant interpretiert von drei Wiener Sängerknaben – auch bemühen, den roten Faden der Erzählung sichtbar zu halten.

Der Mozart- und Zauberflöten-Freund muss sich damit abfinden, dass Papageno ein Schlachtersohn ist und zunächst in einem blutverschmierten Metzgerkittel auftritt. Pamina ist eine Zirkusakrobatin, Tamino ein Soldat und Sarastro ein zigarrenrauchende Zirkusdirektor. Doch auch diese Idee landet auf der Müllhalde, wenn die letzte Prüfung Taminos und Paminas mit dem Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs zusammenfällt. Was es denn auch möglich macht, dass Sarastro die Drei Damen erschießen lässt und Monostatos und die Königin der Nacht selber erschießt.

Dass in dieser überfrachteten und hoffnungslos kontradiktorischen Szenerie das Visuelle dominiert und die Musik an den Rand gedrückt wird, ist eine leidige Begleiterscheinung einer Inszenierung, in der weniger definitiv mehr gewesen wäre.

Und die Musik: nun ja, vieles ist gut, aber keiner der Hauptprotagonisten kommt über solides Mittelmaß hinaus. Sehr gut spielen die Wiener Philharmoniker, und dem Dirigenten Constantinos Carydis gelingen auch immer wieder sehr stimmungsvolle Momente, vor allem in den Chorszenen. Musikalisch hat man jedoch weitaus bessere Zauberflöten-Aufführungen erlebt. Aber das ist wohl der Tribut, den die Salzburger Festspiele an eine Inszenierung zahlen müssen, die, wie so vieles in der heutigen Welt, mit Visuellem blenden soll und die Musik diesem Zwang so sehr unterordnet, dass die Sänger schauspielerisch zu viel zu tun haben und sogar gegen ihre musikalischen Charaktere wirken. Mozarts geniale Musik gerät dabei in den Hintergrund.

American stage director Lydia Steier had a good initial idea: she lets a grandfather tell the story of the Magic Flute (outstandingly played by Klaus Maria Brandauer) and thus eliminated the often stilted dialogues. But when a second idea comes in, the first one fades. After Tamino falls in love with Pamina via a portrait, he has to look for her in a circus. Not that the Magic Flute does not tolerate fantasy, but here it is simply too much, even though Brandauer’s listeners, the three constantly present boys – brilliantly played by three Wiener Sängerknaben – try to keep the golden thread of the story visible. We have to accept the fact that Papageno is the son of a slaughterer and first appears in a blood-stained butcher’s coat. Pamina is a circus acrobat, Tamino a soldier and Sarastro a cigar-smoking circus director. But even this idea is dumped when the last test of Tamino and Paminas coincides with the beginning of the First World War. For Steier this makes it possible for Sarastro to have the Three Ladies shot and to personally kill Monostatos and the Queen of the Night. So, the visual element dominates in this overloaded and hopelessly contradictory scenery of a production in which less would definitely have been more. And the music? Well, much is good, but none of the main protagonists goes beyond solid averageness. The Vienna Philharmonic plays very well, and the conductor Constantinos Carydis succeeds in creating some atmospheric moments, especially in the choir scenes. Musically, however, one has experienced far better Magic Flute performances. But this is probably the tribute that the Salzburg Festival has to pay to a production which, like so much in today’s world, is supposed to dazzle with visual effects and subordinates music to this compulsion so strongly that the singers have to give the priority to their acting and in some cases even work against their musical character. Mozart’s brilliant music fades into the background.